Why I don't do vaginal exams ~ Wisdom from a Traditional Birth Companion

I let my new client know what would happen when I arrived at her home when she was in labour. We talked about sanitation measures, spending time in the kitchen, setting up the pool, and where I could take a nap if she needed some privacy. I said I would not be doing any vaginal exams as I think they’re rude, and she wept with relief.

I specialise in trauma and the majority of my clients are refugees from the medical system, running from ritual abuse and routines that protect the industry. They want someone to mentor them through to a healthy birth without the traps and trappings of the industry that removed their choice, and violated their autonomy and their dignity.

As a traditional birth attendant, I don’t do vaginal exams.

I was talking with my new client about what would likely happen when I arrived at her home when she was in labour. We talked about sanitation measures, spending time in the kitchen, setting up the pool, and where I could take a nap if she needed some privacy. I said I would not be doing any vaginal exams as I think they’re rude, and she wept with relief.

I specialise in trauma and the majority of my clients are refugees from the medical system, running from ritual abuse and routines that protect the industry. They want someone to mentor them through to a healthy birth without the traps and trappings of the industry that removed their choice, and violated their autonomy and their dignity.

We won’t go into the history of obstetrics that began with the burning of witches (midwives and healers), the rise of the man-midwife, the development of lying-in hospitals, and eventually the wholesale co-opting and medicalisation of birth. Suffice it to say that obstetrics and hospitalisation didn’t “save” women and babies (1). It created untold harm and mortality until they learned better infection control and saner behaviours. Today, it’s still leaving a trail of destruction as about 1/3 of their clients are traumatised (2,3,4) and about 1 in 8 enter parenthood with postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder (5,6,7). Suicide is a leading cause of maternal death in the first year and is highly correlated to trauma (8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16). It’s an industry out of control with unjustifiable caesarean rates, dangerous inductions for spurious reasons, and wholesale overuse of medications and interventions.

What women didn’t notice in this process of medicalisation and co-opting of their physiology for profit is that the medical industry took ownership of their vaginas once they became pregnant. Pregnancy transfers ownership of the vagina from the woman to the industry. Midwifery and obstetrical regulations stipulate that inserting an instrument, hand, or finger beyond the labia majora is a restricted practice sanctioned by legislation (17). To test this, see how long it takes for someone in the industry to file a Cease and Desist or start a campaign of persecution for the purpose of prosecution if they catch wind of anyone but one of their own sticking their fingers up there. No one but an insider sticks their fingers into their territory. It doesn’t matter who the mother gives her permission and consent to - it must be a member of the priesthood of modern medicine.

Of course, in their benevolence, they’re generally quite accommodating where partners are concerned, because most partners are male and obstetrics is exceedingly misogynistic. They value the needs and the pleasures of the D.

As a traditional birth attendant, I don’t do vaginal exams. For one thing, it’s considered a restricted practice for just the medical pundits and not doing them with my clients keeps the industry players somewhat placated knowing I’m not intruding into their turf. But the real reason is because I think they’re completely unnecessary and wouldn’t do them even if the medical folks begged me to under the guise that it would make birth safer.

To better understand the offence of the routine vaginal exam, we have to go back in time to when the male-midwife moved into the sanctity of women-centred birth and the domain of the midwife. It was profitable. And they convinced the public that they would provide a superior service based on the cultural belief of the time that women were disadvantaged by an inferior intellect and a predilection for sorcery (18,19). They also brought with them the medical perspective that women were an error of nature and that the world, and thus its inhabitants, were but a machine that could be best understood by coming to know its parts in isolation of the whole.

And so began dissection, mechanisation, and reducing birthing women to their parts. She became a womb expelling a foetus through a vagina. Think of today’s obstetrical “power, passenger, passage” perspective on how birth unfolds. Not much has changed in 400 years.

By sticking their fingers up there, they discovered that the cervix opens to expel the foetus. Oh, happy day! From the morgue to the birth suite, physician fingers were poking everything. Throughout the early and mid 1800’s, the infection rate in some hospitals soared as high as 60% from the mysterious childbed fever, with death rates as high as 1 in 4 (20). Nothing the doctors did was contributing to this mystery as physicians were gentlemen and gentlemen didn’t carry germs (21). And once they did accept that their filthy practices were killing women, rather than abandon the idiocy of penetrating their patients in labour, they eventually figured out how to make it less dangerous.

The practice of obstetrics has always been highly resistant to change and common sense. After all, they’ve had 400 years to figure things out and women are still birthing on their backs!

Once it was discovered that the cervix dilates as part of the labouring process, the medical industry has been fixated on that bit of tissue and made it the focus of their entire assembly line drive-through everyone-gets-what’s-on-the-menu service. That bit of tissue determines how the ward allocates services, whether the client will be permitted to stay, and how long she’ll be allowed to use their services before the next client needs the bed.

Thanks to Dr. Emanuel Friedman, who examined the cervices of 500 sedated first-time mothers in the 1950’s and plotted their dilation on a graph and matched it to the time of their birth – we now have the infamous Friedman’s Curve and the partogram.

© Evidence Based Birth

The partogram is a graph that plots cervical dilation and descent of the foetal head against a time-line. When the graph indicates that progress is slower than is allowable according to the particular chart chosen by their institution, then the practitioner is called upon to administer various interventions to speed things up to keep the labour progressing well, aka, profitably. Should these acceleration measures fail to produce a baby in a timely manner or cause foetal distress, then a caesarean section is the solution. “Failure to progress”, and the accompanying foetal distress that is often a consequence of those acceleration measures, are the leading causes of a primary caesarean (22).

Obstetrical partogram

In addition to clearing the bed for the next client, obstetrics has another reason for expediting labour. The more vaginal exams a woman receives, the greater the likelihood she’ll develop a uterine infection (23). So, once they start the poking, they need to get the baby out before their prodding adds another problem for them to solve.

In the absence of a medical situation, routine vaginal exams in labour are for the purpose of charting in order to maintain a medicalised standard of modern technocratic birth.

A labouring client will not be admitted to a hospital without a vaginal exam to determine if her dilation is far enough along for their services (unless she’s clearly pushing). And this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Early admission to the hospital results in more interventions and more caesareans than later admission (24). This is a business and time is money.

A regulated midwife attending a homebirth will likewise perform a vaginal exam upon arrival at the client’s home to determine if the client is far enough along to warrant their limited resources and time by staying and beginning the partogram or leaving and waiting to be called back later. They must also follow the rules of the hospital at which they have privileges or their regulatory agency and transport for augmentation/acceleration if the partogram shows a significant variation.

All of this is predicated on the outdated and obsolete notion that women are machines and birth is a linear process. The only thing a vaginal exam reveals is where the cervix is sitting at that particular moment and how it’s interpreted by that particular practitioner. Women are not machines and birth is not linear. Just like any mammal, birth can be slowed, stopped, or sabotaged by an unfavourable environment or reckless attendants. I’ve said for years that it’s so easy to sabotage a good birth, it’s embarrassing.

“Years ago, I was with a first-time mother planning a family-centred homebirth. She was on the clock and had a deadline. At 42 weeks gestation, she had until midnight that night to produce a baby in order to have a midwife-attended homebirth. After that, she was expected to report to the hospital for a chemical induction. As her contractions built throughout the day, her preferred midwife arrived and labour was progressing well. She was enjoying the process and the camaraderie of her sisters-in-birth. Eventually, one of the vaginal exams revealed a cervical dilation of 8 cm, indicating it was time to call in the 2nd midwife. Only, it was a midwife that had routinely upset the mother throughout pregnancy with requests for various tests and talk of all the dangers of declining routine testing. Upon learning this midwife was coming to the birth, labour slowed.

Soon enough, the 2nd midwife arrived and assumed authority over the birth process and insisted on repeated vaginal exams for the purpose of staying within the parameters of the partogram. Her vaginal exams were excruciating, no doubt because she was trying to administer a non-consenting membrane stripping as an intervention to address the slowed and almost non-existent contractions. Eventually, an exam revealed a dilation of only 6 cm. After several more hours of “torture” (according to this mother’s recount) to keep labour going rather than just leaving the mother to rest and accepting that this labour had been hijacked and needed time to regroup and restart, dilation regressed to 4 cm and the mother eventually ended up acquiescing to a hospital transfer, and experienced an all-the-bells-and-whistles birth, trauma, and postpartum PTSD.

This mother’s subsequent birth a couple of years later didn’t include inviting midwives and unfolded as it was meant to. After a day of productive and progressing labour that was clearly evident without sticking fingers up her vagina, she eventually got tired and labour slowed and stopped. She went to bed and I went home. When she woke up, labour resumed and a baby emerged swiftly and joyously. As it turns out, for her, she has a baby after a good sleep with people she trusts.”

What about the routine vaginal exams in late pregnancy? Glad you asked!

Since they don’t have good predictive value, meaning they won’t diagnose when labour will begin, how long it will take, or whether the woman’s pelvis will accommodate that particular baby prior to labour, they have 2 functions.

The first is to plan and initiate your induction.

A cervical exam provides information that is measured against a Bishop Score. A Bishop Score provides a predictive assessment on whether an induction is likely to result in a vaginal birth or is more likely to result in a caesarean for “failure to progress”. A cervix that scores higher is more likely to respond to an induction whereas a lower score indicates a less favourable outcome (25). Further, a vaginal exam allows the practitioner to begin the induction process with a membrane stripping/stretch-and-sweep.

The second purpose for routine vaginal exams in pregnancy is to build in sexual submission. It reaffirms the power dynamic where someone who is not the woman’s intimate sexual partner is allowed to penetrate her genitals at will. It makes their job much simpler once she’s is in labour. She has been trained to accept this violation.

A vaginal exam during labour might rarely be indicated when there is a problem that requires more information. A vaginal exam can help determine if there’s a possible cord prolapse requiring immediate medical attention, or can asses the position and descent of the baby to help suggest strategies to encourage the baby to move into a better position. However, when a labour is spontaneous, meaning it hasn’t been induced by any mechanical, chemical, or “natural” means, the labour isn’t augmented with artificial rupture of membranes or synthetic oxytocin, and the labouring woman is untethered and free to move as her body indicates, complications are far less likely.

Throughout my 35 years in supporting birthing families, I can say that babies do indeed come safely and spontaneously out of vaginas when there’s no one sticking their fingers up there. And they tend to come more quickly. Routine vaginal exams don’t contribute to the safety of the mother/baby. However, they do add to the safety of the practitioner who is tasked with placating the technocratic gods who demand they follow protocols and keep the wheels of the business running on track.

My reasons for not doing vaginal exams, even if the the technocratic gods gave their blessing, include:

They’re rude

They’re unnecessary

They shift the locus of power from the birthing woman to the person with the gloves

They introduce the potential for infection

They interrupt labour and can sabotage a good birth

They often hurt

They can traumatise the cervix

They can traumatise the mother

They can impact the experience of the baby

There are so many simpler ways to determine how labour is progressing

I don’t practice medicine or midwifery or engage in its absurdities

I really am not that interested in other people’s vaginas

Let’s talk about when labour does veer from a normal physiological process.

When the power dynamic places the labouring and birthing mother in charge of the experience, it actually becomes a safer and simpler process. She is the one who is experiencing the labour and birth and is the one relaying information. Only she is in direct communication with her baby. She is the one who knows when labour has exceeded her resources and she needs medical help, pharmacologic pain relief, or the reassurance of the technocratic model.

Of course, not all births unfold simply. However, my experience over these many years is that when women are not expected to submit to exams for the purpose of charting and the subsequent limitations imposed by those charts, birth unfolds a lot more simply far more often.

Much love,

Mother Billie ❤️

Endnotes

Tew, Marjorie. Safer childbirth?: a critical history of maternity care. (2013). Springer.

Garthus-Niegel, S., von Soest, T., Vollrath, M. E., & Eberhard-Gran, M. (2013). The impact of subjective birth experiences on post-traumatic stress symptoms: a longitudinal study. Archives of women's mental health, 16(1), 1-10.

Creedy, D. K., Shochet, I. M., & Horsfall, J. (2000). Childbirth and the development of acute trauma symptoms: incidence and contributing factors. Birth, 27(2), 104-111.

Schwab, W., Marth, C., & Bergant, A. M. (2012). Post-traumatic stress disorder post partum. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde, 72(01), 56-63.

Montmasson, H., Bertrand, P., Perrotin, F., & El-Hage, W. (2012). Predictors of postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder in primiparous mothers. Journal de gynecologie, obstetrique et biologie de la reproduction, 41(6), 553-560.

Beck, C. T., Gable, R. K., Sakala, C., & Declercq, E. R. (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder in new mothers: Results from a two‐stage US National Survey. Birth, 38(3), 216-227.

Shaban, Z., Dolatian, M., Shams, J., Alavi-Majd, H., Mahmoodi, Z., & Sajjadi, H. (2013). Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following childbirth: prevalence and contributing factors. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 15(3), 177-182.

Oates, M. (2003). Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. British medical bulletin, 67(1), 219-229.

Oates, M. (2003). Suicide: the leading cause of maternal death. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 183(4), 279-281.

Cantwell, R., Clutton-Brock, T., Cooper, G., Dawson, A., Drife, J., Garrod, D., Harper, A., Hulbert, D., Lucas, S., McClure, J. and Millward-Sadler, H. (2011). Saving Mothers' Lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006-2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology, 118, 1-203.

Austin, M. P., Kildea, S., & Sullivan, E. (2007). Maternal mortality and psychiatric morbidity in the perinatal period: challenges and opportunities for prevention in the Australian setting. Medical Journal of Australia, 186(7), 364-367

Palladino, C. L., Singh, V., Campbell, J., Flynn, H., & Gold, K. (2011). Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Obstetrics and gynecology, 118(5), 1056.

Grigoriadis, S., Wilton, A.S., Kurdyak, P.A., Rhodes, A.E., VonderPorten, E.H., Levitt, A., Cheung, A. and Vigod, S.N. (2017). Perinatal suicide in Ontario, Canada: a 15-year population-based study. Cmaj, 189(34), E1085-E1092.

CEMD (Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths) (2001) Why Mothers Die 1997–1999. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

Sareen, J., Cox, B. J., Stein, M. B., Afifi, T. O., Fleet, C., & Asmundson, G. J. (2007). Physical and mental comorbidity, disability, and suicidal behavior associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in a large community sample. Psychosomatic medicine, 69(3), 242-248.

Hudenko, William, Homaifar, Beeta, and Wortzel, Hal. (July 2016). The Relationship Between PTSD and Suicide. PTSD: National Center for PTSD, U.S. Department of Veterans Affair.

Act, Ontario Midwifery. "SO 1991, c. 31." (1991).

Smith Adams, K. L. (1988). From 'the help of grave and modest women' to 'the care of men of sense': the transition from female midwifery to male obstetrics in early modern England. (Master’s thesis, Portland State University.

Burrows, E. G., & Wallace, M. (1998). Gotham: a history of New York City to 1898. Oxford University Press.

Semmelweis, I. (1983). Etiology, concept, and prophylaxis of childbed fever. Carter KC, ed. Madison, WI.

Halberg, F., Smith, H. N., Cornélissen, G., Delmore, P., Schwartzkopff, O., & International BIOCOS Group. (2000). Hurdles to asepsis, universal literacy and chronobiology-all to be overcome. Neuroendocrinology Letters, 21(2), 145-160.

Caughey, A. B., Cahill, A. G., Guise, J. M., Rouse, D. J., & American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2014). Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 210(3), 179-193.

Curtin, W. M., Katzman, P. J., Florescue, H., Metlay, L. A., & Ural, S. H. (2015). Intrapartum fever, epidural analgesia and histologic chorioamnionitis. Journal of Perinatology, 35(6), 396-400.

Kauffman, E., Souter, V. L., Katon, J. G., & Sitcov, K. (2016). Cervical dilation on admission in term spontaneous labor and maternal and newborn outcomes. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 127(3), 481-488.

Vrouenraets, F. P., Roumen, F. J., Dehing, C. J., Van den Akker, E. S., Aarts, M. J., & Scheve, E. J. (2005). Bishop score and risk of cesarean delivery after induction of labor in nulliparous women. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 105(4), 690-697.

The system isn’t broken - but its people are

One third of birthing parents has a traumatic birth.

“The system is broken.”

One in 8 new parents enters parenthood with postpartum PTSD from the experience.

“The system is broken.”

Depending on where you live, one third, one half, or almost everyone has a surgical birth.

“The system is broken.”

One in 6 women are abused during their births.

“The system is broken.”

If we say it enough, we might believe it. However, the “system” is decidedly NOT broken. It is doing exactly what it was set up to do by any means available to it.

One third of birthing parents has a traumatic birth.[i] [ii] [iii]

“The system is broken.”

One in 8 new parents enters parenthood with postpartum PTSD from the experience.[iv]

“The system is broken.”

Depending on where you live, one third, one half, or almost everyone has a surgical birth.[v]

“The system is broken.”

One in 6 women are abused during their births.[vi]

“The system is broken.”

If we say it enough, we might believe it. However, the “system” is decidedly NOT broken. It is doing exactly what it was set up to do by any means available to it.

The “system” is how we deliver maternity services. It began when male-midwives, those physicians who broke social etiquette, began attending women in birth. They were barbaric in means because they were sanctioned by the Catholic church to carry sharp instruments that women were forbidden to use. Male barber-surgeons, the Chamberlains, invented the forceps but kept their secret hidden for a century. A few centuries of witch hunts where midwives and female healers were persecuted and executed taught the public to shy away from learning these skills – if they were women. The collusion of religion and medicine ensured that men gained and maintained a monopoly over sick care and what women were allowed to do with their own bodies.[vii]

Eventually, through clever marketing, the male midwife became the preferred attendant as they were considered superior in intellect.[viii] [ix] Women were forbidden to attend universities, practice medicine, or serve in leadership in religions that ruled the western politic, thus unable to influence how women were treated in childbirth.[x]

Sure enough, these clever men discovered how much more profitable it was to bring birthing clients to them rather than going out to their homes.[xi] And so emerged the ‘lying-in’ hospital. The wholesale slaughter of women in these death traps was on par with the witch hunts of a few centuries prior. One in ten women died from puerperal fever, brought on by the unwashed hands of physicians who went from cadaver to the birthing vagina.[xii] Despite the protests of the offensive Semmelweis to wash their hands, ego and elitism prevented them from adopting this simple strategy for many more years thus ensuring the needless deaths of countless more women.[xiii]

Ignaz Semmelweis washing hands with chlorine-water, 1846

Once chloroform and other means of anesthesia were available for use in childbirth, the medical societies lobbied the government to grant them exclusive access. Not that they were any more qualified to use these powerful drugs than any other discipline, they merely had the ear of those in power who made these decisions.[xiv] Next followed the most effective smear campaign in all of history to drive midwives and alternative healing modalities out of business. [xv] [xvi] By the end of WW2 the campaign was almost complete. Next came effective lobbying to ensure governments were only favourable to their approach and the money, legislations, and endorsements flowed to hospital based technocratic birth where the obstetrician is royalty.

Even today, midwives around the world are persecuted and legislated out of business for offering client-centred care and serving women outside of hospitals.

Leaning heavily on Henry Ford’s conveyor belt system of turning out cars, optimisations and standardisations were implemented to cut costs, increase revenue, and turn the business of birth into a well-oiled machine.[xvii]

What we have is an effective system of profit for those industry players who set it up this way.

Of course, women are abused in birth! It’s an effective means of getting them to submit to a routine, one-size-fits-all, conveyor belt, in-and-out, profitable baby factory.

Even the current schedule of prenatal visits has no basis in science, evidence, or benefit. It was created by those same male-midwives who took a good thing and made it $tandard. Certainly, diagnosing and treating medical issues is an important healthcare strategy, whether pregnant or not. In light of the evidence that today’s current schedule and routines have not produced the promised results of healthier pregnancies or births, the industry recommended and implemented a strategy to convince the public that the process of pregnancy could not be trusted to stay normal without their surveillance.[xviii]

Now let’s talk about the people.

Some people enter this industry because it’s proven itself as a profitable endeavour. Obstetrics includes a great deal of power and control over a physiological process that in most cases would unfold quite simply without them. This appeals to some people. It’s a position of elitism and sits higher on the social hierarchy. There’s nothing to see there. Nothing to reach. Nothing to change.

And some enter this industry because they believe they have something valuable to offer during one of the most sacred and vulnerable times in a person’s life. They believe in the importance of how new humans are greeted into this world.

But because they have entered a highly successful system, they witness and sometimes participate in horrific abuses of mothers and babies. Some are broken by this and are the walking and working wounded, grappling with trauma, burnout, PTSD, and even suicidal ideation. Some survive and continue doing the best they can without the learned skillset of trauma-informed care that protects them and their clients. And some become part of the system of abuse and profit as their initial purpose is co-opted by internalised patriarchy and misogyny.

But what’s to be done with those who are broken and those who are merely surviving? The system doesn’t care if they burnout and leave. Players are easily replaced by new inductees at beginner salaries. It was never set up to take care of anyone. It was set up as a profitable means of co-opting physiology for profit based on fear and coercion.

“What we have is a medical system that is literally killing people through suicide.”

Break time. Nature and birth are not always kind. Women have always benefited from the companionship and knowledge of their midwives. And when events became problematic, skilled surgeons and expert paediatricians have brought hope and life where there was once only death. This post only speaks to the system of facility-based birth that currently exists within a patriarchal, misogynistic, and technocratic paradigm.

Back to the people.

‘Burnout’ consists of three features

Emotional exhaustion – feeling emotionally depleted from being overworked

Depersonalisation and cynicism – unfeeling towards patients and peers with often negative, callous, and detached responses

Reduced personal efficacy – a reduced sense of competence or achievement in one’s work

Burnout, compassion fatigue, and trauma are often intermingled in the academic literature so it’s hard to get a sense of the enormity of the issue. However, we do know this:

Physicians

Female physicians have higher rates of burnout and less work satisfaction than males[xxiii]

Physicians have the highest rate of suicide of any profession[xxiv]

General population - 12.3 per 100,000

Physicians -28 to 40 per 100,000

Equal numbers of male and female physicians complete a suicide

Midwives

Midwives around the world report rates of burnout from 20%[xxv] to 65%[xxvi]

One third of midwives have clinical PTSD[xxvii]

Witnessing abusive care of patients creates more severe PTSD[xxviii]

Nurses

35% of labour and delivery nurses have moderate to severe secondary traumatic stress[xxix]

Witnessing or participating in abusive births is a direct contributor to trauma

24% higher rate of suicide than those outside the profession[xxx]

Nurses and Midwives

Female 192% more likely to complete suicide than females in other occupations

8.2 per 100,000 vs 2.8 per 100.000

Male 52% more likely to complete suicide than males in other occupations

22.7 per 100,000 vs 14.9 per 100.000

Male 196% more likely to complete suicide than female colleagues

22.7 per 100,000 vs 8.2 per 100.000[xxxi]

Doulas

Half of doulas report burnout[xxxii] where traumatic incidences and witnessing the mistreatment of labouring clients were direct causes of burnout. Secondary trauma causes doulas to leave the profession early, especially in light of institutional hostility, low income, and routine abuses of their clients[xxxiii]

From the client’s perspective, the simple answer is to birth outside the system.[xxxiv] It’s a reasonable option – unless you’ve drunk the Kool Aid and feel these parents are a danger to their foetus and must be punished through disrespectful care[xxxv] and calls to Childrens Apprehension Services. If enough clients choose an alternative to the system, then simple economics will drive change to bring back the customers.

Birthing families are paying a steep price for system-driven birth. High rates of trauma, postpartum PTSD, postpartum depression and anxiety, relationship breakdowns, and postpartum suicide.[xxxvi] [xxxvii] [xxxviii] [xxxix] [xl] [xli] What we have is a medical system that is literally killing people through suicide.

So, what to do with the crippling loss of health and wellness in those professionals who chose to enter the system to support families in a humane and compassionate manner? Is it even possible to bring back those who have lost their way?

Because the system of institutionalised maternity services is predicated on a patriarchal and misogynistic paradigm of control and elitism, it will never take care of those who are on the front lines. We must learn to take care of ourselves and each other.

Many good and decent people entered into the system of technocratic birth services with all the requisite technical skills and a desire to make a difference in the lives of birthing families. What was missing from their education and skills development were those specific skills that would equip them to work in that environment without losing their soul, their identity, or their life.

Fortunately, the same research that identifies the many problems with this delivery system of services, also identifies the many solutions. For those that are on a journey out of trauma and professional burnout towards recovery and professional efficacy, there are proven strategies that can help walk you towards recovery and wholeness. You can learn

A research-based understanding of the causes and consequences of birth trauma in the birthing client and how to avoid participating

A thorough understanding of secondary and vicarious trauma and its effects in healthcare providers

How to build neurological, biological, psychological, social, cultural, and structural resilience

The positive impact of affective empathy and how to use it

How to employ a trauma-informed approach with clients and peers that improves clinical accuracy, client and professional well-being, and reduces burnout, medical mistakes, and litigation

A knowledge of therapeutic modalities that are specific to trauma

Recovery is possible for those who seek it. While the system runs perfectly as it was designed to, it’s also possible that with enough recovered, equipped, and healthy participants we might see some significant changes that actually helps it to live up to its marketing of “healthy baby healthy mother”. In time, it might even include “healthy professionals”.

I’ve got the science. I’ve got the experience. And I’ve got the tools to help. Let’s do this together.

Much love,

Mother Billie

Endnotes

[i] Garthus-Niegel, S., von Soest, T., Vollrath, M. E., & Eberhard-Gran, M. (2013). The impact of subjective birth experiences on post-traumatic stress symptoms: a longitudinal study. Archives of women's mental health, 16(1), 1-10.

[ii] Creedy, D. K., Shochet, I. M., & Horsfall, J. (2000). Childbirth and the development of acute trauma symptoms: incidence and contributing factors. Birth, 27(2), 104-111.

[iii] Schwab, W., Marth, C., & Bergant, A. M. (2012). Post-traumatic stress disorder post partum. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde, 72(01), 56-63.

[iv] Montmasson, H., Bertrand, P., Perrotin, F., & El-Hage, W. (2012). Predictors of postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder in primiparous mothers. Journal de gynecologie, obstetrique et biologie de la reproduction, 41(6), 553-560.

[v] Boerma, T., Ronsmans, C., Melesse, D. Y., Barros, A. J., Barros, F. C., Juan, L., ... & Neto, D. D. L. R. (2018). Global epidemiology of use of and disparities in caesarean sections. The Lancet, 392(10155), 1341-1348.

[vi] Vedam, S., Stoll, K., Taiwo, T. K., Rubashkin, N., Cheyney, M., Strauss, N., ... & Schummers, L. (2019). The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reproductive health, 16(1), 77.

[vii] Ehrenreich, B., & English, D. (2010). Witches, midwives, & nurses: A history of women healers. The Feminist Press at CUNY.

[viii] Smith Adams, K. L. (1988). From 'the help of grave and modest women' to 'the care of men of sense': the transition from female midwifery to male obstetrics in early modern England. (Master’s thesis, Portland State University.

[ix] Burrows, E. G., & Wallace, M. (1998). Gotham: a history of New York City to 1898. Oxford University Press.

[x] Minkowski, W. L. (1992). Women healers of the middle ages: selected aspects of their history. American journal of public health, 82(2), 288-295.

[xi] Tew, M. (2013). Safer childbirth?: a critical history of maternity care. Springer.

[xii] Loudon, I. (2000). The tragedy of childbed fever. New York, Oxford University Press.

[xiii] Tew, M. 2013, op. cit.

[xiv] Bonner, T. N. (1989). Abraham Flexner as critic of British and Continental medical education. Medical history, 33(4), 472-479.

[xv] Getzendanner, S. (1988). Permanent injunction order against AMA. JAMA, 259(1), 81-82.

[xvi] Weeks, John. (n.d.). “AMA ‘Thwarts’ Other Professions Practice Expansion and a Challenge to CAM-IM Fields”. The Integrator Blog. http://theintegratorblog.com/?option=com_content&task=view&id=73&Itemid=1

[xvii] Perkins, B. B. (2004). The medical delivery business: Health reform, childbirth, and the economic order. Rutgers University Press.

[xviii] Ball, J. (1993). The Winterton report: difficulties of implementation. British Journal of Midwifery, 1(4), 183-185.

[xix] Peckham, C. (2016). Medscape lifestyle report 2016: bias and burnout. New York, NY: Medscape.

[xx] Avery, Granger, M.D., (2017). The role of the CMA in physician health and wellness. Canadian Medical Association.

[xxi] Imo, U. O. (2017). Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among doctors in the UK: a systematic literature review of prevalence and associated factors. BJPsych bulletin, 41(4), 197-204.

[xxii] Wu, F., Ireland, M., Hafekost, K., & Lawrence, D. (2013). National mental health survey of doctors and medical students.

[xxiii] Peckham, C., 2016, op. cit.

[xxiv] T’Sarumi, O., Ashraf, A., & Tanwar, D. (2018). Physician suicide: a silent epidemic. Reunión Anual de la American Psychiatric Association (APA). Nueva York, Estados Unidos, 1-227.

[xxv] Henriksen, L., & Lukasse, M. (2016). Burnout among Norwegian midwives and the contribution of personal and work-related factors: a cross-sectional study. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 9, 42-47.

[xxvi] Creedy, D. K., Sidebotham, M., Gamble, J., Pallant, J., & Fenwick, J. (2017). Prevalence of burnout, depression, anxiety and stress in Australian midwives: a cross-sectional survey. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 17(1), 13.

[xxvii] Sheen, K., Spiby, H., & Slade, P. (2015). Exposure to traumatic perinatal experiences and posttraumatic stress symptoms in midwives: prevalence and association with burnout. International journal of nursing studies, 52(2), 578-587.

[xxviii] Leinweber, J., Creedy, D. K., Rowe, H., & Gamble, J. (2017). Responses to birth trauma and prevalence of posttraumatic stress among Australian midwives. Women and birth, 30(1), 40-45.

[xxix] Beck, C. T., & Gable, R. K. (2012). A mixed methods study of secondary traumatic stress in labor and delivery nurses. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 41(6), 747-760.

[xxx] Office for National Statistics. (2017). Suicide by occupation, England: 2011 to 2015.

[xxxi] Milner, A.J., Maheen, H., Bismark, M.M., & Spittal, M.J. (2016) Suicide by health professionals: a retrospective mortality study in Australia, 2001–2012. Medical Journal of Australia 205 (6): 260-265.

[xxxii] Naiman-Sessions, M., Henley, M. M., & Roth, L. M. (2017). Bearing the burden of care: emotional burnout among maternity support workers. In Health and Health Care Concerns Among Women and Racial and Ethnic Minorities (pp. 99-125). Emerald Publishing Limited.

[xxxiii] Roth, L. M., Heidbreder, N., Henley, M. M., Marek, M., Naiman-Sessions, M., Torres, J. M., & Morton, C. H. (2014). Maternity support survey: A report on the cross-national survey of doulas, childbirth educators and labor and delivery nurses in the United States and Canada.

[xxxiv] Holten, L., & de Miranda, E. (2016). Women׳ s motivations for having unassisted childbirth or high-risk homebirth: An exploration of the literature on ‘birthing outside the system’. Midwifery, 38, 55-62.

[xxxv] Vedam, S., Stoll, K., Rubashkin, N., Martin, K., Miller-Vedam, Z., Hayes-Klein, H., & Jolicoeur, G. (2017). The Mothers on Respect (MOR) index: measuring quality, safety, and human rights in childbirth. SSM-Population Health, 3, 201-210.

[xxxvi] Oates, M. (2003). Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. British medical bulletin, 67(1), 219-229.

[xxxvii] Oates, M. (2003). Suicide: the leading cause of maternal death. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 183(4), 279-281.

[xxxviii] Lewis, G. (2007). Saving mothers' lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer 2003-2005: the seventh report of the confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. CEMACH.

[xxxix] Austin, M. P., Kildea, S., & Sullivan, E. (2007). Maternal mortality and psychiatric morbidity in the perinatal period: challenges and opportunities for prevention in the Australian setting. Medical Journal of Australia, 186(7), 364-367.

[xl] Palladino, C. L., Singh, V., Campbell, J., Flynn, H., & Gold, K. (2011). Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Obstetrics and gynecology, 118(5), 1056.

[xli] Grigoriadis, S., Wilton, A. S., Kurdyak, P. A., Rhodes, A. E., VonderPorten, E. H., Levitt, A., ... & Vigod, S. N. (2017). Perinatal suicide in Ontario, Canada: a 15-year population-based study. Cmaj, 189(34), E1085-E1092.

Birth Hijacked – The Ritual Membrane Sweep

I’ve written about many topics over the years but nothing has ever generated as much discussion, opposition, and vitriol as challenging the cherished routine membrane sweep/stripping, aka stretch-and-sweep. A few years ago, I wrote a post about how I’d like to see the routine, prior-to-40-weeks, without-medical-indication membrane sweep banned from obstetrical and midwifery practice. I talked about its risks and the fact that the clients I worked with called it a sexual assault when done without consent

The post went viral and I received hate messages and emails from around the world defending this procedure. In general, the sentiment was that I should most definitely be having sexual relations with myself, after which, I should be locked up and forever silenced. I also heard from hundreds of women whose births were ruined by days of painful, non-progressing contractions triggered by a membrane sweep that ended up in a fully medicalised all-the-interventions arrival for their baby that they didn’t want. And horrifically, even more hundreds wrote to share their stories of non-consenting, painful, and violating membrane sweeping when there was no reason for it, aside from the care provider’s decision that they had agency over their patient’s vagina and could do what they wanted when they wanted.

So what is it about membrane sweeping that is so cherished that challenging it generates death threats?

Buckle up. Here we go again!

©Hanna-Barbera

I’ve written about many topics over the years but nothing has ever generated as much discussion, opposition, and vitriol as challenging the cherished routine membrane sweep/stripping, aka stretch-and-sweep.

A few years ago, I wrote a post about how I’d like to see the routine, prior-to-40-weeks, without-medical-indication membrane sweep banned from obstetrical and midwifery practice. I talked about its risks and the fact that the clients I worked with called it a sexual assault when done without consent

The post went viral and I received hate messages and emails from around the world defending this procedure. In general, the sentiment was that I should most definitely be having sexual relations with myself, after which, I should be locked up and forever silenced. I also heard from hundreds of women whose births were ruined by days of painful, non-progressing contractions triggered by a membrane sweep that ended up in a fully medicalised all-the-interventions arrival for their baby that they didn’t want. And horrifically, even more hundreds wrote to share their stories of non-consenting, painful, and violating membrane sweeping when there was no reason for it, aside from the care provider’s decision that they had agency over their patient’s vagina and could do what they wanted when they wanted.

That particular post was prompted by a brief encounter with a new mother. Her baby was little and we got talking. She told me how she went to her usual prenatal visit at 36 weeks and the doctor said it was time for a vaginal check to see how things were coming along. She thought that was an ok idea and stripped accordingly, lay down on the examining table and put her feet in the stirrups. However, rather than a simple vaginal exam, she experienced excruciating pain that had her crawling up the table trying to escape that probing hand. The doctor removed her bloodied glove and when this woman asked why she was bleeding, the doctor responded, “That should get things going”. This mother had experienced a non-consenting, unplanned, and unknowing stretch-and-sweep to start labour before she or the baby were ready. She went home bleeding and cramping and within a few days went into labour and birthed a baby that was not ready to breathe. The baby spent 3 days in the NICU and she was devastated. Her birth was hijacked by a damnable routine from someone who should have known better or at least given a damn.

Yes, that was obstetrical violence. However, the routine of membrane sweeping for the mere reason that the client is at term is a deeply embedded ritual in obstetrics and mimicked by some midwives. I don’t think there is one other procedure that so callously turns a normally progressing pregnancy into a pathological event than this heinous routine.

So what is it about membrane sweeping that is so cherished that challenging it generates death threats?

Routines are habits that help organise our days

Let’s begin with some clarity on what I’m challenging.

First and foremost, I am not challenging the right for a pregnant person to choose a membrane sweep as a means of expediting labour. I fully support an individual’s right and autonomy to choose what is best for them.

Secondly, I am not challenging this as a tool for expediting labour when there is a medical indication.

I am challenging the ROUTINE of membrane sweeping that is done by some care providers as part of their normal and usual prenatal “package”, without any hint that there is a reason to expedite the birth of the baby due to an emerging medical condition.

At your cervix, ma’am

Let’s take a tour of the cervix. The cervix is a narrow passage that sits at the lower end of the uterus extending into the vagina. The cervix changes throughout the menstrual cycle and serves an important function in fertility. During ovulation, the cervix produces sperm-friendly mucus and becomes softer and more open to facilitate sperm reaching the ovum. When not ovulating, it produces sperm-unfriendly mucus and makes it more difficult for sperm to pass through to the uterus.

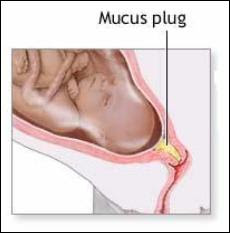

In pregnancy, the cervix fills with mucus, which creates a barrier to help prevent infection from passing through to the uterus. The cervix remains closed and rigid (like the tip of your nose) and is about 3-5 cm. long.

At term, in preparation for birth, the cervix will soften (like the inside of your cheek) due to the action of various hormones. The cervix is comprised of about 5-10% smooth muscle cells, which ensures it will stay closed and rigid throughout pregnancy. In preparation for labour, these muscle cells experience a programmed cellular death, which allows for the cervix to open (Leppert, 1995). The cervix will develop more oxytocin and prostaglandin receptors to help with the dilation process (Buckley, 2015). Prostaglandins, which are found abundantly in semen, ripens the cervix, digests the mucus plug, and promotes softening and shortening of the cervix.

Medical providers tend to give a great deal of attention to the cervix both prior to labour and in labour. It can provide some information that the medical folks find useful.

At term (around 40 weeks), the cervix can be felt to determine if it is ripening. Ripening means that the cervix is becoming softer, shorter, and is moving its position slightly forward. If so, it means that normal end-of-pregnancy hormones are doing their job. If not, it means that normal end-of-pregnancy hormones are doing their job, but they just haven’t gotten around to softening and shortening the cervix at the moment that a gloved hand is probing it.

This information is useful for planning an induction. A cervix that is shorter than 1.5 cm. is more predictive of spontaneous labour within the next 7-10 days than a longer cervix (Rao, Celik, Poggi, Poon, & Nicolaides, 2008). And a cervix that scores higher on the Bishop score is more predictive of an induction resulting in a vaginal birth rather than surgery (usually called “failure to progress”) (King, Pilliod, & Little, 2010). So that end-of pregnancy vaginal exam is about gathering information to plan your induction.

The other possibility for these routine (without medical indication) vaginal examinations in a healthy pregnancy is to develop submission and compliance in the client as she subjugates herself to the clinician by having her genitals penetrated by someone who is not her intimate partner.

Not too long ago, I was working with a postpartum client who was recovering from her birth experience. As a survivor of sexual assault she did not want anyone penetrating her genitals when she was labouring and giving birth and repeatedly told her midwife this. However, her midwife felt it was best for her to submit to vaginal exams in pregnancy to “get used to” them before she was in labour. Apparently, it never occurred to either of them that vaginal exams are optional and largely unnecessary for birthing a baby. In this case, the prenatal vaginal exams were for the purpose of building in submission and compliance so that the care providers could exercise agency over her body in labour.

Inductions: getting the baby out before it’s ready

An induction starts labour artificially before optimal hormonal physiology has prepared the baby and the mother for spontaneous birth. About 1 in 4 births begin by induction (BORN, 2013; Osterman & Martin, 2014). Although, there has been a slight decrease in inductions in recent years as fewer early-term inductions, meaning prior to 39 weeks, are performed. This has allowed more mothers to go into spontaneous labour without any additional adverse outcomes (Osterman & Martin, 2014). The cervix is one small part of the whole physiological process and since it can be reached easily by probing hands, it can provide a bit of information on whether an induction is likely to lead to a vaginal birth or is more likely to result in caesarean surgery.

There are lots of ways to artificially start labour before the mother or baby are ready. There are the so-called “natural” inductions:

Acupuncture and acupressure

Herbs and Homeopathy

Castor oil

Massage

Nipple stimulation

There are chemical inductions, which the literature calls “formal” inductions, as they require medical supervision:

Cervical ripening with prostaglandins

Intravenous synthetic oxytocin

And we have mechanical inductions, which also generally require medical supervision:

Artificial rupture of membranes aka “breaking the water”

Cervical ripening with a balloon catheter

Manual membrane sweeping/stripping, “stretch and sweep”

Ideally, an induction should only be suggested when the risks of staying pregnant outweigh the long and short-term risks of an induction. Depending on the method of induction those risks can include preterm birth, breathing problems in the baby, infection in the mother or baby, uterine hyper-stimulation, uterine rupture, fetal distress, breastfeeding failure, and rarely, death of either the mother or the baby.

Unfortunately, most inductions are done where the research affirms that the risks of an induction outweigh the risks of staying pregnant, including pre-labour rupture of membranes, gestational diabetes, suspected big baby, low fluid at term, isolated hypertension at term, twins, being “due”, or being “overdue” (Mozurkewich, Chilimigras, Koepke, Keeton, & King, 2009; Cohain, n.d.; Mandruzzato et al., 2010).

“membrane sweeping is a procedure meant to induce labour so that the client won’t be induced later”

Membrane sweeping: Fred Flintstone manipulating your physiology

Membrane sweeping involves the provider inserting their gloved hand into a mother’s vagina and manually stretching open the cervix and then running their finger around the opening of the cervix to separate the amniotic sack from the lower uterine segment. Caregivers will say it feels much like separating Velcro.

This procedure has the potential to trigger labour because it releases extra prostaglandins at the cervix. If the membrane sweep results in a shorter cervix, then it doesn’t make any difference in whether the mother is subsequently induced, but it does decrease the incidence of c-section. However, membrane sweeping is much more likely to result in cervical lengthening – which is predictive of NOT going into labour (Tan, Khine, Sabdin, Vallikkannu, & Sulaiman, 2011).

Prostaglandins are one of many important hormones that are needed for labour and birth. As pregnancy progresses and it’s getting time for the baby to be born, there are complex processes that prepare and protect the baby and are necessary for labour to commence. For example, the cervix and the uterus develop prostaglandin receptors so that necessary prostaglandins have a place to “land” or “connect” so that they can do their job. The uterus develops an abundance of oxytocin receptors so that this love hormone that is produced in the brain can connect with the uterus and cause contractions. The baby’s brain develops oxytocin receptors, which is neuro-protective for the journey ahead. There is an increase in estrogen, which activates the uterus for delivery. There are inflammatory processes within the uterus that help to mature the baby’s lungs to prepare for breathing on the outside. The baby’s brain develops increased epinephrine receptors to protect it from any gaps in oxygen during the birth. The mother’s brain develops endorphin receptors for natural pain relief. And there is an increase in prolactin to prepare the mother for breastfeeding and bonding. (Buckley, 2015)

When considering the finely-tuned and delicate interplay of complex and specific processes that brings the baby earth-side, a manual stretch-and-sweep at term without any medical indication is like getting Fred Flintstone to program an app that regulates the autonomic nervous system. It’s a crude, blunt instrument inserted into a complex system with the intention of bypassing evolutionarily necessary adaptive processes to cut the pregnancy short by a possible few days.

Let’s try to induce labour so we don’t have to induce labour

A Cochrane Review (Bouvain, Stan, & Irion, 2005) evaluated available studies comparing membrane sweeping to no sweeping. In general, this procedure can reduce the duration of pregnancy by up to three days. However, the authors noted that only small studies showed this reduction in pregnancy duration whereas larger studies didn’t, suggesting some bias. Because membrane sweeping doesn’t usually lead to immediate labour, it is not recommended when the need to get the baby out is urgent. Its primary use is to “prevent” a longer gestation and therefore an induction by more risky means.

A stretch-and-sweep is a procedure that is meant to induce labour so that you won’t be induced later. The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada wrote in their 2013 Practice Guideline, which was reaffirmed in 2015, that “routine sweeping (stripping) of membranes promotes the onset of labour and that this simple technique decreases induction rates.”

Again: membrane sweeping is a procedure meant to induce labour so that the client won’t be induced later.

It assumes that the later induction is non-negotiable and the client’s best hope is that this early induction “saves” her from the risks of the later induction.

This is no different than all those “natural” inductions that are employed when trying to induce labour so the mother doesn’t have experience an induction – or the challenge of just declining the planned induction. It takes the approach that planned inductions are non-negotiable. Of course, mothers may chose a natural induction as a means of expediting the births of their babies for a number of reasons and I fully support their autonomy and choice to do so.

If there is a medical need to get the baby out to preserve its or its mothers life, then this dyad should be under medical supervision and receiving the best medical care possible. We need to critically evaluate the mentality that says, “let’s try to induce so we don’t have to induce”.

We’ve bought into a culture where non-evidence-based time limits and spurious reasons are given for booking inductions that don’t line up with the science. Rather than supporting mothers in exploring the science, doing a targeted risk/benefit analysis based on her particular situation, and supporting the mother in informed decision making, we line up the early inductions hoping to out-smart, out-wit, and out-play the medical providers who routinely induce based on outdated information or habit or hospital protocols that are based in their insurance risk-management strategy.

If this procedure is not recommended when there is an urgent need to get the baby out (Bouvain et al., 2005) and its primary purpose is to prevent a later induction where the indication is a pregnancy continuing beyond the cut-off date of the caregiver or institution (SOGC, 2013), then it has no medical indication.

What else did the Cochrane Review find?

There was a high level of bias in many of the studies, in part, because there could be no blinding. The clinicians knew they were performing the procedure and the clients knew they’d received it due to discomfort and pain

It was an out-patient procedure meaning there was no urgent reason for the induction

It did not generally lead to labour within 24 hours

No difference in oxytocin augmentation, use of epidural, instrumental delivery, caesarean delivery, meconium staining, admission to the NICU, or Apgar score less than seven at five minutes between sweeping and non-sweeping. This means it didn’t show any benefit

No difference in pre-labour rupture of membranes, maternal infection or neonatal infection. However, it’s worth noting that the non-sweeping participants were subject to routine obstetrical services that includes many vaginal exams that increase pre-labour rupture of membranes and infection (Maharaj, 2007; Zanella et al., 2010; Lenihan, 1984; Critchfield et al., 2013)

Significant pain in the mother during the procedure

Vaginal bleeding after the procedure

Painful contractions for the next 24 hours not leading to labour

What we have here is a routine that hurts the mother and has no significant benefit – aside from maybe possibly putting her into labour before another planned induction.

As the Cochrane Review discovered, the likely outcome of a membrane sweep is painful non-progressing contractions. This is often mis-interpreted as “labour” and the client is sent to the hospital for an induction anyway because she’s been “in labour” for 24-48 hours without progress. This is the epitome of a hijacked birth that turns a normal physiological process into a pathological one leading to the cascade of interventions, sometimes all the way up to an unwanted and unplanned caesarean for “failure to progress”. To convert the natural process into a pathological one is part of the classic definition of obstetrical violence (D'Gregorio, 2010).

They call it ‘birth rape’

For those who experienced this without their prior knowledge or consent, their comments overwhelmingly spoke of rape. This was especially pronounced in those with a history of prior rape. Studies confirm that those with a history of rape experience the routines of industrial birth differently than those without a history of sexual assault. For survivors, procedures that are uneventful for others can inadvertently put them “back in the rape” (Halvorsen, Nerum, Øian, & Sørlie, 2013).

Frankly, it’s unconscionable that any care provider would brazenly take the opportunity to manually manipulate a woman’s cervix, knowing it introduces risks and has the potential to hurt her, without the express knowledge and consent of the client following an informed choice discussion.

While membrane sweeping is intended to induce labour, it’s also used on labouring women to hurry things along. During labour, the cervix is being moved and thinned by the action of uterine muscles contracting and pulling the cervix up and around the baby’s head. The cervix is working hard and it’s tender. Many women will report that they screamed, cried ‘no’, tried to kick the provider’s hand away, or tried to crawl up the bed to get away from the invasive exam.

I remember one dark cold February night, years ago, when I was called to be with a family in labour. There was an ice storm and my trip there was dangerous and precarious. Eventually, my car slid into their street and managed to stop somewhere close to the driveway. I quietly entered the house to hear a mother in the throes of glorious, deep, active labour. I knew it wouldn’t be long before the baby arrived. I announced myself and tiptoed upstairs to see her on hands and knees with more blood than I would have expected on the towel beneath her. She said she invited her midwife to the birth and expected her to be there any minute. Soon enough, a beautiful baby boy gently emerged and landed safely into his daddy’s waiting hands. By the time the midwives arrived, the new family was tucked into bed enjoying a post-birth snack and cup of tea.

As the new family was bonding, I joined the midwives downstairs who were making notes in their client’s medical charts to make them some tea and offer a snack. I overheard one midwife say, “Oh yeah, when I was here earlier, she was about 6cm so I did a stretch-and-sweep”.

“Oh yeah.

Now I remember.

She was in active labour so I did an invasive and painful procedure to speed things up during a dark and dangerous ice storm.

Without her knowing I would do that.”

This is nothing but reckless cruelty. Yet this kind of cruelty permeates maternity services where women are routinely hurt for the sole purpose of interfering in their physiology and the safety of the birth process in order to get the baby out before they do even more risky and dangerous things.

And that is why I would like to see the ROUTINE, WITHOUT MEDICAL INDICATION membrane sweep removed from obstetrical and midwifery practice. It shouldn’t be the luck of the draw that a pregnant client gets one of the “good ones” who only induces a client when there is a medical need, with an informed choice discussion, and full consent.

To return to my original question: what is it about membrane sweeping that is so cherished that challenging it generates death threats?

It’s a deeply embedded ritual in a toxic medical culture that presumes to take authority over a pregnant woman’s sexual organs for the purpose of dominating the physiological process and then becoming a hero to the interrupted physiology and complications that ensue. It’s about power and control. And challenging this is a dangerous act of sedition. Those who do this to their clients like being the hero and clients who defend this need to believe they were saved from something – otherwise the truth is just too awful.

Make wise choices.

Much love,

Mother Billie

#endobstetricalnonsense #informedconsent #obstetricalviolence #membranesweeping #stretchandsweep #withoutconsent #birthrape #failuretoprogress

References

Better Outcomes Registry Network. (BORN). 2013. Provincial Overview of Perinatal Health in 2011–2012.

Boulvain, M., Stan, C. M., & Irion, O. (2005). Membrane sweeping for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1).

Buckley, S. J. (2015). Hormonal physiology of childbearing: Evidence and implications for women, babies, and maternity care. Washington, DC: Childbirth Connection Programs, National Partnership for Women & Families.

Cohain, J. S. Reducing Inductions: Lack of Justification to Induce for “Postdates”.

Critchfield, A. S., Yao, G., Jaishankar, A., Friedlander, R. S., Lieleg, O., Doyle, P. S., ... & Ribbeck, K. (2013). Cervical mucus properties stratify risk for preterm birth. PloS one, 8(8), e69528.

D'Gregorio, R. P. (2010). Obstetric violence: a new legal term introduced in Venezuela.

Halvorsen, L., Nerum, H., Øian, P., & Sørlie, T. (2013). Giving birth with rape in one's past: a qualitative study. Birth, 40(3), 182-191.

King, V., Pilliod, R., & Little, A. (2010). Rapid review: Elective induction of labor. Portland: Center for Evidence-based Policy.

Lenihan, J. J. (1984). Relationship of antepartum pelvic examinations to premature rupture of the membranes. Obstetrics and gynecology, 63(1), 33-37.

Leppert, P. C. (1995). Anatomy and physiology of cervical ripening. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology, 38(2), 267-279.

Maharaj, D. (2007). Puerperal pyrexia: a review. Part II. Obstetrical & gynecological survey, 62(6), 400-406.

Mandruzzato, G., Alfirevic, Z., Chervenak, F., Gruenebaum, A., Heimstad, R., Heinonen, S., ... & Thilaganathan, B. (2010). Guidelines for the management of postterm pregnancy. Journal of perinatal medicine, 38(2), 111-119.

Mozurkewich, E., Chilimigras, J., Koepke, E., Keeton, K., & King, V. J. (2009). Indications for induction of labour: a best‐evidence review. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 116(5), 626-636.

Osterman, M. J., & Martin, J. A. (2014). Recent declines in induction of labor by gestational age.

Rao, A., Celik, E., Poggi, S., Poon, L., & Nicolaides, K. H. (2008). Cervical length and maternal factors in expectantly managed prolonged pregnancy: prediction of onset of labor and mode of delivery. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology: The Official Journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 32(5), 646-65.

Rayburn, W. F., & Zhang, J. (2002). Rising rates of labor induction: present concerns and future strategies. Obstetrics & gynecology, 100(1), 164-167.

Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. SOGC. 2013. Clinical Practice Guideline, No. 296, Indution of Labour.

Tan, P. C., Khine, P. P., Sabdin, N. H., Vallikkannu, N., & Sulaiman, S. (2011). Effect of membrane sweeping on cervical length by transvaginal ultrasonography and impact of cervical shortening on cesarean delivery. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, 30(2), 227-233.

Zanella, P., Bogana, G., Ciullo, R., Zambon, A., Serena, A., & Albertin, M. A. (2010). Chorioamnionitis in the delivery room. Minerva pediatrica, 62(3 Suppl 1), 151-153.

On the Art of Discussing Paradigm-Shifting Topics

Everyone has an intellectual/mental/emotional operating system – a personal paradigm that serves as a frame of reference containing basic assumptions and ways of thinking. This personal paradigm is the means by which we make sense of the world around us. It helps us to filter, understand, and categorise information and experiences. It helps us to know what is “true” and what isn’t; it guides our responses and our actions.

Humans are designed to be in connection with each other. We operate mostly unconsciously through hormones, synapses, and other magical pathways. Our primary operating system is our para-sympathetic nervous system – our “calm and connected” system. This part of our autonomic nervous system keeps our hearts beating, our lungs breathing, and our food digesting. The main hormone of this system is oxytocin – the hormone of love, trust, bonding, and connection. This is why isolation is so effective at crushing and changing people, and why friends and loved ones can heal and nurture new ideas.

Personal paradigms, once settled and serving us reasonably well are most likely to be changed by 2 things: Great Suffering or Great Love.

Everyone has an intellectual/mental/emotional operating system – a personal paradigm that serves as a frame of reference containing basic assumptions and ways of thinking. This personal paradigm is the means by which we make sense of the world around us. It helps us to filter, understand, and categorise information and experiences. It helps us to know what is “true” and what isn’t; it guides our responses and our actions.

Source: Paradigm Dramas in American Studies: A Cultural and Institutional History of the Movement. Gene Wise American Quarterly, Volume 31:3 (1979): 293-337.

For someone who was raised on the streets, relying on street-smarts and their wits, they may understand the world to be a hostile place with scarce resources and easily manipulated marks. This guides their responses and their actions. However, someone raised in a loving home with abundance and gentle guidance may understand the world to be an accommodating place where hard work and relationships lead to prosperity and contentment.

A personal paradigm develops over one’s lifetime and depends on many things,

One’s macro-culture – that’s the big stuff, like country of origin, current community, heritage, race, and cultural history

One’s micro-culture – that’s the smaller stuff, like family of origin, friends, current family members, or caregivers

Education – this includes the schools one attended, what was learnt, whether they felt successful in their education, and how the individual has continued to educate themselves, including interacting with mentors

Personal experiences – this is the stuff one has experienced in their lifetime and what it’s taught them about themselves, others, and the world around them

Media – the movies that are viewed, the stories read, the news that’s told, the images shown, the podcasts listened to, and the pages and the people followed

This is how we make sense of the world.

When someone is told that they are part of the privileged, they’re going to evaluate that against their personal paradigm, in particular, their personal experiences. They’ll be thinking of whether they were sent to school or educated. Whether they had enough food each day or a safe home to live in. Whether they were beat up or molested in childhood or how many important people in their life died. Or how many times they’ve been sexually assaulted. They may not feel particularly privileged.

Likewise, an individual whose life is filled with opportunity and meaningful relationships may not feel marginalised, despite sharing some characteristics or heritage with traditionally marginalised groups.

An individual with a background rife with adverse childhood experiences loses the perspective that theirs is a life of privilege when compared to those who are denied even more basic human rights due to race, ethnicity, gender, orientation, or heritage. Without connection with others against which to juxtapose their experiences, they are unlikely to understand the meaning of their privilege. Understanding comes through compassionate connection with those whose lives are different and with mentors who can lead the way.

Humans are designed to be in connection with each other. We operate mostly unconsciously through hormones, synapses, and other magical pathways. Our primary operating system is our para-sympathetic nervous system – our “calm and connected” system. This part of our autonomic nervous system keeps our hearts beating, our lungs breathing, and our food digesting. The main hormone of this system is oxytocin – the hormone of love, trust, bonding, and connection. This is why isolation is so effective at crushing and changing people, and why friends and loved ones can heal and nurture new ideas.

Personal paradigms, once settled and serving us reasonably well are most likely to be changed by 2 things: Great Suffering or Great Love.

Since I work in trauma, I see how Great Suffering rips out the core of an individual and changes their very identity, their very essence. And I see how Great Love can bring healing, restoration, a new way of viewing themselves and others, and a new way of interacting in the world.

When engaging in paradigm shifting conversations, such as privilege, racism, cultural appropriation, medical routines, consumerism, religion & faith, parenting, etc., there are a few things to consider:

What is your motive for engaging in the conversation?

Are you hoping to change the other person’s perspective? In this case, you’ll have to consider if you’ll employ Great Suffering or Great Love.

Will your conversation foster human connection?

Will everyone emerge from the conversation grateful for having been a part of it?

The key to engaging in a conversation that fosters human connection, and therefore, the opportunity to encourage paradigm-shifting changes, is empathy.

Empathy is the art of considering something from the other’s vantage, i.e. wearing their shoes (metaphorically) for a mile. It is connecting by establishing emotional resonance with the other person by placing oneself in their situation and looking through their eyes. Empathy is other-centred.

Sympathy is the art of considering something from our own vantage, by drawing upon our own experiences and feelings in order to connect through a shared or common experience or history. It is connection by looking inward in order to establish a common or shared experience. Sympathy is self-centred.

Empathy is the glue that holds us together as humans sharing life on this planet together. When I’m talking about paradigm-shifting conversations, I’m talking about communication between two or more reasonable people. This does not include narcissists or sociopaths. I’m also not talking about advocacy.

Lack of empathy is a defining characteristic of narcissists and sociopaths and they are generally impervious to connection based on achieving emotional resonance or to changing their perspective based on another’s suffering. It’s probably an exercise in futility to attempt to converse in paradigm-challenging topics.

Advocacy is a form of communication that elevates the voice(s) of those who are not being heard or are unable to speak for themselves. It seeks to ensure the voices of those who are disadvantaged, marginalised, oppressed, hurt, or excluded are represented. Their voices may be angry, frustrated, grieving, incensed, or frightened. Advocacy does not target an individual for reciprocal oppression, but rather brings awareness about systems and structures that permit individuals to oppress, hurt, exclude, and marginalise others. Advocacy opens eyes and brings people to the table to talk where empathy connects individuals. Connection, built on empathy, changes individuals who then leave oppressive systems and abandon marginalising behaviours to become agents of change and advocates.

Dominant cultures and dominant paradigms do not need to advocate for their own perspective. It is unnecessary to elevate their own voices or to engage in mockery, derision, denigration, or social isolation for the few that disagree with them.

unsplash.com

If we take today’s near hysteria regarding vaccines, how many families who no longer vaccinate their children, for whatever reason, including death or injury of a previously vaccinated child, moral objection to ingredients, scientific investigation, etc., have changed their minds as a result of having their children called “crotch fruit”, or being told they are too stupid to know vaccines save lives, that the lives of their children should be left to the professionals, or that they should be arrested and have their children taken from them? I’ll go out on a limb here and say “none”. Perhaps it’s a good example of how mockery, bullying, and denigration from a dominant group is more about bonding to their own kind than actually changing someone else’s perspective.

Personal paradigms are deeply entrenched operating systems. They don’t change because someone says we are wrong or someone says we are hurting others. Where advocacy opens eyes, empathy reaches deep into our limbic system where cherished beliefs are held. Empathy disarms fear; connection heals emotional wounds.

My paradigm-shifting changes happened because I was in connection with people who cared. They validated my concerns and shared their lives with me. I am changing my perspective on many things today because of deep connections that include mutual validation, concern, and love. I would no more want to hurt someone I care about by my thoughts or actions than I want to be hurt by another’s.

As privileged and marginalised peoples, we will only learn to connect in shared human experiences as members of this planet when we connect in love and empathy.

Paradigm-shifting conversations between two or more reasonable people begin with empathy for everyone’s learned experience, whether we’re talking about racism, privilege, cultural appropriation, marginalisation, consumerism, global warming, vaccinations, obstetrical violence, birth trauma, or veganism. Life has been tough for far too many people so far. Proceed with care.

Much love,

Mother Billie

unsplash.com

Me too

Recently, #metoo went viral as hundreds of thousands of women, and some men, said “me, too, I’ve been sexually harassed, assaulted or violated”. There were stories told for the first time. There were experiences re-told through a stronger voice. And in private forums, women told of rapes, childhood molestation, being drugged, and more. Some couldn’t post “me too” on their social media stories because they didn’t want their parents to know, believed they were partly to blame, or felt it was too exposing. One woman said she didn’t want the world to know she was “weak”. When asked, she said she wasn’t strong enough to fight off her attacker and she felt ashamed for it.

There were waves of trauma as some survivors found it too overwhelming to see the hundreds of #metoo’s across their news feeds and had to disconnect until it passed. It was not comforting to know they were not alone. It was horrifying.

And this isn’t just an issue of female looking or female identifying individuals being sexually violated. Men and boys are also sexually assaulted. Yet, from a cultural perspective, the response is different. Males are not told that “boys will be boys” or "girls will be girls" and they just normally like to grope and grab and hump and fondle males. Males are rarely depicted being sexually assaulted in music videos as a form of entertainment. They are not routinely asked what they were wearing, if they were out alone, if they went to a party, or if they were drinking. As a culture, we don’t victim blame males to the same extent that we victim blame females.

“You know sexual violence knows no race or color or gender or class. But the response to sexual violence does.” ~ Tarana Burke

Tarana Burke began the “me too” campaign in 2006 as a means of helping women who had been sexually assaulted not feel so alone. It was meant especially for girls and women of colour who had survived sexual violence to inspire empowerment through empathy. It was not only “to show the world how widespread and pervasive sexual violence is, but also to let other survivors know they are not alone.”

Recently, #metoo went viral as hundreds of thousands of women, and some men, said “me, too, I’ve been sexually harassed, assaulted or violated”. There were stories told for the first time. There were experiences re-told through a stronger voice. And in private forums, women told of rapes, childhood molestation, being drugged, and more. Some couldn’t post “me too” on their social media stories because they didn’t want their parents to know, believed they were partly to blame, or felt it was too exposing. One woman said she didn’t want the world to know she was “weak”. When asked, she said she wasn’t strong enough to fight off her attacker and she felt ashamed for it.