Why I don't do vaginal exams ~ Wisdom from a Traditional Birth Companion

I let my new client know what would happen when I arrived at her home when she was in labour. We talked about sanitation measures, spending time in the kitchen, setting up the pool, and where I could take a nap if she needed some privacy. I said I would not be doing any vaginal exams as I think they’re rude, and she wept with relief.

I specialise in trauma and the majority of my clients are refugees from the medical system, running from ritual abuse and routines that protect the industry. They want someone to mentor them through to a healthy birth without the traps and trappings of the industry that removed their choice, and violated their autonomy and their dignity.

As a traditional birth attendant, I don’t do vaginal exams.

I was talking with my new client about what would likely happen when I arrived at her home when she was in labour. We talked about sanitation measures, spending time in the kitchen, setting up the pool, and where I could take a nap if she needed some privacy. I said I would not be doing any vaginal exams as I think they’re rude, and she wept with relief.

I specialise in trauma and the majority of my clients are refugees from the medical system, running from ritual abuse and routines that protect the industry. They want someone to mentor them through to a healthy birth without the traps and trappings of the industry that removed their choice, and violated their autonomy and their dignity.

We won’t go into the history of obstetrics that began with the burning of witches (midwives and healers), the rise of the man-midwife, the development of lying-in hospitals, and eventually the wholesale co-opting and medicalisation of birth. Suffice it to say that obstetrics and hospitalisation didn’t “save” women and babies (1). It created untold harm and mortality until they learned better infection control and saner behaviours. Today, it’s still leaving a trail of destruction as about 1/3 of their clients are traumatised (2,3,4) and about 1 in 8 enter parenthood with postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder (5,6,7). Suicide is a leading cause of maternal death in the first year and is highly correlated to trauma (8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16). It’s an industry out of control with unjustifiable caesarean rates, dangerous inductions for spurious reasons, and wholesale overuse of medications and interventions.

What women didn’t notice in this process of medicalisation and co-opting of their physiology for profit is that the medical industry took ownership of their vaginas once they became pregnant. Pregnancy transfers ownership of the vagina from the woman to the industry. Midwifery and obstetrical regulations stipulate that inserting an instrument, hand, or finger beyond the labia majora is a restricted practice sanctioned by legislation (17). To test this, see how long it takes for someone in the industry to file a Cease and Desist or start a campaign of persecution for the purpose of prosecution if they catch wind of anyone but one of their own sticking their fingers up there. No one but an insider sticks their fingers into their territory. It doesn’t matter who the mother gives her permission and consent to - it must be a member of the priesthood of modern medicine.

Of course, in their benevolence, they’re generally quite accommodating where partners are concerned, because most partners are male and obstetrics is exceedingly misogynistic. They value the needs and the pleasures of the D.

As a traditional birth attendant, I don’t do vaginal exams. For one thing, it’s considered a restricted practice for just the medical pundits and not doing them with my clients keeps the industry players somewhat placated knowing I’m not intruding into their turf. But the real reason is because I think they’re completely unnecessary and wouldn’t do them even if the medical folks begged me to under the guise that it would make birth safer.

To better understand the offence of the routine vaginal exam, we have to go back in time to when the male-midwife moved into the sanctity of women-centred birth and the domain of the midwife. It was profitable. And they convinced the public that they would provide a superior service based on the cultural belief of the time that women were disadvantaged by an inferior intellect and a predilection for sorcery (18,19). They also brought with them the medical perspective that women were an error of nature and that the world, and thus its inhabitants, were but a machine that could be best understood by coming to know its parts in isolation of the whole.

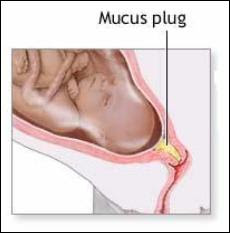

And so began dissection, mechanisation, and reducing birthing women to their parts. She became a womb expelling a foetus through a vagina. Think of today’s obstetrical “power, passenger, passage” perspective on how birth unfolds. Not much has changed in 400 years.

By sticking their fingers up there, they discovered that the cervix opens to expel the foetus. Oh, happy day! From the morgue to the birth suite, physician fingers were poking everything. Throughout the early and mid 1800’s, the infection rate in some hospitals soared as high as 60% from the mysterious childbed fever, with death rates as high as 1 in 4 (20). Nothing the doctors did was contributing to this mystery as physicians were gentlemen and gentlemen didn’t carry germs (21). And once they did accept that their filthy practices were killing women, rather than abandon the idiocy of penetrating their patients in labour, they eventually figured out how to make it less dangerous.

The practice of obstetrics has always been highly resistant to change and common sense. After all, they’ve had 400 years to figure things out and women are still birthing on their backs!

Once it was discovered that the cervix dilates as part of the labouring process, the medical industry has been fixated on that bit of tissue and made it the focus of their entire assembly line drive-through everyone-gets-what’s-on-the-menu service. That bit of tissue determines how the ward allocates services, whether the client will be permitted to stay, and how long she’ll be allowed to use their services before the next client needs the bed.

Thanks to Dr. Emanuel Friedman, who examined the cervices of 500 sedated first-time mothers in the 1950’s and plotted their dilation on a graph and matched it to the time of their birth – we now have the infamous Friedman’s Curve and the partogram.

© Evidence Based Birth

The partogram is a graph that plots cervical dilation and descent of the foetal head against a time-line. When the graph indicates that progress is slower than is allowable according to the particular chart chosen by their institution, then the practitioner is called upon to administer various interventions to speed things up to keep the labour progressing well, aka, profitably. Should these acceleration measures fail to produce a baby in a timely manner or cause foetal distress, then a caesarean section is the solution. “Failure to progress”, and the accompanying foetal distress that is often a consequence of those acceleration measures, are the leading causes of a primary caesarean (22).

Obstetrical partogram

In addition to clearing the bed for the next client, obstetrics has another reason for expediting labour. The more vaginal exams a woman receives, the greater the likelihood she’ll develop a uterine infection (23). So, once they start the poking, they need to get the baby out before their prodding adds another problem for them to solve.

In the absence of a medical situation, routine vaginal exams in labour are for the purpose of charting in order to maintain a medicalised standard of modern technocratic birth.

A labouring client will not be admitted to a hospital without a vaginal exam to determine if her dilation is far enough along for their services (unless she’s clearly pushing). And this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Early admission to the hospital results in more interventions and more caesareans than later admission (24). This is a business and time is money.

A regulated midwife attending a homebirth will likewise perform a vaginal exam upon arrival at the client’s home to determine if the client is far enough along to warrant their limited resources and time by staying and beginning the partogram or leaving and waiting to be called back later. They must also follow the rules of the hospital at which they have privileges or their regulatory agency and transport for augmentation/acceleration if the partogram shows a significant variation.

All of this is predicated on the outdated and obsolete notion that women are machines and birth is a linear process. The only thing a vaginal exam reveals is where the cervix is sitting at that particular moment and how it’s interpreted by that particular practitioner. Women are not machines and birth is not linear. Just like any mammal, birth can be slowed, stopped, or sabotaged by an unfavourable environment or reckless attendants. I’ve said for years that it’s so easy to sabotage a good birth, it’s embarrassing.

“Years ago, I was with a first-time mother planning a family-centred homebirth. She was on the clock and had a deadline. At 42 weeks gestation, she had until midnight that night to produce a baby in order to have a midwife-attended homebirth. After that, she was expected to report to the hospital for a chemical induction. As her contractions built throughout the day, her preferred midwife arrived and labour was progressing well. She was enjoying the process and the camaraderie of her sisters-in-birth. Eventually, one of the vaginal exams revealed a cervical dilation of 8 cm, indicating it was time to call in the 2nd midwife. Only, it was a midwife that had routinely upset the mother throughout pregnancy with requests for various tests and talk of all the dangers of declining routine testing. Upon learning this midwife was coming to the birth, labour slowed.

Soon enough, the 2nd midwife arrived and assumed authority over the birth process and insisted on repeated vaginal exams for the purpose of staying within the parameters of the partogram. Her vaginal exams were excruciating, no doubt because she was trying to administer a non-consenting membrane stripping as an intervention to address the slowed and almost non-existent contractions. Eventually, an exam revealed a dilation of only 6 cm. After several more hours of “torture” (according to this mother’s recount) to keep labour going rather than just leaving the mother to rest and accepting that this labour had been hijacked and needed time to regroup and restart, dilation regressed to 4 cm and the mother eventually ended up acquiescing to a hospital transfer, and experienced an all-the-bells-and-whistles birth, trauma, and postpartum PTSD.

This mother’s subsequent birth a couple of years later didn’t include inviting midwives and unfolded as it was meant to. After a day of productive and progressing labour that was clearly evident without sticking fingers up her vagina, she eventually got tired and labour slowed and stopped. She went to bed and I went home. When she woke up, labour resumed and a baby emerged swiftly and joyously. As it turns out, for her, she has a baby after a good sleep with people she trusts.”

What about the routine vaginal exams in late pregnancy? Glad you asked!

Since they don’t have good predictive value, meaning they won’t diagnose when labour will begin, how long it will take, or whether the woman’s pelvis will accommodate that particular baby prior to labour, they have 2 functions.

The first is to plan and initiate your induction.

A cervical exam provides information that is measured against a Bishop Score. A Bishop Score provides a predictive assessment on whether an induction is likely to result in a vaginal birth or is more likely to result in a caesarean for “failure to progress”. A cervix that scores higher is more likely to respond to an induction whereas a lower score indicates a less favourable outcome (25). Further, a vaginal exam allows the practitioner to begin the induction process with a membrane stripping/stretch-and-sweep.

The second purpose for routine vaginal exams in pregnancy is to build in sexual submission. It reaffirms the power dynamic where someone who is not the woman’s intimate sexual partner is allowed to penetrate her genitals at will. It makes their job much simpler once she’s is in labour. She has been trained to accept this violation.

A vaginal exam during labour might rarely be indicated when there is a problem that requires more information. A vaginal exam can help determine if there’s a possible cord prolapse requiring immediate medical attention, or can asses the position and descent of the baby to help suggest strategies to encourage the baby to move into a better position. However, when a labour is spontaneous, meaning it hasn’t been induced by any mechanical, chemical, or “natural” means, the labour isn’t augmented with artificial rupture of membranes or synthetic oxytocin, and the labouring woman is untethered and free to move as her body indicates, complications are far less likely.

Throughout my 35 years in supporting birthing families, I can say that babies do indeed come safely and spontaneously out of vaginas when there’s no one sticking their fingers up there. And they tend to come more quickly. Routine vaginal exams don’t contribute to the safety of the mother/baby. However, they do add to the safety of the practitioner who is tasked with placating the technocratic gods who demand they follow protocols and keep the wheels of the business running on track.

My reasons for not doing vaginal exams, even if the the technocratic gods gave their blessing, include:

They’re rude

They’re unnecessary

They shift the locus of power from the birthing woman to the person with the gloves

They introduce the potential for infection

They interrupt labour and can sabotage a good birth

They often hurt

They can traumatise the cervix

They can traumatise the mother

They can impact the experience of the baby

There are so many simpler ways to determine how labour is progressing

I don’t practice medicine or midwifery or engage in its absurdities

I really am not that interested in other people’s vaginas

Let’s talk about when labour does veer from a normal physiological process.

When the power dynamic places the labouring and birthing mother in charge of the experience, it actually becomes a safer and simpler process. She is the one who is experiencing the labour and birth and is the one relaying information. Only she is in direct communication with her baby. She is the one who knows when labour has exceeded her resources and she needs medical help, pharmacologic pain relief, or the reassurance of the technocratic model.

Of course, not all births unfold simply. However, my experience over these many years is that when women are not expected to submit to exams for the purpose of charting and the subsequent limitations imposed by those charts, birth unfolds a lot more simply far more often.

Much love,

Mother Billie ❤️

Endnotes

Tew, Marjorie. Safer childbirth?: a critical history of maternity care. (2013). Springer.

Garthus-Niegel, S., von Soest, T., Vollrath, M. E., & Eberhard-Gran, M. (2013). The impact of subjective birth experiences on post-traumatic stress symptoms: a longitudinal study. Archives of women's mental health, 16(1), 1-10.

Creedy, D. K., Shochet, I. M., & Horsfall, J. (2000). Childbirth and the development of acute trauma symptoms: incidence and contributing factors. Birth, 27(2), 104-111.

Schwab, W., Marth, C., & Bergant, A. M. (2012). Post-traumatic stress disorder post partum. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde, 72(01), 56-63.

Montmasson, H., Bertrand, P., Perrotin, F., & El-Hage, W. (2012). Predictors of postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder in primiparous mothers. Journal de gynecologie, obstetrique et biologie de la reproduction, 41(6), 553-560.

Beck, C. T., Gable, R. K., Sakala, C., & Declercq, E. R. (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder in new mothers: Results from a two‐stage US National Survey. Birth, 38(3), 216-227.

Shaban, Z., Dolatian, M., Shams, J., Alavi-Majd, H., Mahmoodi, Z., & Sajjadi, H. (2013). Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following childbirth: prevalence and contributing factors. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 15(3), 177-182.

Oates, M. (2003). Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. British medical bulletin, 67(1), 219-229.

Oates, M. (2003). Suicide: the leading cause of maternal death. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 183(4), 279-281.

Cantwell, R., Clutton-Brock, T., Cooper, G., Dawson, A., Drife, J., Garrod, D., Harper, A., Hulbert, D., Lucas, S., McClure, J. and Millward-Sadler, H. (2011). Saving Mothers' Lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006-2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology, 118, 1-203.

Austin, M. P., Kildea, S., & Sullivan, E. (2007). Maternal mortality and psychiatric morbidity in the perinatal period: challenges and opportunities for prevention in the Australian setting. Medical Journal of Australia, 186(7), 364-367

Palladino, C. L., Singh, V., Campbell, J., Flynn, H., & Gold, K. (2011). Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Obstetrics and gynecology, 118(5), 1056.

Grigoriadis, S., Wilton, A.S., Kurdyak, P.A., Rhodes, A.E., VonderPorten, E.H., Levitt, A., Cheung, A. and Vigod, S.N. (2017). Perinatal suicide in Ontario, Canada: a 15-year population-based study. Cmaj, 189(34), E1085-E1092.

CEMD (Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths) (2001) Why Mothers Die 1997–1999. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

Sareen, J., Cox, B. J., Stein, M. B., Afifi, T. O., Fleet, C., & Asmundson, G. J. (2007). Physical and mental comorbidity, disability, and suicidal behavior associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in a large community sample. Psychosomatic medicine, 69(3), 242-248.

Hudenko, William, Homaifar, Beeta, and Wortzel, Hal. (July 2016). The Relationship Between PTSD and Suicide. PTSD: National Center for PTSD, U.S. Department of Veterans Affair.

Act, Ontario Midwifery. "SO 1991, c. 31." (1991).

Smith Adams, K. L. (1988). From 'the help of grave and modest women' to 'the care of men of sense': the transition from female midwifery to male obstetrics in early modern England. (Master’s thesis, Portland State University.

Burrows, E. G., & Wallace, M. (1998). Gotham: a history of New York City to 1898. Oxford University Press.

Semmelweis, I. (1983). Etiology, concept, and prophylaxis of childbed fever. Carter KC, ed. Madison, WI.

Halberg, F., Smith, H. N., Cornélissen, G., Delmore, P., Schwartzkopff, O., & International BIOCOS Group. (2000). Hurdles to asepsis, universal literacy and chronobiology-all to be overcome. Neuroendocrinology Letters, 21(2), 145-160.

Caughey, A. B., Cahill, A. G., Guise, J. M., Rouse, D. J., & American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2014). Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 210(3), 179-193.

Curtin, W. M., Katzman, P. J., Florescue, H., Metlay, L. A., & Ural, S. H. (2015). Intrapartum fever, epidural analgesia and histologic chorioamnionitis. Journal of Perinatology, 35(6), 396-400.

Kauffman, E., Souter, V. L., Katon, J. G., & Sitcov, K. (2016). Cervical dilation on admission in term spontaneous labor and maternal and newborn outcomes. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 127(3), 481-488.

Vrouenraets, F. P., Roumen, F. J., Dehing, C. J., Van den Akker, E. S., Aarts, M. J., & Scheve, E. J. (2005). Bishop score and risk of cesarean delivery after induction of labor in nulliparous women. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 105(4), 690-697.

Beyond the Shot: Preventing Postpartum Haemorrhage ~ Wisdom from a Traditional Birth Companion

Postpartum haemorrhage is a complication that can happen in any birth setting, although it’s more likely in a hospital. Despite the universal application of “active management” as a prevention, the rate of haemorrhage due to uterine atony has been steadily climbing in developed nations.

“Active management of the 3rd stage”, is an intervention for the birth of the placenta, the time when women are most likely to lose a significant amount of blood. It involves injecting the mother with a uterotonic (something to make the uterus contract), usually synthetic oxytocin, as soon as the baby is born, and it may include some other steps like early cord clamping or pulling on the umbilical cord depending on the protocol used. This intervention is applied to all birthing women in all hospitals, birth centres, and homes with few exceptions.

You’d think if every mother everywhere gets this injection, then it must be a good thing. Well, that’s the thing about obstetrics. It tends to take an intervention that might be suitable for some clients in certain situations and applies it to everyone. And the results are increasingly worrisome.

© Billie Harrigan Consulting

“We don’t birth according to the science. We birth according to what we believe.

And we don’t believe the science.”

~ Mother Billie

Hospital-based birth presents some unique safety challenges. Over the years, there have been various efforts to reduce the increased risks. Some of them have been successful, such as hand washing and sanitation to reduce infections, and some of them not at all successful, such as any attempt to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections.

Postpartum haemorrhage is a complication that can happen in any birth setting, although it’s more likely in a hospital (1,2,3,4). Despite the universal application of “active management” as a prevention, the rate of haemorrhage due to uterine atony has been steadily climbing in developed nations (5,6,7,8).

“Active management of the 3rd stage”, is an intervention for the birth of the placenta, the time when women are most likely to lose a significant amount of blood. It involves injecting the mother with a uterotonic (something to make the uterus contract), usually synthetic oxytocin, as soon as the baby is born, and it may include some other steps like early cord clamping or pulling on the umbilical cord depending on the protocol used. This intervention is applied to all birthing women in all hospitals, birth centres, and homes with few exceptions.

You’d think if every mother everywhere gets this injection, then it must be a good thing. Well, that’s the thing about obstetrics. It tends to take an intervention that might be suitable for some clients in certain situations and applies it to everyone. And the results are increasingly worrisome.

To begin – what is a postpartum haemorrhage?

The general definition of postpartum haemorrhage is blood loss of 500mls in the first 24 hours following a vaginal birth, or blood loss of 1000mls following caesarean surgery. A severe postpartum haemorrhage is loss of 1000mls after a vaginal birth (or 1500mls in some locations).

The first question we need to ask is why 500mls was chosen as the threshold for defining a haemorrhage? When no uterotonics are used and postpartum blood loss is measured, the average blood loss in the first hours is actually around 500mls (9,10). Estimating blood loss by looking at it is fairly inaccurate and most observers tend to underestimate blood loss (11,12,13). This means that healthy births that look like they didn’t release much blood have actually released about 500mls in the first hours, which is technically a haemorrhage.

Since 500mls has been selected as the threshold for haemorrhage, the effectiveness of every intervention is based on its ability to reduce the average amount of blood a woman releases in the first hours after birth, because now average is considered pathological.

If we move away from pathologising average amounts of blood, then a new definition of postpartum haemorrhage might be considered. A haemorrhage could be considered as any blood loss that exceeds that mother’s physiological capacity to accommodate it without any accompanying morbidity.

For a mother with adequate iron stores and a healthy blood volume expansion, which is about 1450mls of additional circulating blood, a loss of over 500mls may present no additional challenges. In fact, most women who experience a blood loss of over 500mls receive no clinical intervention or experience any serious consequences (14,15,16). And yet, for a mother who has had a challenging pregnancy or other health concerns, with poor blood volume expansion and exhausted iron stores, a loss of much less might present difficulties and require treatment.

It’s hard to get estimates on the prevalence of postpartum haemorrhages as there are profound differences in reported outcomes from different countries, facilities, and clientele (17). This tells us there are significant differences in how blood loss is measured, the health of the clientele, and what is done to the birthing client that either improves or exacerbates bleeding. And because women are not standardised machines, there is tremendous variability between individuals.

Why does it happen?

About 80% of the time, a postpartum haemorrhage is the result of uterine atony, which is a lack of effective contractions (5,18). Without effective contractions, the blood vessels behind the placenta fail to close and blood continues to flow freely. It can also be caused by physical trauma, for example lacerations in the vagina or cervix from tearing, forceps, or an episiotomy. Uterine rupture can cause a haemorrhage, as can a placental abruption, where the placenta prematurely separates from the uterine wall. Retained placental tissue or blood clotting disorders in the mother can also cause a haemorrhage.

Active management to the rescue!

Active management only addresses uterine atony. It can’t help when the reason for the haemorrhage is physical trauma from tearing or cutting, or address a blood clotting disorder. The World Health Organisation and most medical and midwifery associations recommend giving 100% of women an injection of synthetic oxytocin just after the baby arrives as a means of preventing postpartum haemorrhage (19). Oxytocin is a naturally occurring hormone that causes the uterus to contract. It’s the primary hormone of labour. An injection of 10IU of synthetic oxytocin, either intramuscular or added to an IV, is the recommended intervention. In low resource settings where there is no synthetic oxytocin, which requires stable temperature and a skilled attendant to administer it, then an oral dose of misoprostol is recommended as a preventive.

REX/Shutterstock

What about that shot of synthetic oxytocin?

Synthetic oxytocin is a drug that is marketed under the brand names Pitocin, Syntocinon, and a number of lesser-known brands. It’s a clear aqueous solution that contains a chemically identical synthetic version of naturally-occurring oxytocin. Naturally-occurring oxytocin is produced in the brain by the hypothalamus and released both as a neurotransmitter across the brain facilitating feelings of love, bonding, trust, empathy, and compassion, and as a hormone through the posterior pituitary gland into the blood where it acts on smooth muscles in pulses or waves. Synthetic oxytocin is delivered through a syringe into the mother’s muscle (usually the thigh or bum) or through an IV directly into the blood stream. It does not cross the mother’s blood-brain barrier and doesn’t support bonding with the baby.

Looking at Pitocin, we see that it also contains 0.5% Chlorobutanol, a chloroform derivative as a preservative, acetic acid to adjust its pH, and may contain up to 16% of total impurities (20).

When given as an injection, the uterus responds by contracting within 3-5 minutes and lasts for 2-3 hours. When given in an IV, the uterus responds almost immediately and it lasts about an hour. It’s removed from maternal plasma through the liver and kidneys.

Just like any drug, synthetic oxytocin comes with risks, including

Anaphylactic reaction – an allergic reaction where the individual may stop breathing

Uterine hypertonicity, spasm, or tetanic contraction

Uterine rupture

Premature ventricular contractions – feels like heart palpitations or the heart is “skipping a beat”

Pelvic haematoma – a blood clot similar to a deep bruise

Hypertensive episodes – spiking blood pressure

Cardiac arrhythmia – fluctuations in heartbeat

Nausea and vomiting

Headache, loss of memory, confusion

Loss of coordination, fainting

Seizures

Subarachnoid haemorrhage – bleeding beneath the membrane that covers the brain. This can lead to stroke, seizures, brain damage, and death

Fatal afibrinogenemia – an absence of fibrinogen circulating in the blood which is needed for blood clotting. This leads to sudden and uncontrollable haemorrhage until death

Postpartum haemorrhage

Prolonged bleeding in the days and weeks after birth

“The possibility of increased blood loss and afibrinogenemia should be kept in mind when administering the drug.” ~ drugs.com

The preservative Chlorobutanol has a half-life of 10 days and is anti-diuretic, meaning it will interfere with normal elimination for up to 10 days and may contribute to increased breast engorgement. An allergic reaction can cause dermatitis, usually beginning on the face and chest. It is known to cause light headedness, ataxia (loss of coordination, speech, or eye movement), and nightmares.

Does this intervention work?

The most recent Cochrane Review (2019) (17), reveals that this recommendation is based on studies with “very low” to “moderate” level quality. According to the review, using synthetic oxytocin after the birth of the baby

May reduce the risk of blood loss of 500 mL after delivery (low-quality evidence)

May reduce the risk of blood loss of 1000 mL after delivery (low-quality evidence)

Probably reduces the need for additional uterotonics (moderate-level evidence)

May be no difference in the risk of needing a blood transfusion compared to no intervention (low-quality evidence)

May be associated with an increased risk of a third stage greater than 30 minutes (moderate-quality evidence)

An earlier Cochrane Review revealed that it reduces average blood loss by about 80mls (21). This is usually enough to bring the average blood loss below 500mls thereby avoiding a diagnosis of postpartum haemorrhage. When it comes to severe postpartum haemorrhage of over 1000mls blood loss, it only shows a marginal improvement over expectant management (watching and waiting) (17), and it doesn’t lessen the need for blood transfusion (22).

What else does this drug do?

Synthetic oxytocin dramatically increases the incidence of postpartum depression and anxiety in the first year. In women with a history of depression or anxiety, exposure to this drug increases the risk by a whopping 36%, and for women with no history of depression or anxiety, this drug increases the risk by 32% (23).

Synthetic oxytocin is also associated with greater breastfeeding failure and somatisation symptoms (pain with no known organic cause) (24).

Asking the big questions

Is reducing the average amount of blood loss by about 80mls based on an arbitrary threshold of 500mls worth the risks of this intervention? Are there safer ways to reduce the potential for haemorrhage?

Identifying the risks

There are certain factors that increase the potential for haemorrhage. The rising rates of postpartum haemorrhage have been linked to rising rates of induction and augmentation (25). More women with previous caesareans also mean more haemorrhages, possibly because there are more problems with how the placenta inserts itself in the uterus. Twins or polyhydramnios (excessive water) that overly distends the uterus, is a risk factor. As is pre-eclampsia, chorioamnionitis, and obesity (26).

As mentioned before, hospital birth is a significant risk for a haemorrhage of 1000mls or more (1,2,3,4). This isn’t surprising since hospital births include inductions, augmentations, and complicated pregnancies. However, when comparing the same low risk groups, hospital birth is still an independent risk factor. It’s also the place that is most likely to disrupt the physiology of birth with ritual and routine.

And this is where it gets even more interesting. Studies have shown that when comparing active management with physiological management, that jab of synthetic oxytocin can reduce average blood loss by about 80mls. The problem with these studies is that hospital births are not generally places where physiology is understood or supported. Meaning they might be comparing the same management except that one includes a shot and one doesn’t.

For example, early clamping of the umbilical cord became a world-wide intervention based on terrible presumption and continued in light of great research due to entrenched habit and ego. In one study, women who had a “physiological” 3rd stage had greater postpartum haemorrhages over 1000mls compared to actively managed women (27). The authors noted that the more the placenta weighed, the greater the blood loss. And, why did these placentas weigh so much? Because early clamping of the cord was the usual practice. Draining the cord to reduce the blood volume of the placenta reduces haemorrhage (28) and of course that blood belongs in the baby, not a pail on the floor.

Early cord clamping - Getty Images

In a study where midwives were familiar with the normal birth of the placenta and were less likely to disrupt it, active management doubled haemorrhages over 1000mls (29). In another study where the birth of the placenta was supported with “holistic” care, active management increased the risk of haemorrhage by 7-8-fold (30).

Feeding the mother and the uterus

Labour is an intense activity and requires about 1000 calories of energy per hour. Denying mothers food during labour was an attempt in the 1940’s to prevent her from vomiting under general anesthesia and then breathing in the vomit (31). We know that obstetrics is slow to change, after all, they’ve had 400 years to get women off their backs! Most women are still denied food in a hospital. No one is using the anesthesia of the 1940’s. Forced fasting doesn’t prevent vomiting (32), it only makes the mother more miserable and contributes to a longer labour (33). And longer labours are more likely to be augmented, putting the mother at risk for haemorrhage.

Perhaps a hungry uterus is one that doesn’t contract after the birth of the baby. A study that compared the usual shot of synthetic oxytocin in the mum’s bum to giving her some lovely dates to eat after the birth showed that eating dates was more effective in reducing blood loss than the injection (34). I remember discussing this with some traditional midwives who reported the same great results from giving the mother apricot nectar after the birth. Nourishing mothers is just good care.

© Billie Harrigan Consulting

What is this holistic care that makes birth so much safer?

Holistic care acknowledges that we are mammals and need the same conditions as any mammal giving birth. Birth is a time of reconnection where mother and baby’s interdependence moves from womb to arms. Both the mother and the baby have been waiting for this moment to gaze into each other’s eyes and to say “I know you”. Supporting this reconnection is key to ensuring the birth of the placenta unfolds safely.

And we return to oxytocin, the kind our brain produces, to ensure this reconnection is joyous and safe. Oxytocin is the hormone of love, bonding, trust, empathy, and the one that contracts the uterus and ejects the milk. Oxytocin is also the hormone of orgasms. Anything that disrupts a good orgasm is what disrupts the bonding and the expulsion of the placenta.

Oxytocin is easily encouraged, but it’s also easily disrupted.

holistic care

The room is warm, dimly lit, a sanctuary encircling the mother with love and support. She is nourished and feels safe and cared for. Her labour has begun spontaneously, no drugs, no stretch-and-sweep, and no “natural” induction. The hormones of birth are primed and mother and baby are prepared for this transition from womb to arms. Their hearts cry out for each other; their very skin crawling in anticipation of each other’s touch. The mother heeds the calls of her labour and sways, groans, rises, and pushes. The baby emerges with its protective coating of vernix and is colonised by its mother’s flora. The mother’s waiting hands draw her baby up to her chest which has already adjusted its temperature to ensure the baby is kept warm through her own bodily heat and skin-to-skin contact. The baby smells divine! Its head is releasing pheromones drawn in with each of the mother’s breaths. This baby’s scent reaches the olfactory bulb in the limbic system where the amygdala creates a permanent memory of this precious child. The hypothalamus receives the message that the newest member of our humanity is earthside and sends a gush of oxytocin to ensure bonding, preparation for breastfeeding, and a message to the uterus to contract to begin expelling the placenta. As mother and baby continue to explore each other, the placenta is released and mother feels the urge to expel it. She moves freely, adjusting, and rising to use gravity to her advantage again as it falls gently into a bowl. The bowl is placed next to her as there’s no rush to sever the connection between the baby and its placenta until baby is secure in its connection to its mother. Then she rests, with her baby nestled between her breasts, beginning its journey to her nipple to receive the long-awaited nectar. Both are wrapped in a blanket to ensure they are warm and cocooned. A cup of warm sweet tea and a snack is brought to her and she admires her courage, her strength, and her baby at her breast. Her uterus contracts as it is nourished and charged by the suckling of the baby. Her bleeding is much like a heavy period for a few days, then lessens, and is generally finished within 2-3 weeks.

BSIP/Getty Images

usual care

The room is cool and bright, smelling of antiseptic, the shoes of exhausted nurses and midwives, and echoing the cries of others down the hall. The mother is lying on a narrow bed thrashing as the waves hit, unable to get up, run, leave. The belts are wrapped around her belly measuring each wave requiring her to limit her movement to meet their unfeeling demands. She is exposed and hungry with an IV feeding her fluids and keeping an open port in anticipation of an emergency. On her back, her waves are met with instructions to pull back her legs, bow her head, and hold her breath and push to the count of ten as the room fills with strangers, lights point at her vulva, and the appointed one sits between her legs. The resuscitation station has been warmed and primed to receive her newly born baby. The appointed one may choose to cut open her perineum. As the baby emerges, it is received by the appointed one who may also choose to separate the baby from its source of blood and oxygen through careless ritual. The mother is injected with a dangerous drug and the baby is dried. A hat is placed on the baby’s head so the glory of its scent cannot reach the mother’s limbic system to register this new life. The baby may be wrapped up, preventing the benefits of skin-to-skin, including colonising the mother’s flora, regulating its temperature, and preventing postpartum haemorrhage (35). The baby may be placed on its mother’s chest or it may go to the warming station for weighing and injecting. Once on its mother’s chest, strange hands continue to probe, measure, and instruct. In time, there is food. Her bleeding remains heavy for the first 2 weeks and tends to finish by her 6-week postpartum check-up.

Image by Engin Akyurt from Pixabay

But, but … the hat!

Since the placing of hat is a ritual that is often replicated at home, thereby increasing the potential for haemorrhage, let’s talk some more about it.

Newborn babies don’t regulate their body temperature with the same efficiency as adults. They need help in staying warm. However, biology is glorious and rarely needs our routines. The space between the mother’s breasts adjusts its temperature to ensure the baby is kept at the right temperature, even accommodating the different needs of twins (36). This requires skin-to-skin contact. The other regulating factor is the temperature of the room. A warm room keeps the baby warm (37).

It’s believed that because babies have large heads, they are more likely to lose heat through their heads, so putting a hat on it will keep the baby warm. Only it doesn’t. Stockinette hats don’t affect the core temperature of the baby (38,39). Thermal hats do, and they’re an important part of caring for and transporting a vulnerable premature baby. The only thing knitted hats do is prevent the mother from breathing in the baby’s scent and releasing more oxytocin in response. It’s a foolish ritual.

The elements of holistic care:

Wait for spontaneous labour where possible

Freedom of movement throughout labour to avoid a long labour and augmentation

Nourish the mother with food and drink according to her preference

Warmth and privacy

Spontaneous pushing in the mother’s preferred position

No clamping or cutting of the cord until the placenta is birthed

Immediate skin-to-skin

No hat on the baby

Quiet, private, and supported time between mother and baby

Placenta is birthed by maternal effort aided by gravity

Nourishment for the mother soon after the birth

Ongoing comfort, warmth, and autonomy for the mother

Conclusion

Active management appears to be a dubious and somewhat dangerous intervention that was introduced to overcome obstetrics’ lack of understanding of physiology and their pathological need to disrupt it.

When birth is supported with holistic care, it’s up to 7-8 times safer than routine hospital care with the routine jab. Preventing postpartum haemorrhage comes down to understanding and respecting the physiology of birth, the intense need that mothers and babies have for one another, and not getting in the way. And if there’s a problem, then it requires prompt treatment, but not before to cause the problem.

Much love,

Mother Billie

Endnotes

Scarf, V.L., Rossiter, C., Vedam, S., Dahlen, H.G., Ellwood, D., Forster, D., Foureur, M.J., McLachlan, H., Oats, J., Sibbritt, D. & Thornton, C. (2018). Maternal and perinatal outcomes by planned place of birth among women with low-risk pregnancies in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Midwifery, 62, 240-255.

Hutton, E. K., Cappelletti, A., Reitsma, A. H., Simioni, J., Horne, J., McGregor, C., & Ahmed, R. J. (2016). Outcomes associated with planned place of birth among women with low-risk pregnancies. Cmaj, 188(5), E80-E90.

Blixa, E., Huitfeldtb, A. S., Øiand, P., Straumea, B., & Kumle, M. (2014). Outcomes of planned home births and planned hospital births in low-risk women in Norway between 1990 and 2007: A retrospective cohort study. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare. Volume 3, Issue 4, December 2012, Pages 147–153.

Nove, A., Berrington, A., & Matthews, Z. (2012). Comparing the odds of postpartum haemorrhage in planned home birth against planned hospital birth: results of an observational study of over 500,000 maternities in the UK. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 12(1), 130.

Lutomski, J., Byrne, B., Devane, D., & Greene, R. (2012). Increasing trends in atonic postpartum haemorrhage in Ireland: An 11-year population-based cohort study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 119(3), 306-314.

Callaghan, W. M., Kuklina, E. V., & Berg, C. J. (2010). Trends in postpartum hemorrhage: United States, 1994–2006. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 202(4), 353-e1.

Knight, M., Callaghan, W.M., Berg, C., Alexander, S., Bouvier-Colle, M.H., Ford, J.B., Joseph, K.S., Lewis, G., Liston, R.M., Roberts, C.L. & Oats, J. (2009). Trends in postpartum hemorrhage in high resource countries: a review and recommendations from the International Postpartum Hemorrhage Collaborative Group. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 9(1), 55.

Roberts, C. L., Ford, J. B., Algert, C. S., Bell, J. C., Simpson, J. M., & Morris, J. M. (2009). Trends in adverse maternal outcomes during childbirth: a population-based study of severe maternal morbidity. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 9(1), 7.

Nordström, L., Fogelstam, K., Fridman, G., Larsson, A., & Rydhstroem, H. (1997). Routine oxytocin in the third stage of labour: a placebo controlled randomised trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 104(7), 781-786.

Prichard, J. A., Baldwin, R. M., Dickey, J. C., & Wiggins, K. M. (1962). Blood volume changes in pregnancy and the puerperium. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 84, 1271-1282.

Prichard, J. A., Baldwin, R. M., Dickey, J. C., & Wiggins, K. M. (1962). Blood volume changes in pregnancy and the puerperium. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 84, 1271-1282.

Bloomfield, T. H., & Gordon, H. (1990). Reaction to blood loss at delivery. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 10(sup2), S13-S16.

Prasertcharoensuk, W., Swadpanich, U., & Lumbiganon, P. (2000). Accuracy of the blood loss estimation in the third stage of labor. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 71(1), 69-70.

Carroli, G., Cuesta, C., Abalos, E., & Gulmezoglu, A. M. (2008). Epidemiology of postpartum haemorrhage: a systematic review. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology, 22(6), 999-1012.

Selo-Ojeme, D. O. (2002). Primary postpartum haemorrhage. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 22(5), 463-469.

Prendiville, W. J., Harding, J. E., Elbourne, D. R., & Stirrat, G. M. (1988). The Bristol third stage trial: active versus physiological management of third stage of labour. Bmj, 297(6659), 1295-1300.

Salati, J. A., Leathersich, S. J., Williams, M. J., Cuthbert, A., & Tolosa, J. E. (2019). Prophylactic oxytocin for the third stage of labour to prevent postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (4).

Bateman, B. T., Berman, M. F., Riley, L. E., & Leffert, L. R. (2010). The epidemiology of postpartum hemorrhage in a large, nationwide sample of deliveries. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 110(5), 1368-1373.

World Health Organization. (2012). WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. World Health Organization.

Drugs.com. Retrieved from https://www.drugs.com/pro/pitocin.html April 10, 2020.

Prendiville, W. J., Elbourne, D., & McDonald, S. J. (2000). Active versus expectant management in the third stage of labour. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (3).

Sloan, N. L., Durocher, J., Aldrich, T., Blum, J., & Winikoff, B. (2010). What measured blood loss tells us about postpartum bleeding: a systematic review. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 117(7), 788-800.

Kroll‐Desrosiers, A. R., Nephew, B. C., Babb, J. A., Guilarte‐Walker, Y., Moore Simas, T. A., & Deligiannidis, K. M. (2017). Association of peripartum synthetic oxytocin administration and depressive and anxiety disorders within the first postpartum year. Depression and anxiety, 34(2), 137-146.

Gu, V., Feeley, N., Gold, I., Hayton, B., Robins, S., Mackinnon, A., Samuel, S., Carter, C.S. & Zelkowitz, P. (2016). Intrapartum synthetic oxytocin and its effects on maternal well‐being at 2 months postpartum. Birth, 43(1), 28-35.

Kramer, M. S., Dahhou, M., Vallerand, D., Liston, R., & Joseph, K. S. (2011). Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage: can we explain the recent temporal increase?. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 33(8), 810-819.

Wetta, L. A., Szychowski, J. M., Seals, S., Mancuso, M. S., Biggio, J. R., & Tita, A. T. (2013). Risk factors for uterine atony/postpartum hemorrhage requiring treatment after vaginal delivery. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 209(1), 51-e1.

Jangsten, E., Mattsson, L. Å., Lyckestam, I., Hellström, A. L., & Berg, M. (2011). A comparison of active management and expectant management of the third stage of labour: a Swedish randomised controlled trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 118(3), 362-369.

Mohamed, A., Bayoumy, H. A., Abou-Gamrah, A. A. S., & El-Shahawy, A. A. S. (2017). Placental cord drainage versus no placental drainage in the management of third stage of labour: Randomized controlled trial. The Egyptian Journal of Hospital Medicine, 68(1), 1042-1048.

Davis, D., Baddock, S., Pairman, S., Hunter, M., Benn, C., Anderson, J., Dixon, L. & Herbison, P. (2016). Risk of severe postpartum hemorrhage in low-risk childbearing women in new zealand: exploring the effect of place of birth and comparing third stage management of labor-Birth (Berkeley, Calif.)-Vol. 39, 2-ISBN: 1523-536X-p. 98-105.

Fahy, K., Hastie, C., Bisits, A., Marsh, C., Smith, L., & Saxton, A. (2010). Holistic physiological care compared with active management of the third stage of labour for women at low risk of postpartum haemorrhage: a cohort study. Women and Birth, 23(4), 146-152.

Mendelson, C. L. (1946). The aspiration of stomach contents into the lungs during obstetric anesthesia. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 1(6), 837-839.

Ludka, L. M., & Roberts, C. C. (1993). Eating and drinking in labor: a literature review. Journal of Nurse-Midwifery, 38(4), 199-207.

Rahmani, R., Khakbazan, Z., Yavari, P., Granmayeh, M., & Yavari, L. (2012). Effect of oral carbohydrate intake on labor progress: randomized controlled trial. Iranian journal of public health, 41(11), 59.

Khadem, N., Sharaphy, A., Latifnejad, R., Hammod, N., & Ibrahimzadeh, S. (2007). Comparing the efficacy of dates and oxytocin in the management of postpartum hemorrhage. Shiraz E-Medical Journal, 8(2), 64-71.

Saxton, A., Fahy, K., Rolfe, M., Skinner, V., & Hastie, C. (2015). Does skin-to-skin contact and breast feeding at birth affect the rate of primary postpartum haemorrhage: Results of a cohort study. Midwifery, 31(11), 1110-1117.

Ludington‐Hoe, S. M., Lewis, T., Morgan, K., Cong, X., Anderson, L., & Reese, S. (2006). Breast and infant temperatures with twins during shared kangaroo care. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 35(2), 223-231.

Perlman, J., & Kjaer, K. (2016). Neonatal and maternal temperature regulation during and after delivery. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 123(1), 168-172.

De Saintonge, D. C., Cross, K. W., Shathorn, M. K., Lewis, S. R., & Stothers, J. K. (1979). Hats for the newborn infant. Br Med J, 2(6190), 570-571.

Coles, E. C., & Valman, H. B. (1979). Hats for the newborn infant. British medical journal, 2(6192), 734.

The Art of Palpation ~ Wisdom from a Traditional Birth Companion

Palpation is the act of using one’s hands to figure out something on or in a body. In maternity services, the practitioner routinely palpates the pregnant belly to assess the position and size of the foetus.

After the male midwife, which later became the obstetrician, infiltrated birth services and paternalized it into a male-centric, provider-centric practice, they’ve been “discovering” all kinds of things that were just normally known and carried out by midwives for centuries. Among them is the standard way to palpate a pregnant belly.

I tend to see palpation through a different lens. I feel it’s more about building a relationship with the baby than anything else.

Nana playing with/palpating her granddaughter before she was born. ©Billie Harrigan Consulting

Palpation is the act of using one’s hands to figure out something on or in a body. In maternity services, the practitioner routinely palpates the pregnant belly to assess the position and size of the foetus.

After the male midwife, which later became the obstetrician, infiltrated birth services and paternalized it into a male-centric, provider-centric practice, they’ve been “discovering” all kinds of things that were just normally known and carried out by midwives for centuries. Among them is the standard way to palpate a pregnant belly.

German obstetrician-gynaecologist Christian Gerhard Leopold (1846-1911) is credited with the obstetrical manoeuvre used today to palpate pregnant bellies called ‘Leopold’s Manoeuvre’.

Leopold’s Manoeuvre is a series of 4 specific actions. These 4 actions, along with an assessment of the maternal pelvic shape will help the practitioner to determine if complications will occur during delivery and whether a caesarean should be recommended. They think of it much like a crystal ball that somehow predicts the future. In the provider-centric world of maternity services, it’s another way the practitioner replaces the pregnant mother as the expert on her body and her birth and minimises the power of the birth dance where the mother and baby work together through movement to bring the baby earthside.

Manoeuvre one: Fundal Grip

The practitioner walks their hands up the sides of the uterus to the top of the uterus, called the ‘fundus’. Palpating the upper abdomen will determine if the foetus is lying longitudinal (up/down), oblique (on an angle), or transverse (side-to-side). If the baby is longitudinal, palpating the upper abdomen should determine if it’s a bum or a head.

Manoeuvre two: Umbilical Grip

Next is to determine where the foetal back is lying. By placing hands on either side of the mid-abdomen, the practitioner applies deep pressure on alternating sides to determine where the back is and where the extremities are (arms and legs).

Leopold’s Manoeuvres - public domain

Manoeuvre three: Pawlick’s Grip

This is also named after a male obstetrician-gynaecologist, Karel Pawlick (1849-1914). This step determines how much of the foetus is above the pelvic inlet. The practitioner uses their fingers and thumb to grasp the lower abdomen, just above the pubic bone (pubic symphysis) to feel how much of the foetus can be felt above the pubic bone.

Manoeuvre four: Pelvic Grip

The practitioner faces the patient’s feet and tries to locate the foetus’ brow by placing both hands on the lower abdomen and moving the fingers of both hands towards the pubis by sliding the hands over the sides of the patient’s uterus. On the side where there is the greatest resistance to the practitioner’s descending fingers is the baby’s brow. A well-flexed head, meaning the chin is tucked down towards the chest, will be on the opposite side of the foetal back. If the head is extended, that is, looking straight ahead or upwards, the back of the head is felt on the same side where the back was found. If the brow cannot be found, the head is descended into the pelvis.

With the routine overuse of ultrasound, many practitioners are losing the art of palpation. Routine multiple ultrasounds are now taking the place of non-invasive and non-risky palpation to assess foetal size (with varying degrees of accuracy), amniotic fluid volume (with varying degrees of accuracy), and position of the baby (with a great deal of accuracy). It could be that since ultrasound is very accurate at determining position, practitioners are losing confidence in their own skills.

As a Traditional Birth Attendant, I like palpating pregnant bellies. I especially like it as a grandmother (Nana). Nothing delights me more than playing with my own grandchildren inside their mother’s bellies. In fact, Nana has turned her own grandchild from breech to cephalic. It’s a simple skill that tends to make me a more useful grandmother.

In all the texts I scoured that discusses how to do Leopold’s Manoeuvre, not once was the foetus ever considered as a sentient member of the procedure. The mother’s comfort is often considered, but primarily, it’s about the practitioner doing something to the client to gather information.

I tend to see palpation through a different lens. I feel it’s more about building a relationship with the baby than anything else. After all, if I’m going to be invited to the birth, the baby should know who I am and whether I am someone they can trust to care for their mummy and therefore take care of them.

In my relationship with pregnant families, the first part of palpating a pregnant belly is to ask the mother if she would like this. She doesn’t have to submit to this. This is her choice. I’ve had clients with a history of sexual assault where this was a very threatening idea that someone would be touching their belly and never wanted it. Instead, they just told us where the baby was and what their guess was on how big the baby was. As it turns out, maternal guessing is pretty accurate and often beats the guesses of ultrasounds or experienced practitioners (1). Another client liked palpation, but could only do it sitting up with one hand over her breasts and one protecting her groin.

If the mother agrees to palpation, then I always suggest she go relieve her bladder first. There’s nothing worse than someone playing with your belly and a full bladder. It’s a recipe for leaking out a wee drip or a pent-up fart.

I have a nice couch by a sunny window that clients are invited to lie down on with as many pillows behind them as feels comfortable. I tend to sit on the couch with them nestled beside their legs.

Now here comes the most important part of palpation:

I introduce myself to the baby.

I say hello to the baby. I tell them my name and that I’m a friend of their mummy and daddy. I let them know that Nana often has cold hands.

I start very gently and talk to the baby the whole time. There are no pre-determined set of manoeuvres as this is usually led by the baby. I may find their little bum and squeal with delight! I talk about how much they’re growing. I invite them to play with me. Sometimes their little foot will poke out to start a little game with me. I’ll ask them to show me what position they’re in and if they’d be ok with us listening to their heartbeat with a fetoscope. If my hands are going to go lower on the mother’s abdomen to where a head might be nestled, I always ask permission from the mother before touching her anywhere close to her pubic bone. Likewise, if the parents want a measurement of fundal height, it’s the mother that places the end of the measuring tape on the top of her pubic bone. There’s no need for someone else to be rooting around down there. Once mum picks her spot where the tape measure starts, then that also helps to eliminate measuring errors that can come with multiple people measuring her belly and placing the tape differently.

Some babies become quite playful. And some will lie quietly, listening to me, deciding if I am friend or foe. It becomes quite easy to sense the baby’s receptivity. A baby who has taken a journey along with their mother through previous obstetric mistreatment or disrespectful prenatal visits will often lie quietly, perhaps taking in their mother’s reactions. It may take another visit to warm up to me and become more playful. I tell them that by the time they arrive, I hope we’ll be good friends.

Through gentle palpation, the baby and I are getting to know each other. The parents and I are building trust. We’re having fun! And through gentle touch, we discover where the baby is positioned at that particular moment. It’s not predictive of much else. Even persistently breech babies have turned in labour when I’ve been present. Perhaps in the presence of calm and loving family and birth attendant, the babies felt it a simple matter to rotate and come out head first.

Through gentle palpation, we can also get a sense for how much amniotic fluid is in the womb. It’s a chance to talk about hydration and salt. Parents are invited to listen to their baby’s heartbeat with a fetoscope, and depending on the position of the placenta, they may be treated to the sounds of its ‘whooshing’ as blood flows through the maternal side.

A fetoscope is non-invasive and listens to the baby’s heartbeat and the placenta

Through gentle palpation, we can invite the baby to adjust their position to make it easier on mummy. Perhaps a poking foot is feeling like it’s about to break mummy’s rib. Or little one hasn’t started the descent down into the pelvis as it gets closer to term. Having a simple conversation with the little one and explaining how they can help has shown over and over that these precious babies are sentient and love their mothers and want to participate in a loving and safe arrival.

And to conclude the palpation, I thank the baby for allowing me to play with them.

This gentle approach has brought many mothers to tears. For many of them, it’s the first time their body and their baby have been treated with reverence. In fact, I too, have often been brought to tears by the enthusiastic response of these precious babies who quickly understand that I care deeply about them.

Modern maternity services are decidedly centred around the practitioner. The manoeuvres designed to gather information help the practitioner to determine a course of action that lessens the potential for an obstetrically-determined negative outcome. However, truly client-centred and family-centred maternity care includes the baby as a fully sentient member of the family who deserves as much care, caution, respect, and dignity as every other member of the family. And that’s where we see some of the best outcomes!

Much love,

Mother Billie

©Billie Harrigan Consulting

Endnote

1. Ashrafganjooei, T., Naderi, T., Eshrati, B., & Babapoor, N. (2010). Accuracy of ultrasound, clinical and maternal estimates of birth weight in term women. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 16 (3), 313-317, 2010.

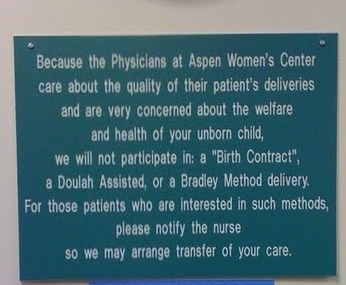

Appeasing the Patriarchy

Recently, the Association of Ontario Doulas (AOD) released their Statement of Position on Non-Aboriginal Traditional Birth Attendant/Companion (TBC) (January 15, 2024) that you can read by following this link.

Since it is a position that is directed at my work in creating and defining the role of a traditional birth companion, it warrants a response.

Content note: This Statement of Position uses sex-based language. The word ‘women’ is used in its historical and traditional context to mean that half of our species that arrives with the biological potential to ovulate, menstruate, conceive, gestate, birth, and lactate. By continuing to read this post you agree to be entirely responsible for your own reactions and your emotional, psychological, and intellectual well-being and hold us free from liability for use of this word.

Billie: of the family Harrigan, elder and companion, Statement of Position re: the Association of Ontario Doulas’ Statement of Position on Non-Aboriginal Traditional Birth Attendant/Companion (TBC)

Whereas the Association of Ontario Doulas (AOD) has released their statement of position regarding non-aboriginal traditional birth attendants/companions that directly misrepresents this emerging sovereign alternative that is spearheaded by me and my efforts, I, Billie: of the family Harrigan offer my commentary and position on their position.

It arrives unsurprisingly, and reads as submissive pandering to existing patriarchal power structures that are both collapsing and increasingly detrimental to the wellbeing of the women who use these services and their babies. It’s filled with innuendo and suggestion that is perhaps meant to intimidate their members into ongoing conformity and obedience.

Since I am the one who has created the unique role of a traditional birth companion in Canada and beyond and I am the one who gave it that name, I am the one who defines it. Not the AOD. Their misrepresentation of my work is stunning. However, it may fit with my hypothesis that the doula profession is limited in its maturation by their alarmingly high and early burnout. Wisdom and insight require time and perseverance.

Prior to the push to move women into hospitals after WW2, it was the tradition in Canada for most women to simply call the neighbour who had some birth skills and experience. This neighbourly support did not include the medical surveillance and interventions associated with modern midwifery. Traditional birth attending or companioning did not have the tools nor the religious-like zeal to engage in today’s fear-based management of a common physiological experience.

Whilst a TBA has “historically referred to indigenous midwives, lay midwives, and community midwives”, a TBC is an invention of mine based on my own 40 years of experience as a companion (as I define it) and my work as an academic specialising in maternity care. Further, traditional midwifery, as that which was practiced prior to the fairly recent medicalisation of childbirth, in no way resembled what passes for midwifery today. The AOD is conflating practices from different eras by using ‘historical’ to define this role and inserting modern medical regulation & practices to suggest they are operating in tandem.

The historical role of the TBA has been largely eliminated by that great coloniser, the WHO and its unholy alliance with pharma and their money in favour of the western medical model as created by Rockefeller and Carnegie. Actual traditional practices have been replaced with modern interventions based on our current cultural belief in the supposed perils of women’s physiology. To suggest a TBC engages in these modern medical practices, as opposed to historical (traditional), non-medical, and un-controlled offerings is to incite division through misrepresentation.

Their statement included the medical industry’s response to women’s choices to leave these services. It’s expected that any industry with a monopoly that is losing control will come out with some statement about how their former customers are being foolish or dangerous. It’s just another example of their suffocating paternalism. The AOD would benefit from reflecting carefully on why they too participated in this paternalism.

It was a curious statement that licensed medical practitioners “are the only ones authorized to ‘practice spontaneous childbirth’” as women all over the earth are releasing their babies in a practice of spontaneous childbirth without any authorisation whatsoever.

It should be noted and carefully understood that the “risk that child welfare organisations may investigate” comes ONLY from another human who calls this agency for an investigation. This human is overwhelmingly a licensed medical practitioner who takes exception that the customer, who arrives to access their services, did not use their services prior to needing their services. It’s a well-documented terror tactic in the realm of obstetric violence that is designed to send a message that families will be punished for non-compliance. It comes from deeply rooted medical narcissism, cult-like behaviour and belief in their offerings, and a complete absence of trauma-informed training or skills. It behoves the AOD to take a firm stand against this heinous practice and advocate for families rather than including it as a threat to families who may not acquiesce to medical control over their family decisions. This omission alone disqualifies the AOD from having a voice for medical autonomy in Ontario.

The AOD’s insinuation or assumption that a TBC “manages labour or conducts the delivery of a baby” in contravention to the Controlled Act is an example of organisational ignorance, as no one has actually contacted me to find out what we do. Further, it’s inflammatory and fuels a political agenda that isn’t about women’s health outcomes but rather the AOD’s hopes for a regulated role within Ontario’s massive medical infrastructure.

Their inclusion of “there have been a number of serious incidents, including a death, in which the birther has chosen a non-Indigenous Traditional Birth Attendant/Companion” takes a page from the technocratic medicalised birth services industry’s playbook that excessively threatens their clients with a dead baby or a dead mother to gain acquiescence in lieu of informed consent or refusal. It was an abhorrent attempt to implicate non-regulated companions as being directly responsible for an adverse outcome. Given the extreme circumstances of the last few years, there have been an exorbitant number of serious incidents and deaths. And yet, there was no mention of the rate of adverse outcomes or deaths in the presence of regulated practitioners. The AOD can no longer claim any moral high ground when it comes to denouncing this tactic to bypass consent. They have learned how easy it is to play the ‘dead baby/mother’ card.

It's important to address their vague threat that “Legal entities may confuse individuals operating in this capacity as people working as unlicensed healthcare providers” along with mention of fines and detention. This confusion could be easily eliminated by careful statements that speak the truth. There is no confusion when the role of a TBC, as I have created it, is represented truthfully and accurately.

Their statement declares that “some” Indigenous communities reserve the use of the word “traditional”. Whilst this may be so for some communities, there is no consensus within the English language that limits its use to aboriginal peoples. Instead, it has a broad understanding to mean things that are not new, typical or normal for someone or something, or doing something for a long time for a particular group. The AOD has misappropriated the historical TBA and the current TBC into their political ideology that is an affront to both.

Modern technocratic medical maternity services are the result and technological iteration of Rockefeller medicine that gained a monopoly through the fraudulent Flexner report and oil money. Safer and saner alternatives exist and could be accessed by more families. However, existing power structures enjoy a monopoly and will not yield to women’s sovereignty and their alternatives. The AOD has come out firmly on the side of existing power structures in spite of their devastatingly high adverse outcomes, trauma, and postpartum suicide as a leading cause of maternal mortality. Their allegiance is with historical patriarchy, medical paternalism, and the ongoing bondage of women in childbirth to a medical model that will not change despite any delusion that they will work together with doulas to improve maternal care outcomes.

In fact, if there’s any lingering confusion about the actual position of the AOD, consider that they put out a call for snitches. The witch hunts never did end.

Despite statements like this from organisations who appear to want to appease oppressive systems for potential recognition or ‘credibility’, the real work to improve maternal outcomes is being done by ordinary women who opt for safer solutions so that more babies arrive safely and gently from healthy, empowered, and non-traumatised mothers. They are becoming more useful humans. The AOD misrepresents my work for political gain, but the women carry on. As we always have.

The system isn’t broken - but its people are

One third of birthing parents has a traumatic birth.

“The system is broken.”

One in 8 new parents enters parenthood with postpartum PTSD from the experience.

“The system is broken.”

Depending on where you live, one third, one half, or almost everyone has a surgical birth.

“The system is broken.”

One in 6 women are abused during their births.

“The system is broken.”

If we say it enough, we might believe it. However, the “system” is decidedly NOT broken. It is doing exactly what it was set up to do by any means available to it.

One third of birthing parents has a traumatic birth.[i] [ii] [iii]

“The system is broken.”

One in 8 new parents enters parenthood with postpartum PTSD from the experience.[iv]

“The system is broken.”

Depending on where you live, one third, one half, or almost everyone has a surgical birth.[v]

“The system is broken.”

One in 6 women are abused during their births.[vi]

“The system is broken.”

If we say it enough, we might believe it. However, the “system” is decidedly NOT broken. It is doing exactly what it was set up to do by any means available to it.

The “system” is how we deliver maternity services. It began when male-midwives, those physicians who broke social etiquette, began attending women in birth. They were barbaric in means because they were sanctioned by the Catholic church to carry sharp instruments that women were forbidden to use. Male barber-surgeons, the Chamberlains, invented the forceps but kept their secret hidden for a century. A few centuries of witch hunts where midwives and female healers were persecuted and executed taught the public to shy away from learning these skills – if they were women. The collusion of religion and medicine ensured that men gained and maintained a monopoly over sick care and what women were allowed to do with their own bodies.[vii]

Eventually, through clever marketing, the male midwife became the preferred attendant as they were considered superior in intellect.[viii] [ix] Women were forbidden to attend universities, practice medicine, or serve in leadership in religions that ruled the western politic, thus unable to influence how women were treated in childbirth.[x]

Sure enough, these clever men discovered how much more profitable it was to bring birthing clients to them rather than going out to their homes.[xi] And so emerged the ‘lying-in’ hospital. The wholesale slaughter of women in these death traps was on par with the witch hunts of a few centuries prior. One in ten women died from puerperal fever, brought on by the unwashed hands of physicians who went from cadaver to the birthing vagina.[xii] Despite the protests of the offensive Semmelweis to wash their hands, ego and elitism prevented them from adopting this simple strategy for many more years thus ensuring the needless deaths of countless more women.[xiii]

Ignaz Semmelweis washing hands with chlorine-water, 1846

Once chloroform and other means of anesthesia were available for use in childbirth, the medical societies lobbied the government to grant them exclusive access. Not that they were any more qualified to use these powerful drugs than any other discipline, they merely had the ear of those in power who made these decisions.[xiv] Next followed the most effective smear campaign in all of history to drive midwives and alternative healing modalities out of business. [xv] [xvi] By the end of WW2 the campaign was almost complete. Next came effective lobbying to ensure governments were only favourable to their approach and the money, legislations, and endorsements flowed to hospital based technocratic birth where the obstetrician is royalty.

Even today, midwives around the world are persecuted and legislated out of business for offering client-centred care and serving women outside of hospitals.

Leaning heavily on Henry Ford’s conveyor belt system of turning out cars, optimisations and standardisations were implemented to cut costs, increase revenue, and turn the business of birth into a well-oiled machine.[xvii]

What we have is an effective system of profit for those industry players who set it up this way.

Of course, women are abused in birth! It’s an effective means of getting them to submit to a routine, one-size-fits-all, conveyor belt, in-and-out, profitable baby factory.

Even the current schedule of prenatal visits has no basis in science, evidence, or benefit. It was created by those same male-midwives who took a good thing and made it $tandard. Certainly, diagnosing and treating medical issues is an important healthcare strategy, whether pregnant or not. In light of the evidence that today’s current schedule and routines have not produced the promised results of healthier pregnancies or births, the industry recommended and implemented a strategy to convince the public that the process of pregnancy could not be trusted to stay normal without their surveillance.[xviii]

Now let’s talk about the people.

Some people enter this industry because it’s proven itself as a profitable endeavour. Obstetrics includes a great deal of power and control over a physiological process that in most cases would unfold quite simply without them. This appeals to some people. It’s a position of elitism and sits higher on the social hierarchy. There’s nothing to see there. Nothing to reach. Nothing to change.

And some enter this industry because they believe they have something valuable to offer during one of the most sacred and vulnerable times in a person’s life. They believe in the importance of how new humans are greeted into this world.

But because they have entered a highly successful system, they witness and sometimes participate in horrific abuses of mothers and babies. Some are broken by this and are the walking and working wounded, grappling with trauma, burnout, PTSD, and even suicidal ideation. Some survive and continue doing the best they can without the learned skillset of trauma-informed care that protects them and their clients. And some become part of the system of abuse and profit as their initial purpose is co-opted by internalised patriarchy and misogyny.

But what’s to be done with those who are broken and those who are merely surviving? The system doesn’t care if they burnout and leave. Players are easily replaced by new inductees at beginner salaries. It was never set up to take care of anyone. It was set up as a profitable means of co-opting physiology for profit based on fear and coercion.

“What we have is a medical system that is literally killing people through suicide.”

Break time. Nature and birth are not always kind. Women have always benefited from the companionship and knowledge of their midwives. And when events became problematic, skilled surgeons and expert paediatricians have brought hope and life where there was once only death. This post only speaks to the system of facility-based birth that currently exists within a patriarchal, misogynistic, and technocratic paradigm.

Back to the people.

‘Burnout’ consists of three features

Emotional exhaustion – feeling emotionally depleted from being overworked