Why I don't do vaginal exams ~ Wisdom from a Traditional Birth Companion

I let my new client know what would happen when I arrived at her home when she was in labour. We talked about sanitation measures, spending time in the kitchen, setting up the pool, and where I could take a nap if she needed some privacy. I said I would not be doing any vaginal exams as I think they’re rude, and she wept with relief.

I specialise in trauma and the majority of my clients are refugees from the medical system, running from ritual abuse and routines that protect the industry. They want someone to mentor them through to a healthy birth without the traps and trappings of the industry that removed their choice, and violated their autonomy and their dignity.

As a traditional birth attendant, I don’t do vaginal exams.

I was talking with my new client about what would likely happen when I arrived at her home when she was in labour. We talked about sanitation measures, spending time in the kitchen, setting up the pool, and where I could take a nap if she needed some privacy. I said I would not be doing any vaginal exams as I think they’re rude, and she wept with relief.

I specialise in trauma and the majority of my clients are refugees from the medical system, running from ritual abuse and routines that protect the industry. They want someone to mentor them through to a healthy birth without the traps and trappings of the industry that removed their choice, and violated their autonomy and their dignity.

We won’t go into the history of obstetrics that began with the burning of witches (midwives and healers), the rise of the man-midwife, the development of lying-in hospitals, and eventually the wholesale co-opting and medicalisation of birth. Suffice it to say that obstetrics and hospitalisation didn’t “save” women and babies (1). It created untold harm and mortality until they learned better infection control and saner behaviours. Today, it’s still leaving a trail of destruction as about 1/3 of their clients are traumatised (2,3,4) and about 1 in 8 enter parenthood with postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder (5,6,7). Suicide is a leading cause of maternal death in the first year and is highly correlated to trauma (8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16). It’s an industry out of control with unjustifiable caesarean rates, dangerous inductions for spurious reasons, and wholesale overuse of medications and interventions.

What women didn’t notice in this process of medicalisation and co-opting of their physiology for profit is that the medical industry took ownership of their vaginas once they became pregnant. Pregnancy transfers ownership of the vagina from the woman to the industry. Midwifery and obstetrical regulations stipulate that inserting an instrument, hand, or finger beyond the labia majora is a restricted practice sanctioned by legislation (17). To test this, see how long it takes for someone in the industry to file a Cease and Desist or start a campaign of persecution for the purpose of prosecution if they catch wind of anyone but one of their own sticking their fingers up there. No one but an insider sticks their fingers into their territory. It doesn’t matter who the mother gives her permission and consent to - it must be a member of the priesthood of modern medicine.

Of course, in their benevolence, they’re generally quite accommodating where partners are concerned, because most partners are male and obstetrics is exceedingly misogynistic. They value the needs and the pleasures of the D.

As a traditional birth attendant, I don’t do vaginal exams. For one thing, it’s considered a restricted practice for just the medical pundits and not doing them with my clients keeps the industry players somewhat placated knowing I’m not intruding into their turf. But the real reason is because I think they’re completely unnecessary and wouldn’t do them even if the medical folks begged me to under the guise that it would make birth safer.

To better understand the offence of the routine vaginal exam, we have to go back in time to when the male-midwife moved into the sanctity of women-centred birth and the domain of the midwife. It was profitable. And they convinced the public that they would provide a superior service based on the cultural belief of the time that women were disadvantaged by an inferior intellect and a predilection for sorcery (18,19). They also brought with them the medical perspective that women were an error of nature and that the world, and thus its inhabitants, were but a machine that could be best understood by coming to know its parts in isolation of the whole.

And so began dissection, mechanisation, and reducing birthing women to their parts. She became a womb expelling a foetus through a vagina. Think of today’s obstetrical “power, passenger, passage” perspective on how birth unfolds. Not much has changed in 400 years.

By sticking their fingers up there, they discovered that the cervix opens to expel the foetus. Oh, happy day! From the morgue to the birth suite, physician fingers were poking everything. Throughout the early and mid 1800’s, the infection rate in some hospitals soared as high as 60% from the mysterious childbed fever, with death rates as high as 1 in 4 (20). Nothing the doctors did was contributing to this mystery as physicians were gentlemen and gentlemen didn’t carry germs (21). And once they did accept that their filthy practices were killing women, rather than abandon the idiocy of penetrating their patients in labour, they eventually figured out how to make it less dangerous.

The practice of obstetrics has always been highly resistant to change and common sense. After all, they’ve had 400 years to figure things out and women are still birthing on their backs!

Once it was discovered that the cervix dilates as part of the labouring process, the medical industry has been fixated on that bit of tissue and made it the focus of their entire assembly line drive-through everyone-gets-what’s-on-the-menu service. That bit of tissue determines how the ward allocates services, whether the client will be permitted to stay, and how long she’ll be allowed to use their services before the next client needs the bed.

Thanks to Dr. Emanuel Friedman, who examined the cervices of 500 sedated first-time mothers in the 1950’s and plotted their dilation on a graph and matched it to the time of their birth – we now have the infamous Friedman’s Curve and the partogram.

© Evidence Based Birth

The partogram is a graph that plots cervical dilation and descent of the foetal head against a time-line. When the graph indicates that progress is slower than is allowable according to the particular chart chosen by their institution, then the practitioner is called upon to administer various interventions to speed things up to keep the labour progressing well, aka, profitably. Should these acceleration measures fail to produce a baby in a timely manner or cause foetal distress, then a caesarean section is the solution. “Failure to progress”, and the accompanying foetal distress that is often a consequence of those acceleration measures, are the leading causes of a primary caesarean (22).

Obstetrical partogram

In addition to clearing the bed for the next client, obstetrics has another reason for expediting labour. The more vaginal exams a woman receives, the greater the likelihood she’ll develop a uterine infection (23). So, once they start the poking, they need to get the baby out before their prodding adds another problem for them to solve.

In the absence of a medical situation, routine vaginal exams in labour are for the purpose of charting in order to maintain a medicalised standard of modern technocratic birth.

A labouring client will not be admitted to a hospital without a vaginal exam to determine if her dilation is far enough along for their services (unless she’s clearly pushing). And this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Early admission to the hospital results in more interventions and more caesareans than later admission (24). This is a business and time is money.

A regulated midwife attending a homebirth will likewise perform a vaginal exam upon arrival at the client’s home to determine if the client is far enough along to warrant their limited resources and time by staying and beginning the partogram or leaving and waiting to be called back later. They must also follow the rules of the hospital at which they have privileges or their regulatory agency and transport for augmentation/acceleration if the partogram shows a significant variation.

All of this is predicated on the outdated and obsolete notion that women are machines and birth is a linear process. The only thing a vaginal exam reveals is where the cervix is sitting at that particular moment and how it’s interpreted by that particular practitioner. Women are not machines and birth is not linear. Just like any mammal, birth can be slowed, stopped, or sabotaged by an unfavourable environment or reckless attendants. I’ve said for years that it’s so easy to sabotage a good birth, it’s embarrassing.

“Years ago, I was with a first-time mother planning a family-centred homebirth. She was on the clock and had a deadline. At 42 weeks gestation, she had until midnight that night to produce a baby in order to have a midwife-attended homebirth. After that, she was expected to report to the hospital for a chemical induction. As her contractions built throughout the day, her preferred midwife arrived and labour was progressing well. She was enjoying the process and the camaraderie of her sisters-in-birth. Eventually, one of the vaginal exams revealed a cervical dilation of 8 cm, indicating it was time to call in the 2nd midwife. Only, it was a midwife that had routinely upset the mother throughout pregnancy with requests for various tests and talk of all the dangers of declining routine testing. Upon learning this midwife was coming to the birth, labour slowed.

Soon enough, the 2nd midwife arrived and assumed authority over the birth process and insisted on repeated vaginal exams for the purpose of staying within the parameters of the partogram. Her vaginal exams were excruciating, no doubt because she was trying to administer a non-consenting membrane stripping as an intervention to address the slowed and almost non-existent contractions. Eventually, an exam revealed a dilation of only 6 cm. After several more hours of “torture” (according to this mother’s recount) to keep labour going rather than just leaving the mother to rest and accepting that this labour had been hijacked and needed time to regroup and restart, dilation regressed to 4 cm and the mother eventually ended up acquiescing to a hospital transfer, and experienced an all-the-bells-and-whistles birth, trauma, and postpartum PTSD.

This mother’s subsequent birth a couple of years later didn’t include inviting midwives and unfolded as it was meant to. After a day of productive and progressing labour that was clearly evident without sticking fingers up her vagina, she eventually got tired and labour slowed and stopped. She went to bed and I went home. When she woke up, labour resumed and a baby emerged swiftly and joyously. As it turns out, for her, she has a baby after a good sleep with people she trusts.”

What about the routine vaginal exams in late pregnancy? Glad you asked!

Since they don’t have good predictive value, meaning they won’t diagnose when labour will begin, how long it will take, or whether the woman’s pelvis will accommodate that particular baby prior to labour, they have 2 functions.

The first is to plan and initiate your induction.

A cervical exam provides information that is measured against a Bishop Score. A Bishop Score provides a predictive assessment on whether an induction is likely to result in a vaginal birth or is more likely to result in a caesarean for “failure to progress”. A cervix that scores higher is more likely to respond to an induction whereas a lower score indicates a less favourable outcome (25). Further, a vaginal exam allows the practitioner to begin the induction process with a membrane stripping/stretch-and-sweep.

The second purpose for routine vaginal exams in pregnancy is to build in sexual submission. It reaffirms the power dynamic where someone who is not the woman’s intimate sexual partner is allowed to penetrate her genitals at will. It makes their job much simpler once she’s is in labour. She has been trained to accept this violation.

A vaginal exam during labour might rarely be indicated when there is a problem that requires more information. A vaginal exam can help determine if there’s a possible cord prolapse requiring immediate medical attention, or can asses the position and descent of the baby to help suggest strategies to encourage the baby to move into a better position. However, when a labour is spontaneous, meaning it hasn’t been induced by any mechanical, chemical, or “natural” means, the labour isn’t augmented with artificial rupture of membranes or synthetic oxytocin, and the labouring woman is untethered and free to move as her body indicates, complications are far less likely.

Throughout my 35 years in supporting birthing families, I can say that babies do indeed come safely and spontaneously out of vaginas when there’s no one sticking their fingers up there. And they tend to come more quickly. Routine vaginal exams don’t contribute to the safety of the mother/baby. However, they do add to the safety of the practitioner who is tasked with placating the technocratic gods who demand they follow protocols and keep the wheels of the business running on track.

My reasons for not doing vaginal exams, even if the the technocratic gods gave their blessing, include:

They’re rude

They’re unnecessary

They shift the locus of power from the birthing woman to the person with the gloves

They introduce the potential for infection

They interrupt labour and can sabotage a good birth

They often hurt

They can traumatise the cervix

They can traumatise the mother

They can impact the experience of the baby

There are so many simpler ways to determine how labour is progressing

I don’t practice medicine or midwifery or engage in its absurdities

I really am not that interested in other people’s vaginas

Let’s talk about when labour does veer from a normal physiological process.

When the power dynamic places the labouring and birthing mother in charge of the experience, it actually becomes a safer and simpler process. She is the one who is experiencing the labour and birth and is the one relaying information. Only she is in direct communication with her baby. She is the one who knows when labour has exceeded her resources and she needs medical help, pharmacologic pain relief, or the reassurance of the technocratic model.

Of course, not all births unfold simply. However, my experience over these many years is that when women are not expected to submit to exams for the purpose of charting and the subsequent limitations imposed by those charts, birth unfolds a lot more simply far more often.

Much love,

Mother Billie ❤️

Endnotes

Tew, Marjorie. Safer childbirth?: a critical history of maternity care. (2013). Springer.

Garthus-Niegel, S., von Soest, T., Vollrath, M. E., & Eberhard-Gran, M. (2013). The impact of subjective birth experiences on post-traumatic stress symptoms: a longitudinal study. Archives of women's mental health, 16(1), 1-10.

Creedy, D. K., Shochet, I. M., & Horsfall, J. (2000). Childbirth and the development of acute trauma symptoms: incidence and contributing factors. Birth, 27(2), 104-111.

Schwab, W., Marth, C., & Bergant, A. M. (2012). Post-traumatic stress disorder post partum. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde, 72(01), 56-63.

Montmasson, H., Bertrand, P., Perrotin, F., & El-Hage, W. (2012). Predictors of postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder in primiparous mothers. Journal de gynecologie, obstetrique et biologie de la reproduction, 41(6), 553-560.

Beck, C. T., Gable, R. K., Sakala, C., & Declercq, E. R. (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder in new mothers: Results from a two‐stage US National Survey. Birth, 38(3), 216-227.

Shaban, Z., Dolatian, M., Shams, J., Alavi-Majd, H., Mahmoodi, Z., & Sajjadi, H. (2013). Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following childbirth: prevalence and contributing factors. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 15(3), 177-182.

Oates, M. (2003). Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. British medical bulletin, 67(1), 219-229.

Oates, M. (2003). Suicide: the leading cause of maternal death. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 183(4), 279-281.

Cantwell, R., Clutton-Brock, T., Cooper, G., Dawson, A., Drife, J., Garrod, D., Harper, A., Hulbert, D., Lucas, S., McClure, J. and Millward-Sadler, H. (2011). Saving Mothers' Lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006-2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology, 118, 1-203.

Austin, M. P., Kildea, S., & Sullivan, E. (2007). Maternal mortality and psychiatric morbidity in the perinatal period: challenges and opportunities for prevention in the Australian setting. Medical Journal of Australia, 186(7), 364-367

Palladino, C. L., Singh, V., Campbell, J., Flynn, H., & Gold, K. (2011). Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Obstetrics and gynecology, 118(5), 1056.

Grigoriadis, S., Wilton, A.S., Kurdyak, P.A., Rhodes, A.E., VonderPorten, E.H., Levitt, A., Cheung, A. and Vigod, S.N. (2017). Perinatal suicide in Ontario, Canada: a 15-year population-based study. Cmaj, 189(34), E1085-E1092.

CEMD (Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths) (2001) Why Mothers Die 1997–1999. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

Sareen, J., Cox, B. J., Stein, M. B., Afifi, T. O., Fleet, C., & Asmundson, G. J. (2007). Physical and mental comorbidity, disability, and suicidal behavior associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in a large community sample. Psychosomatic medicine, 69(3), 242-248.

Hudenko, William, Homaifar, Beeta, and Wortzel, Hal. (July 2016). The Relationship Between PTSD and Suicide. PTSD: National Center for PTSD, U.S. Department of Veterans Affair.

Act, Ontario Midwifery. "SO 1991, c. 31." (1991).

Smith Adams, K. L. (1988). From 'the help of grave and modest women' to 'the care of men of sense': the transition from female midwifery to male obstetrics in early modern England. (Master’s thesis, Portland State University.

Burrows, E. G., & Wallace, M. (1998). Gotham: a history of New York City to 1898. Oxford University Press.

Semmelweis, I. (1983). Etiology, concept, and prophylaxis of childbed fever. Carter KC, ed. Madison, WI.

Halberg, F., Smith, H. N., Cornélissen, G., Delmore, P., Schwartzkopff, O., & International BIOCOS Group. (2000). Hurdles to asepsis, universal literacy and chronobiology-all to be overcome. Neuroendocrinology Letters, 21(2), 145-160.

Caughey, A. B., Cahill, A. G., Guise, J. M., Rouse, D. J., & American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2014). Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 210(3), 179-193.

Curtin, W. M., Katzman, P. J., Florescue, H., Metlay, L. A., & Ural, S. H. (2015). Intrapartum fever, epidural analgesia and histologic chorioamnionitis. Journal of Perinatology, 35(6), 396-400.

Kauffman, E., Souter, V. L., Katon, J. G., & Sitcov, K. (2016). Cervical dilation on admission in term spontaneous labor and maternal and newborn outcomes. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 127(3), 481-488.

Vrouenraets, F. P., Roumen, F. J., Dehing, C. J., Van den Akker, E. S., Aarts, M. J., & Scheve, E. J. (2005). Bishop score and risk of cesarean delivery after induction of labor in nulliparous women. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 105(4), 690-697.

Beyond the Shot: Preventing Postpartum Haemorrhage ~ Wisdom from a Traditional Birth Companion

Postpartum haemorrhage is a complication that can happen in any birth setting, although it’s more likely in a hospital. Despite the universal application of “active management” as a prevention, the rate of haemorrhage due to uterine atony has been steadily climbing in developed nations.

“Active management of the 3rd stage”, is an intervention for the birth of the placenta, the time when women are most likely to lose a significant amount of blood. It involves injecting the mother with a uterotonic (something to make the uterus contract), usually synthetic oxytocin, as soon as the baby is born, and it may include some other steps like early cord clamping or pulling on the umbilical cord depending on the protocol used. This intervention is applied to all birthing women in all hospitals, birth centres, and homes with few exceptions.

You’d think if every mother everywhere gets this injection, then it must be a good thing. Well, that’s the thing about obstetrics. It tends to take an intervention that might be suitable for some clients in certain situations and applies it to everyone. And the results are increasingly worrisome.

© Billie Harrigan Consulting

“We don’t birth according to the science. We birth according to what we believe.

And we don’t believe the science.”

~ Mother Billie

Hospital-based birth presents some unique safety challenges. Over the years, there have been various efforts to reduce the increased risks. Some of them have been successful, such as hand washing and sanitation to reduce infections, and some of them not at all successful, such as any attempt to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections.

Postpartum haemorrhage is a complication that can happen in any birth setting, although it’s more likely in a hospital (1,2,3,4). Despite the universal application of “active management” as a prevention, the rate of haemorrhage due to uterine atony has been steadily climbing in developed nations (5,6,7,8).

“Active management of the 3rd stage”, is an intervention for the birth of the placenta, the time when women are most likely to lose a significant amount of blood. It involves injecting the mother with a uterotonic (something to make the uterus contract), usually synthetic oxytocin, as soon as the baby is born, and it may include some other steps like early cord clamping or pulling on the umbilical cord depending on the protocol used. This intervention is applied to all birthing women in all hospitals, birth centres, and homes with few exceptions.

You’d think if every mother everywhere gets this injection, then it must be a good thing. Well, that’s the thing about obstetrics. It tends to take an intervention that might be suitable for some clients in certain situations and applies it to everyone. And the results are increasingly worrisome.

To begin – what is a postpartum haemorrhage?

The general definition of postpartum haemorrhage is blood loss of 500mls in the first 24 hours following a vaginal birth, or blood loss of 1000mls following caesarean surgery. A severe postpartum haemorrhage is loss of 1000mls after a vaginal birth (or 1500mls in some locations).

The first question we need to ask is why 500mls was chosen as the threshold for defining a haemorrhage? When no uterotonics are used and postpartum blood loss is measured, the average blood loss in the first hours is actually around 500mls (9,10). Estimating blood loss by looking at it is fairly inaccurate and most observers tend to underestimate blood loss (11,12,13). This means that healthy births that look like they didn’t release much blood have actually released about 500mls in the first hours, which is technically a haemorrhage.

Since 500mls has been selected as the threshold for haemorrhage, the effectiveness of every intervention is based on its ability to reduce the average amount of blood a woman releases in the first hours after birth, because now average is considered pathological.

If we move away from pathologising average amounts of blood, then a new definition of postpartum haemorrhage might be considered. A haemorrhage could be considered as any blood loss that exceeds that mother’s physiological capacity to accommodate it without any accompanying morbidity.

For a mother with adequate iron stores and a healthy blood volume expansion, which is about 1450mls of additional circulating blood, a loss of over 500mls may present no additional challenges. In fact, most women who experience a blood loss of over 500mls receive no clinical intervention or experience any serious consequences (14,15,16). And yet, for a mother who has had a challenging pregnancy or other health concerns, with poor blood volume expansion and exhausted iron stores, a loss of much less might present difficulties and require treatment.

It’s hard to get estimates on the prevalence of postpartum haemorrhages as there are profound differences in reported outcomes from different countries, facilities, and clientele (17). This tells us there are significant differences in how blood loss is measured, the health of the clientele, and what is done to the birthing client that either improves or exacerbates bleeding. And because women are not standardised machines, there is tremendous variability between individuals.

Why does it happen?

About 80% of the time, a postpartum haemorrhage is the result of uterine atony, which is a lack of effective contractions (5,18). Without effective contractions, the blood vessels behind the placenta fail to close and blood continues to flow freely. It can also be caused by physical trauma, for example lacerations in the vagina or cervix from tearing, forceps, or an episiotomy. Uterine rupture can cause a haemorrhage, as can a placental abruption, where the placenta prematurely separates from the uterine wall. Retained placental tissue or blood clotting disorders in the mother can also cause a haemorrhage.

Active management to the rescue!

Active management only addresses uterine atony. It can’t help when the reason for the haemorrhage is physical trauma from tearing or cutting, or address a blood clotting disorder. The World Health Organisation and most medical and midwifery associations recommend giving 100% of women an injection of synthetic oxytocin just after the baby arrives as a means of preventing postpartum haemorrhage (19). Oxytocin is a naturally occurring hormone that causes the uterus to contract. It’s the primary hormone of labour. An injection of 10IU of synthetic oxytocin, either intramuscular or added to an IV, is the recommended intervention. In low resource settings where there is no synthetic oxytocin, which requires stable temperature and a skilled attendant to administer it, then an oral dose of misoprostol is recommended as a preventive.

REX/Shutterstock

What about that shot of synthetic oxytocin?

Synthetic oxytocin is a drug that is marketed under the brand names Pitocin, Syntocinon, and a number of lesser-known brands. It’s a clear aqueous solution that contains a chemically identical synthetic version of naturally-occurring oxytocin. Naturally-occurring oxytocin is produced in the brain by the hypothalamus and released both as a neurotransmitter across the brain facilitating feelings of love, bonding, trust, empathy, and compassion, and as a hormone through the posterior pituitary gland into the blood where it acts on smooth muscles in pulses or waves. Synthetic oxytocin is delivered through a syringe into the mother’s muscle (usually the thigh or bum) or through an IV directly into the blood stream. It does not cross the mother’s blood-brain barrier and doesn’t support bonding with the baby.

Looking at Pitocin, we see that it also contains 0.5% Chlorobutanol, a chloroform derivative as a preservative, acetic acid to adjust its pH, and may contain up to 16% of total impurities (20).

When given as an injection, the uterus responds by contracting within 3-5 minutes and lasts for 2-3 hours. When given in an IV, the uterus responds almost immediately and it lasts about an hour. It’s removed from maternal plasma through the liver and kidneys.

Just like any drug, synthetic oxytocin comes with risks, including

Anaphylactic reaction – an allergic reaction where the individual may stop breathing

Uterine hypertonicity, spasm, or tetanic contraction

Uterine rupture

Premature ventricular contractions – feels like heart palpitations or the heart is “skipping a beat”

Pelvic haematoma – a blood clot similar to a deep bruise

Hypertensive episodes – spiking blood pressure

Cardiac arrhythmia – fluctuations in heartbeat

Nausea and vomiting

Headache, loss of memory, confusion

Loss of coordination, fainting

Seizures

Subarachnoid haemorrhage – bleeding beneath the membrane that covers the brain. This can lead to stroke, seizures, brain damage, and death

Fatal afibrinogenemia – an absence of fibrinogen circulating in the blood which is needed for blood clotting. This leads to sudden and uncontrollable haemorrhage until death

Postpartum haemorrhage

Prolonged bleeding in the days and weeks after birth

“The possibility of increased blood loss and afibrinogenemia should be kept in mind when administering the drug.” ~ drugs.com

The preservative Chlorobutanol has a half-life of 10 days and is anti-diuretic, meaning it will interfere with normal elimination for up to 10 days and may contribute to increased breast engorgement. An allergic reaction can cause dermatitis, usually beginning on the face and chest. It is known to cause light headedness, ataxia (loss of coordination, speech, or eye movement), and nightmares.

Does this intervention work?

The most recent Cochrane Review (2019) (17), reveals that this recommendation is based on studies with “very low” to “moderate” level quality. According to the review, using synthetic oxytocin after the birth of the baby

May reduce the risk of blood loss of 500 mL after delivery (low-quality evidence)

May reduce the risk of blood loss of 1000 mL after delivery (low-quality evidence)

Probably reduces the need for additional uterotonics (moderate-level evidence)

May be no difference in the risk of needing a blood transfusion compared to no intervention (low-quality evidence)

May be associated with an increased risk of a third stage greater than 30 minutes (moderate-quality evidence)

An earlier Cochrane Review revealed that it reduces average blood loss by about 80mls (21). This is usually enough to bring the average blood loss below 500mls thereby avoiding a diagnosis of postpartum haemorrhage. When it comes to severe postpartum haemorrhage of over 1000mls blood loss, it only shows a marginal improvement over expectant management (watching and waiting) (17), and it doesn’t lessen the need for blood transfusion (22).

What else does this drug do?

Synthetic oxytocin dramatically increases the incidence of postpartum depression and anxiety in the first year. In women with a history of depression or anxiety, exposure to this drug increases the risk by a whopping 36%, and for women with no history of depression or anxiety, this drug increases the risk by 32% (23).

Synthetic oxytocin is also associated with greater breastfeeding failure and somatisation symptoms (pain with no known organic cause) (24).

Asking the big questions

Is reducing the average amount of blood loss by about 80mls based on an arbitrary threshold of 500mls worth the risks of this intervention? Are there safer ways to reduce the potential for haemorrhage?

Identifying the risks

There are certain factors that increase the potential for haemorrhage. The rising rates of postpartum haemorrhage have been linked to rising rates of induction and augmentation (25). More women with previous caesareans also mean more haemorrhages, possibly because there are more problems with how the placenta inserts itself in the uterus. Twins or polyhydramnios (excessive water) that overly distends the uterus, is a risk factor. As is pre-eclampsia, chorioamnionitis, and obesity (26).

As mentioned before, hospital birth is a significant risk for a haemorrhage of 1000mls or more (1,2,3,4). This isn’t surprising since hospital births include inductions, augmentations, and complicated pregnancies. However, when comparing the same low risk groups, hospital birth is still an independent risk factor. It’s also the place that is most likely to disrupt the physiology of birth with ritual and routine.

And this is where it gets even more interesting. Studies have shown that when comparing active management with physiological management, that jab of synthetic oxytocin can reduce average blood loss by about 80mls. The problem with these studies is that hospital births are not generally places where physiology is understood or supported. Meaning they might be comparing the same management except that one includes a shot and one doesn’t.

For example, early clamping of the umbilical cord became a world-wide intervention based on terrible presumption and continued in light of great research due to entrenched habit and ego. In one study, women who had a “physiological” 3rd stage had greater postpartum haemorrhages over 1000mls compared to actively managed women (27). The authors noted that the more the placenta weighed, the greater the blood loss. And, why did these placentas weigh so much? Because early clamping of the cord was the usual practice. Draining the cord to reduce the blood volume of the placenta reduces haemorrhage (28) and of course that blood belongs in the baby, not a pail on the floor.

Early cord clamping - Getty Images

In a study where midwives were familiar with the normal birth of the placenta and were less likely to disrupt it, active management doubled haemorrhages over 1000mls (29). In another study where the birth of the placenta was supported with “holistic” care, active management increased the risk of haemorrhage by 7-8-fold (30).

Feeding the mother and the uterus

Labour is an intense activity and requires about 1000 calories of energy per hour. Denying mothers food during labour was an attempt in the 1940’s to prevent her from vomiting under general anesthesia and then breathing in the vomit (31). We know that obstetrics is slow to change, after all, they’ve had 400 years to get women off their backs! Most women are still denied food in a hospital. No one is using the anesthesia of the 1940’s. Forced fasting doesn’t prevent vomiting (32), it only makes the mother more miserable and contributes to a longer labour (33). And longer labours are more likely to be augmented, putting the mother at risk for haemorrhage.

Perhaps a hungry uterus is one that doesn’t contract after the birth of the baby. A study that compared the usual shot of synthetic oxytocin in the mum’s bum to giving her some lovely dates to eat after the birth showed that eating dates was more effective in reducing blood loss than the injection (34). I remember discussing this with some traditional midwives who reported the same great results from giving the mother apricot nectar after the birth. Nourishing mothers is just good care.

© Billie Harrigan Consulting

What is this holistic care that makes birth so much safer?

Holistic care acknowledges that we are mammals and need the same conditions as any mammal giving birth. Birth is a time of reconnection where mother and baby’s interdependence moves from womb to arms. Both the mother and the baby have been waiting for this moment to gaze into each other’s eyes and to say “I know you”. Supporting this reconnection is key to ensuring the birth of the placenta unfolds safely.

And we return to oxytocin, the kind our brain produces, to ensure this reconnection is joyous and safe. Oxytocin is the hormone of love, bonding, trust, empathy, and the one that contracts the uterus and ejects the milk. Oxytocin is also the hormone of orgasms. Anything that disrupts a good orgasm is what disrupts the bonding and the expulsion of the placenta.

Oxytocin is easily encouraged, but it’s also easily disrupted.

holistic care

The room is warm, dimly lit, a sanctuary encircling the mother with love and support. She is nourished and feels safe and cared for. Her labour has begun spontaneously, no drugs, no stretch-and-sweep, and no “natural” induction. The hormones of birth are primed and mother and baby are prepared for this transition from womb to arms. Their hearts cry out for each other; their very skin crawling in anticipation of each other’s touch. The mother heeds the calls of her labour and sways, groans, rises, and pushes. The baby emerges with its protective coating of vernix and is colonised by its mother’s flora. The mother’s waiting hands draw her baby up to her chest which has already adjusted its temperature to ensure the baby is kept warm through her own bodily heat and skin-to-skin contact. The baby smells divine! Its head is releasing pheromones drawn in with each of the mother’s breaths. This baby’s scent reaches the olfactory bulb in the limbic system where the amygdala creates a permanent memory of this precious child. The hypothalamus receives the message that the newest member of our humanity is earthside and sends a gush of oxytocin to ensure bonding, preparation for breastfeeding, and a message to the uterus to contract to begin expelling the placenta. As mother and baby continue to explore each other, the placenta is released and mother feels the urge to expel it. She moves freely, adjusting, and rising to use gravity to her advantage again as it falls gently into a bowl. The bowl is placed next to her as there’s no rush to sever the connection between the baby and its placenta until baby is secure in its connection to its mother. Then she rests, with her baby nestled between her breasts, beginning its journey to her nipple to receive the long-awaited nectar. Both are wrapped in a blanket to ensure they are warm and cocooned. A cup of warm sweet tea and a snack is brought to her and she admires her courage, her strength, and her baby at her breast. Her uterus contracts as it is nourished and charged by the suckling of the baby. Her bleeding is much like a heavy period for a few days, then lessens, and is generally finished within 2-3 weeks.

BSIP/Getty Images

usual care

The room is cool and bright, smelling of antiseptic, the shoes of exhausted nurses and midwives, and echoing the cries of others down the hall. The mother is lying on a narrow bed thrashing as the waves hit, unable to get up, run, leave. The belts are wrapped around her belly measuring each wave requiring her to limit her movement to meet their unfeeling demands. She is exposed and hungry with an IV feeding her fluids and keeping an open port in anticipation of an emergency. On her back, her waves are met with instructions to pull back her legs, bow her head, and hold her breath and push to the count of ten as the room fills with strangers, lights point at her vulva, and the appointed one sits between her legs. The resuscitation station has been warmed and primed to receive her newly born baby. The appointed one may choose to cut open her perineum. As the baby emerges, it is received by the appointed one who may also choose to separate the baby from its source of blood and oxygen through careless ritual. The mother is injected with a dangerous drug and the baby is dried. A hat is placed on the baby’s head so the glory of its scent cannot reach the mother’s limbic system to register this new life. The baby may be wrapped up, preventing the benefits of skin-to-skin, including colonising the mother’s flora, regulating its temperature, and preventing postpartum haemorrhage (35). The baby may be placed on its mother’s chest or it may go to the warming station for weighing and injecting. Once on its mother’s chest, strange hands continue to probe, measure, and instruct. In time, there is food. Her bleeding remains heavy for the first 2 weeks and tends to finish by her 6-week postpartum check-up.

Image by Engin Akyurt from Pixabay

But, but … the hat!

Since the placing of hat is a ritual that is often replicated at home, thereby increasing the potential for haemorrhage, let’s talk some more about it.

Newborn babies don’t regulate their body temperature with the same efficiency as adults. They need help in staying warm. However, biology is glorious and rarely needs our routines. The space between the mother’s breasts adjusts its temperature to ensure the baby is kept at the right temperature, even accommodating the different needs of twins (36). This requires skin-to-skin contact. The other regulating factor is the temperature of the room. A warm room keeps the baby warm (37).

It’s believed that because babies have large heads, they are more likely to lose heat through their heads, so putting a hat on it will keep the baby warm. Only it doesn’t. Stockinette hats don’t affect the core temperature of the baby (38,39). Thermal hats do, and they’re an important part of caring for and transporting a vulnerable premature baby. The only thing knitted hats do is prevent the mother from breathing in the baby’s scent and releasing more oxytocin in response. It’s a foolish ritual.

The elements of holistic care:

Wait for spontaneous labour where possible

Freedom of movement throughout labour to avoid a long labour and augmentation

Nourish the mother with food and drink according to her preference

Warmth and privacy

Spontaneous pushing in the mother’s preferred position

No clamping or cutting of the cord until the placenta is birthed

Immediate skin-to-skin

No hat on the baby

Quiet, private, and supported time between mother and baby

Placenta is birthed by maternal effort aided by gravity

Nourishment for the mother soon after the birth

Ongoing comfort, warmth, and autonomy for the mother

Conclusion

Active management appears to be a dubious and somewhat dangerous intervention that was introduced to overcome obstetrics’ lack of understanding of physiology and their pathological need to disrupt it.

When birth is supported with holistic care, it’s up to 7-8 times safer than routine hospital care with the routine jab. Preventing postpartum haemorrhage comes down to understanding and respecting the physiology of birth, the intense need that mothers and babies have for one another, and not getting in the way. And if there’s a problem, then it requires prompt treatment, but not before to cause the problem.

Much love,

Mother Billie

Endnotes

Scarf, V.L., Rossiter, C., Vedam, S., Dahlen, H.G., Ellwood, D., Forster, D., Foureur, M.J., McLachlan, H., Oats, J., Sibbritt, D. & Thornton, C. (2018). Maternal and perinatal outcomes by planned place of birth among women with low-risk pregnancies in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Midwifery, 62, 240-255.

Hutton, E. K., Cappelletti, A., Reitsma, A. H., Simioni, J., Horne, J., McGregor, C., & Ahmed, R. J. (2016). Outcomes associated with planned place of birth among women with low-risk pregnancies. Cmaj, 188(5), E80-E90.

Blixa, E., Huitfeldtb, A. S., Øiand, P., Straumea, B., & Kumle, M. (2014). Outcomes of planned home births and planned hospital births in low-risk women in Norway between 1990 and 2007: A retrospective cohort study. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare. Volume 3, Issue 4, December 2012, Pages 147–153.

Nove, A., Berrington, A., & Matthews, Z. (2012). Comparing the odds of postpartum haemorrhage in planned home birth against planned hospital birth: results of an observational study of over 500,000 maternities in the UK. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 12(1), 130.

Lutomski, J., Byrne, B., Devane, D., & Greene, R. (2012). Increasing trends in atonic postpartum haemorrhage in Ireland: An 11-year population-based cohort study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 119(3), 306-314.

Callaghan, W. M., Kuklina, E. V., & Berg, C. J. (2010). Trends in postpartum hemorrhage: United States, 1994–2006. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 202(4), 353-e1.

Knight, M., Callaghan, W.M., Berg, C., Alexander, S., Bouvier-Colle, M.H., Ford, J.B., Joseph, K.S., Lewis, G., Liston, R.M., Roberts, C.L. & Oats, J. (2009). Trends in postpartum hemorrhage in high resource countries: a review and recommendations from the International Postpartum Hemorrhage Collaborative Group. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 9(1), 55.

Roberts, C. L., Ford, J. B., Algert, C. S., Bell, J. C., Simpson, J. M., & Morris, J. M. (2009). Trends in adverse maternal outcomes during childbirth: a population-based study of severe maternal morbidity. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 9(1), 7.

Nordström, L., Fogelstam, K., Fridman, G., Larsson, A., & Rydhstroem, H. (1997). Routine oxytocin in the third stage of labour: a placebo controlled randomised trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 104(7), 781-786.

Prichard, J. A., Baldwin, R. M., Dickey, J. C., & Wiggins, K. M. (1962). Blood volume changes in pregnancy and the puerperium. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 84, 1271-1282.

Prichard, J. A., Baldwin, R. M., Dickey, J. C., & Wiggins, K. M. (1962). Blood volume changes in pregnancy and the puerperium. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 84, 1271-1282.

Bloomfield, T. H., & Gordon, H. (1990). Reaction to blood loss at delivery. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 10(sup2), S13-S16.

Prasertcharoensuk, W., Swadpanich, U., & Lumbiganon, P. (2000). Accuracy of the blood loss estimation in the third stage of labor. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 71(1), 69-70.

Carroli, G., Cuesta, C., Abalos, E., & Gulmezoglu, A. M. (2008). Epidemiology of postpartum haemorrhage: a systematic review. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology, 22(6), 999-1012.

Selo-Ojeme, D. O. (2002). Primary postpartum haemorrhage. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 22(5), 463-469.

Prendiville, W. J., Harding, J. E., Elbourne, D. R., & Stirrat, G. M. (1988). The Bristol third stage trial: active versus physiological management of third stage of labour. Bmj, 297(6659), 1295-1300.

Salati, J. A., Leathersich, S. J., Williams, M. J., Cuthbert, A., & Tolosa, J. E. (2019). Prophylactic oxytocin for the third stage of labour to prevent postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (4).

Bateman, B. T., Berman, M. F., Riley, L. E., & Leffert, L. R. (2010). The epidemiology of postpartum hemorrhage in a large, nationwide sample of deliveries. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 110(5), 1368-1373.

World Health Organization. (2012). WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. World Health Organization.

Drugs.com. Retrieved from https://www.drugs.com/pro/pitocin.html April 10, 2020.

Prendiville, W. J., Elbourne, D., & McDonald, S. J. (2000). Active versus expectant management in the third stage of labour. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (3).

Sloan, N. L., Durocher, J., Aldrich, T., Blum, J., & Winikoff, B. (2010). What measured blood loss tells us about postpartum bleeding: a systematic review. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 117(7), 788-800.

Kroll‐Desrosiers, A. R., Nephew, B. C., Babb, J. A., Guilarte‐Walker, Y., Moore Simas, T. A., & Deligiannidis, K. M. (2017). Association of peripartum synthetic oxytocin administration and depressive and anxiety disorders within the first postpartum year. Depression and anxiety, 34(2), 137-146.

Gu, V., Feeley, N., Gold, I., Hayton, B., Robins, S., Mackinnon, A., Samuel, S., Carter, C.S. & Zelkowitz, P. (2016). Intrapartum synthetic oxytocin and its effects on maternal well‐being at 2 months postpartum. Birth, 43(1), 28-35.

Kramer, M. S., Dahhou, M., Vallerand, D., Liston, R., & Joseph, K. S. (2011). Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage: can we explain the recent temporal increase?. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 33(8), 810-819.

Wetta, L. A., Szychowski, J. M., Seals, S., Mancuso, M. S., Biggio, J. R., & Tita, A. T. (2013). Risk factors for uterine atony/postpartum hemorrhage requiring treatment after vaginal delivery. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 209(1), 51-e1.

Jangsten, E., Mattsson, L. Å., Lyckestam, I., Hellström, A. L., & Berg, M. (2011). A comparison of active management and expectant management of the third stage of labour: a Swedish randomised controlled trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 118(3), 362-369.

Mohamed, A., Bayoumy, H. A., Abou-Gamrah, A. A. S., & El-Shahawy, A. A. S. (2017). Placental cord drainage versus no placental drainage in the management of third stage of labour: Randomized controlled trial. The Egyptian Journal of Hospital Medicine, 68(1), 1042-1048.

Davis, D., Baddock, S., Pairman, S., Hunter, M., Benn, C., Anderson, J., Dixon, L. & Herbison, P. (2016). Risk of severe postpartum hemorrhage in low-risk childbearing women in new zealand: exploring the effect of place of birth and comparing third stage management of labor-Birth (Berkeley, Calif.)-Vol. 39, 2-ISBN: 1523-536X-p. 98-105.

Fahy, K., Hastie, C., Bisits, A., Marsh, C., Smith, L., & Saxton, A. (2010). Holistic physiological care compared with active management of the third stage of labour for women at low risk of postpartum haemorrhage: a cohort study. Women and Birth, 23(4), 146-152.

Mendelson, C. L. (1946). The aspiration of stomach contents into the lungs during obstetric anesthesia. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 1(6), 837-839.

Ludka, L. M., & Roberts, C. C. (1993). Eating and drinking in labor: a literature review. Journal of Nurse-Midwifery, 38(4), 199-207.

Rahmani, R., Khakbazan, Z., Yavari, P., Granmayeh, M., & Yavari, L. (2012). Effect of oral carbohydrate intake on labor progress: randomized controlled trial. Iranian journal of public health, 41(11), 59.

Khadem, N., Sharaphy, A., Latifnejad, R., Hammod, N., & Ibrahimzadeh, S. (2007). Comparing the efficacy of dates and oxytocin in the management of postpartum hemorrhage. Shiraz E-Medical Journal, 8(2), 64-71.

Saxton, A., Fahy, K., Rolfe, M., Skinner, V., & Hastie, C. (2015). Does skin-to-skin contact and breast feeding at birth affect the rate of primary postpartum haemorrhage: Results of a cohort study. Midwifery, 31(11), 1110-1117.

Ludington‐Hoe, S. M., Lewis, T., Morgan, K., Cong, X., Anderson, L., & Reese, S. (2006). Breast and infant temperatures with twins during shared kangaroo care. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 35(2), 223-231.

Perlman, J., & Kjaer, K. (2016). Neonatal and maternal temperature regulation during and after delivery. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 123(1), 168-172.

De Saintonge, D. C., Cross, K. W., Shathorn, M. K., Lewis, S. R., & Stothers, J. K. (1979). Hats for the newborn infant. Br Med J, 2(6190), 570-571.

Coles, E. C., & Valman, H. B. (1979). Hats for the newborn infant. British medical journal, 2(6192), 734.

Birth Hijacked – The Ritual Membrane Sweep

I’ve written about many topics over the years but nothing has ever generated as much discussion, opposition, and vitriol as challenging the cherished routine membrane sweep/stripping, aka stretch-and-sweep. A few years ago, I wrote a post about how I’d like to see the routine, prior-to-40-weeks, without-medical-indication membrane sweep banned from obstetrical and midwifery practice. I talked about its risks and the fact that the clients I worked with called it a sexual assault when done without consent

The post went viral and I received hate messages and emails from around the world defending this procedure. In general, the sentiment was that I should most definitely be having sexual relations with myself, after which, I should be locked up and forever silenced. I also heard from hundreds of women whose births were ruined by days of painful, non-progressing contractions triggered by a membrane sweep that ended up in a fully medicalised all-the-interventions arrival for their baby that they didn’t want. And horrifically, even more hundreds wrote to share their stories of non-consenting, painful, and violating membrane sweeping when there was no reason for it, aside from the care provider’s decision that they had agency over their patient’s vagina and could do what they wanted when they wanted.

So what is it about membrane sweeping that is so cherished that challenging it generates death threats?

Buckle up. Here we go again!

©Hanna-Barbera

I’ve written about many topics over the years but nothing has ever generated as much discussion, opposition, and vitriol as challenging the cherished routine membrane sweep/stripping, aka stretch-and-sweep.

A few years ago, I wrote a post about how I’d like to see the routine, prior-to-40-weeks, without-medical-indication membrane sweep banned from obstetrical and midwifery practice. I talked about its risks and the fact that the clients I worked with called it a sexual assault when done without consent

The post went viral and I received hate messages and emails from around the world defending this procedure. In general, the sentiment was that I should most definitely be having sexual relations with myself, after which, I should be locked up and forever silenced. I also heard from hundreds of women whose births were ruined by days of painful, non-progressing contractions triggered by a membrane sweep that ended up in a fully medicalised all-the-interventions arrival for their baby that they didn’t want. And horrifically, even more hundreds wrote to share their stories of non-consenting, painful, and violating membrane sweeping when there was no reason for it, aside from the care provider’s decision that they had agency over their patient’s vagina and could do what they wanted when they wanted.

That particular post was prompted by a brief encounter with a new mother. Her baby was little and we got talking. She told me how she went to her usual prenatal visit at 36 weeks and the doctor said it was time for a vaginal check to see how things were coming along. She thought that was an ok idea and stripped accordingly, lay down on the examining table and put her feet in the stirrups. However, rather than a simple vaginal exam, she experienced excruciating pain that had her crawling up the table trying to escape that probing hand. The doctor removed her bloodied glove and when this woman asked why she was bleeding, the doctor responded, “That should get things going”. This mother had experienced a non-consenting, unplanned, and unknowing stretch-and-sweep to start labour before she or the baby were ready. She went home bleeding and cramping and within a few days went into labour and birthed a baby that was not ready to breathe. The baby spent 3 days in the NICU and she was devastated. Her birth was hijacked by a damnable routine from someone who should have known better or at least given a damn.

Yes, that was obstetrical violence. However, the routine of membrane sweeping for the mere reason that the client is at term is a deeply embedded ritual in obstetrics and mimicked by some midwives. I don’t think there is one other procedure that so callously turns a normally progressing pregnancy into a pathological event than this heinous routine.

So what is it about membrane sweeping that is so cherished that challenging it generates death threats?

Routines are habits that help organise our days

Let’s begin with some clarity on what I’m challenging.

First and foremost, I am not challenging the right for a pregnant person to choose a membrane sweep as a means of expediting labour. I fully support an individual’s right and autonomy to choose what is best for them.

Secondly, I am not challenging this as a tool for expediting labour when there is a medical indication.

I am challenging the ROUTINE of membrane sweeping that is done by some care providers as part of their normal and usual prenatal “package”, without any hint that there is a reason to expedite the birth of the baby due to an emerging medical condition.

At your cervix, ma’am

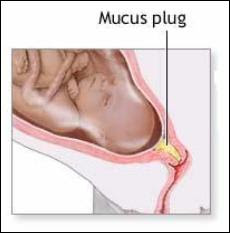

Let’s take a tour of the cervix. The cervix is a narrow passage that sits at the lower end of the uterus extending into the vagina. The cervix changes throughout the menstrual cycle and serves an important function in fertility. During ovulation, the cervix produces sperm-friendly mucus and becomes softer and more open to facilitate sperm reaching the ovum. When not ovulating, it produces sperm-unfriendly mucus and makes it more difficult for sperm to pass through to the uterus.

In pregnancy, the cervix fills with mucus, which creates a barrier to help prevent infection from passing through to the uterus. The cervix remains closed and rigid (like the tip of your nose) and is about 3-5 cm. long.

At term, in preparation for birth, the cervix will soften (like the inside of your cheek) due to the action of various hormones. The cervix is comprised of about 5-10% smooth muscle cells, which ensures it will stay closed and rigid throughout pregnancy. In preparation for labour, these muscle cells experience a programmed cellular death, which allows for the cervix to open (Leppert, 1995). The cervix will develop more oxytocin and prostaglandin receptors to help with the dilation process (Buckley, 2015). Prostaglandins, which are found abundantly in semen, ripens the cervix, digests the mucus plug, and promotes softening and shortening of the cervix.

Medical providers tend to give a great deal of attention to the cervix both prior to labour and in labour. It can provide some information that the medical folks find useful.

At term (around 40 weeks), the cervix can be felt to determine if it is ripening. Ripening means that the cervix is becoming softer, shorter, and is moving its position slightly forward. If so, it means that normal end-of-pregnancy hormones are doing their job. If not, it means that normal end-of-pregnancy hormones are doing their job, but they just haven’t gotten around to softening and shortening the cervix at the moment that a gloved hand is probing it.

This information is useful for planning an induction. A cervix that is shorter than 1.5 cm. is more predictive of spontaneous labour within the next 7-10 days than a longer cervix (Rao, Celik, Poggi, Poon, & Nicolaides, 2008). And a cervix that scores higher on the Bishop score is more predictive of an induction resulting in a vaginal birth rather than surgery (usually called “failure to progress”) (King, Pilliod, & Little, 2010). So that end-of pregnancy vaginal exam is about gathering information to plan your induction.

The other possibility for these routine (without medical indication) vaginal examinations in a healthy pregnancy is to develop submission and compliance in the client as she subjugates herself to the clinician by having her genitals penetrated by someone who is not her intimate partner.

Not too long ago, I was working with a postpartum client who was recovering from her birth experience. As a survivor of sexual assault she did not want anyone penetrating her genitals when she was labouring and giving birth and repeatedly told her midwife this. However, her midwife felt it was best for her to submit to vaginal exams in pregnancy to “get used to” them before she was in labour. Apparently, it never occurred to either of them that vaginal exams are optional and largely unnecessary for birthing a baby. In this case, the prenatal vaginal exams were for the purpose of building in submission and compliance so that the care providers could exercise agency over her body in labour.

Inductions: getting the baby out before it’s ready

An induction starts labour artificially before optimal hormonal physiology has prepared the baby and the mother for spontaneous birth. About 1 in 4 births begin by induction (BORN, 2013; Osterman & Martin, 2014). Although, there has been a slight decrease in inductions in recent years as fewer early-term inductions, meaning prior to 39 weeks, are performed. This has allowed more mothers to go into spontaneous labour without any additional adverse outcomes (Osterman & Martin, 2014). The cervix is one small part of the whole physiological process and since it can be reached easily by probing hands, it can provide a bit of information on whether an induction is likely to lead to a vaginal birth or is more likely to result in caesarean surgery.

There are lots of ways to artificially start labour before the mother or baby are ready. There are the so-called “natural” inductions:

Acupuncture and acupressure

Herbs and Homeopathy

Castor oil

Massage

Nipple stimulation

There are chemical inductions, which the literature calls “formal” inductions, as they require medical supervision:

Cervical ripening with prostaglandins

Intravenous synthetic oxytocin

And we have mechanical inductions, which also generally require medical supervision:

Artificial rupture of membranes aka “breaking the water”

Cervical ripening with a balloon catheter

Manual membrane sweeping/stripping, “stretch and sweep”

Ideally, an induction should only be suggested when the risks of staying pregnant outweigh the long and short-term risks of an induction. Depending on the method of induction those risks can include preterm birth, breathing problems in the baby, infection in the mother or baby, uterine hyper-stimulation, uterine rupture, fetal distress, breastfeeding failure, and rarely, death of either the mother or the baby.

Unfortunately, most inductions are done where the research affirms that the risks of an induction outweigh the risks of staying pregnant, including pre-labour rupture of membranes, gestational diabetes, suspected big baby, low fluid at term, isolated hypertension at term, twins, being “due”, or being “overdue” (Mozurkewich, Chilimigras, Koepke, Keeton, & King, 2009; Cohain, n.d.; Mandruzzato et al., 2010).

“membrane sweeping is a procedure meant to induce labour so that the client won’t be induced later”

Membrane sweeping: Fred Flintstone manipulating your physiology

Membrane sweeping involves the provider inserting their gloved hand into a mother’s vagina and manually stretching open the cervix and then running their finger around the opening of the cervix to separate the amniotic sack from the lower uterine segment. Caregivers will say it feels much like separating Velcro.

This procedure has the potential to trigger labour because it releases extra prostaglandins at the cervix. If the membrane sweep results in a shorter cervix, then it doesn’t make any difference in whether the mother is subsequently induced, but it does decrease the incidence of c-section. However, membrane sweeping is much more likely to result in cervical lengthening – which is predictive of NOT going into labour (Tan, Khine, Sabdin, Vallikkannu, & Sulaiman, 2011).

Prostaglandins are one of many important hormones that are needed for labour and birth. As pregnancy progresses and it’s getting time for the baby to be born, there are complex processes that prepare and protect the baby and are necessary for labour to commence. For example, the cervix and the uterus develop prostaglandin receptors so that necessary prostaglandins have a place to “land” or “connect” so that they can do their job. The uterus develops an abundance of oxytocin receptors so that this love hormone that is produced in the brain can connect with the uterus and cause contractions. The baby’s brain develops oxytocin receptors, which is neuro-protective for the journey ahead. There is an increase in estrogen, which activates the uterus for delivery. There are inflammatory processes within the uterus that help to mature the baby’s lungs to prepare for breathing on the outside. The baby’s brain develops increased epinephrine receptors to protect it from any gaps in oxygen during the birth. The mother’s brain develops endorphin receptors for natural pain relief. And there is an increase in prolactin to prepare the mother for breastfeeding and bonding. (Buckley, 2015)

When considering the finely-tuned and delicate interplay of complex and specific processes that brings the baby earth-side, a manual stretch-and-sweep at term without any medical indication is like getting Fred Flintstone to program an app that regulates the autonomic nervous system. It’s a crude, blunt instrument inserted into a complex system with the intention of bypassing evolutionarily necessary adaptive processes to cut the pregnancy short by a possible few days.

Let’s try to induce labour so we don’t have to induce labour

A Cochrane Review (Bouvain, Stan, & Irion, 2005) evaluated available studies comparing membrane sweeping to no sweeping. In general, this procedure can reduce the duration of pregnancy by up to three days. However, the authors noted that only small studies showed this reduction in pregnancy duration whereas larger studies didn’t, suggesting some bias. Because membrane sweeping doesn’t usually lead to immediate labour, it is not recommended when the need to get the baby out is urgent. Its primary use is to “prevent” a longer gestation and therefore an induction by more risky means.

A stretch-and-sweep is a procedure that is meant to induce labour so that you won’t be induced later. The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada wrote in their 2013 Practice Guideline, which was reaffirmed in 2015, that “routine sweeping (stripping) of membranes promotes the onset of labour and that this simple technique decreases induction rates.”

Again: membrane sweeping is a procedure meant to induce labour so that the client won’t be induced later.

It assumes that the later induction is non-negotiable and the client’s best hope is that this early induction “saves” her from the risks of the later induction.

This is no different than all those “natural” inductions that are employed when trying to induce labour so the mother doesn’t have experience an induction – or the challenge of just declining the planned induction. It takes the approach that planned inductions are non-negotiable. Of course, mothers may chose a natural induction as a means of expediting the births of their babies for a number of reasons and I fully support their autonomy and choice to do so.

If there is a medical need to get the baby out to preserve its or its mothers life, then this dyad should be under medical supervision and receiving the best medical care possible. We need to critically evaluate the mentality that says, “let’s try to induce so we don’t have to induce”.

We’ve bought into a culture where non-evidence-based time limits and spurious reasons are given for booking inductions that don’t line up with the science. Rather than supporting mothers in exploring the science, doing a targeted risk/benefit analysis based on her particular situation, and supporting the mother in informed decision making, we line up the early inductions hoping to out-smart, out-wit, and out-play the medical providers who routinely induce based on outdated information or habit or hospital protocols that are based in their insurance risk-management strategy.

If this procedure is not recommended when there is an urgent need to get the baby out (Bouvain et al., 2005) and its primary purpose is to prevent a later induction where the indication is a pregnancy continuing beyond the cut-off date of the caregiver or institution (SOGC, 2013), then it has no medical indication.

What else did the Cochrane Review find?

There was a high level of bias in many of the studies, in part, because there could be no blinding. The clinicians knew they were performing the procedure and the clients knew they’d received it due to discomfort and pain

It was an out-patient procedure meaning there was no urgent reason for the induction

It did not generally lead to labour within 24 hours

No difference in oxytocin augmentation, use of epidural, instrumental delivery, caesarean delivery, meconium staining, admission to the NICU, or Apgar score less than seven at five minutes between sweeping and non-sweeping. This means it didn’t show any benefit

No difference in pre-labour rupture of membranes, maternal infection or neonatal infection. However, it’s worth noting that the non-sweeping participants were subject to routine obstetrical services that includes many vaginal exams that increase pre-labour rupture of membranes and infection (Maharaj, 2007; Zanella et al., 2010; Lenihan, 1984; Critchfield et al., 2013)

Significant pain in the mother during the procedure

Vaginal bleeding after the procedure

Painful contractions for the next 24 hours not leading to labour

What we have here is a routine that hurts the mother and has no significant benefit – aside from maybe possibly putting her into labour before another planned induction.

As the Cochrane Review discovered, the likely outcome of a membrane sweep is painful non-progressing contractions. This is often mis-interpreted as “labour” and the client is sent to the hospital for an induction anyway because she’s been “in labour” for 24-48 hours without progress. This is the epitome of a hijacked birth that turns a normal physiological process into a pathological one leading to the cascade of interventions, sometimes all the way up to an unwanted and unplanned caesarean for “failure to progress”. To convert the natural process into a pathological one is part of the classic definition of obstetrical violence (D'Gregorio, 2010).

They call it ‘birth rape’

For those who experienced this without their prior knowledge or consent, their comments overwhelmingly spoke of rape. This was especially pronounced in those with a history of prior rape. Studies confirm that those with a history of rape experience the routines of industrial birth differently than those without a history of sexual assault. For survivors, procedures that are uneventful for others can inadvertently put them “back in the rape” (Halvorsen, Nerum, Øian, & Sørlie, 2013).

Frankly, it’s unconscionable that any care provider would brazenly take the opportunity to manually manipulate a woman’s cervix, knowing it introduces risks and has the potential to hurt her, without the express knowledge and consent of the client following an informed choice discussion.

While membrane sweeping is intended to induce labour, it’s also used on labouring women to hurry things along. During labour, the cervix is being moved and thinned by the action of uterine muscles contracting and pulling the cervix up and around the baby’s head. The cervix is working hard and it’s tender. Many women will report that they screamed, cried ‘no’, tried to kick the provider’s hand away, or tried to crawl up the bed to get away from the invasive exam.

I remember one dark cold February night, years ago, when I was called to be with a family in labour. There was an ice storm and my trip there was dangerous and precarious. Eventually, my car slid into their street and managed to stop somewhere close to the driveway. I quietly entered the house to hear a mother in the throes of glorious, deep, active labour. I knew it wouldn’t be long before the baby arrived. I announced myself and tiptoed upstairs to see her on hands and knees with more blood than I would have expected on the towel beneath her. She said she invited her midwife to the birth and expected her to be there any minute. Soon enough, a beautiful baby boy gently emerged and landed safely into his daddy’s waiting hands. By the time the midwives arrived, the new family was tucked into bed enjoying a post-birth snack and cup of tea.

As the new family was bonding, I joined the midwives downstairs who were making notes in their client’s medical charts to make them some tea and offer a snack. I overheard one midwife say, “Oh yeah, when I was here earlier, she was about 6cm so I did a stretch-and-sweep”.

“Oh yeah.

Now I remember.

She was in active labour so I did an invasive and painful procedure to speed things up during a dark and dangerous ice storm.

Without her knowing I would do that.”

This is nothing but reckless cruelty. Yet this kind of cruelty permeates maternity services where women are routinely hurt for the sole purpose of interfering in their physiology and the safety of the birth process in order to get the baby out before they do even more risky and dangerous things.

And that is why I would like to see the ROUTINE, WITHOUT MEDICAL INDICATION membrane sweep removed from obstetrical and midwifery practice. It shouldn’t be the luck of the draw that a pregnant client gets one of the “good ones” who only induces a client when there is a medical need, with an informed choice discussion, and full consent.

To return to my original question: what is it about membrane sweeping that is so cherished that challenging it generates death threats?

It’s a deeply embedded ritual in a toxic medical culture that presumes to take authority over a pregnant woman’s sexual organs for the purpose of dominating the physiological process and then becoming a hero to the interrupted physiology and complications that ensue. It’s about power and control. And challenging this is a dangerous act of sedition. Those who do this to their clients like being the hero and clients who defend this need to believe they were saved from something – otherwise the truth is just too awful.

Make wise choices.

Much love,

Mother Billie

#endobstetricalnonsense #informedconsent #obstetricalviolence #membranesweeping #stretchandsweep #withoutconsent #birthrape #failuretoprogress

References

Better Outcomes Registry Network. (BORN). 2013. Provincial Overview of Perinatal Health in 2011–2012.

Boulvain, M., Stan, C. M., & Irion, O. (2005). Membrane sweeping for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1).

Buckley, S. J. (2015). Hormonal physiology of childbearing: Evidence and implications for women, babies, and maternity care. Washington, DC: Childbirth Connection Programs, National Partnership for Women & Families.

Cohain, J. S. Reducing Inductions: Lack of Justification to Induce for “Postdates”.

Critchfield, A. S., Yao, G., Jaishankar, A., Friedlander, R. S., Lieleg, O., Doyle, P. S., ... & Ribbeck, K. (2013). Cervical mucus properties stratify risk for preterm birth. PloS one, 8(8), e69528.

D'Gregorio, R. P. (2010). Obstetric violence: a new legal term introduced in Venezuela.

Halvorsen, L., Nerum, H., Øian, P., & Sørlie, T. (2013). Giving birth with rape in one's past: a qualitative study. Birth, 40(3), 182-191.

King, V., Pilliod, R., & Little, A. (2010). Rapid review: Elective induction of labor. Portland: Center for Evidence-based Policy.

Lenihan, J. J. (1984). Relationship of antepartum pelvic examinations to premature rupture of the membranes. Obstetrics and gynecology, 63(1), 33-37.

Leppert, P. C. (1995). Anatomy and physiology of cervical ripening. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology, 38(2), 267-279.

Maharaj, D. (2007). Puerperal pyrexia: a review. Part II. Obstetrical & gynecological survey, 62(6), 400-406.

Mandruzzato, G., Alfirevic, Z., Chervenak, F., Gruenebaum, A., Heimstad, R., Heinonen, S., ... & Thilaganathan, B. (2010). Guidelines for the management of postterm pregnancy. Journal of perinatal medicine, 38(2), 111-119.

Mozurkewich, E., Chilimigras, J., Koepke, E., Keeton, K., & King, V. J. (2009). Indications for induction of labour: a best‐evidence review. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 116(5), 626-636.

Osterman, M. J., & Martin, J. A. (2014). Recent declines in induction of labor by gestational age.

Rao, A., Celik, E., Poggi, S., Poon, L., & Nicolaides, K. H. (2008). Cervical length and maternal factors in expectantly managed prolonged pregnancy: prediction of onset of labor and mode of delivery. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology: The Official Journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 32(5), 646-65.

Rayburn, W. F., & Zhang, J. (2002). Rising rates of labor induction: present concerns and future strategies. Obstetrics & gynecology, 100(1), 164-167.

Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. SOGC. 2013. Clinical Practice Guideline, No. 296, Indution of Labour.

Tan, P. C., Khine, P. P., Sabdin, N. H., Vallikkannu, N., & Sulaiman, S. (2011). Effect of membrane sweeping on cervical length by transvaginal ultrasonography and impact of cervical shortening on cesarean delivery. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, 30(2), 227-233.

Zanella, P., Bogana, G., Ciullo, R., Zambon, A., Serena, A., & Albertin, M. A. (2010). Chorioamnionitis in the delivery room. Minerva pediatrica, 62(3 Suppl 1), 151-153.

When not to induce – reason #408 – a placenta with calcium deposits

I received yet another phone call from someone who was trying to sort out the risks of staying pregnant versus the risks of being induced. From what the client could share, it was hard to know if the practitioner wasn’t fully informed on placental calcification at term, or wasn’t fully forthcoming about the non-clinical indications of that particular development in a healthy pregnancy.

To be sure, there are times when the benefits of an induction to rescue a compromised baby far outweigh the short and long-term risks of an induction.

Unfortunately, when trying to make an informed decision, clients often need to learn what their practitioners don’t know or won’t tell them.

“I’m 3 days overdue and my midwife says I need to be induced because my placenta is calcifying and that means it’s dying.”

I received yet another phone call from someone who was trying to sort out the risks of staying pregnant versus the risks of being induced. From what the client could share, it was hard to know if the practitioner wasn’t fully informed on placental calcification at term, or wasn’t fully forthcoming about the non-clinical indications of that particular development in a healthy pregnancy.

To be sure, there are times when the benefits of an induction to rescue a compromised baby far outweigh the short and long-term risks of an induction.

Unfortunately, when trying to make an informed decision, clients often need to learn what their practitioners don’t know or won’t tell them. So let’s take a little tour of the placenta.

© Billie Harrigan Consulting