Birth Hijacked – The Ritual Membrane Sweep

I’ve written about many topics over the years but nothing has ever generated as much discussion, opposition, and vitriol as challenging the cherished routine membrane sweep/stripping, aka stretch-and-sweep. A few years ago, I wrote a post about how I’d like to see the routine, prior-to-40-weeks, without-medical-indication membrane sweep banned from obstetrical and midwifery practice. I talked about its risks and the fact that the clients I worked with called it a sexual assault when done without consent

The post went viral and I received hate messages and emails from around the world defending this procedure. In general, the sentiment was that I should most definitely be having sexual relations with myself, after which, I should be locked up and forever silenced. I also heard from hundreds of women whose births were ruined by days of painful, non-progressing contractions triggered by a membrane sweep that ended up in a fully medicalised all-the-interventions arrival for their baby that they didn’t want. And horrifically, even more hundreds wrote to share their stories of non-consenting, painful, and violating membrane sweeping when there was no reason for it, aside from the care provider’s decision that they had agency over their patient’s vagina and could do what they wanted when they wanted.

So what is it about membrane sweeping that is so cherished that challenging it generates death threats?

Buckle up. Here we go again!

©Hanna-Barbera

I’ve written about many topics over the years but nothing has ever generated as much discussion, opposition, and vitriol as challenging the cherished routine membrane sweep/stripping, aka stretch-and-sweep.

A few years ago, I wrote a post about how I’d like to see the routine, prior-to-40-weeks, without-medical-indication membrane sweep banned from obstetrical and midwifery practice. I talked about its risks and the fact that the clients I worked with called it a sexual assault when done without consent

The post went viral and I received hate messages and emails from around the world defending this procedure. In general, the sentiment was that I should most definitely be having sexual relations with myself, after which, I should be locked up and forever silenced. I also heard from hundreds of women whose births were ruined by days of painful, non-progressing contractions triggered by a membrane sweep that ended up in a fully medicalised all-the-interventions arrival for their baby that they didn’t want. And horrifically, even more hundreds wrote to share their stories of non-consenting, painful, and violating membrane sweeping when there was no reason for it, aside from the care provider’s decision that they had agency over their patient’s vagina and could do what they wanted when they wanted.

That particular post was prompted by a brief encounter with a new mother. Her baby was little and we got talking. She told me how she went to her usual prenatal visit at 36 weeks and the doctor said it was time for a vaginal check to see how things were coming along. She thought that was an ok idea and stripped accordingly, lay down on the examining table and put her feet in the stirrups. However, rather than a simple vaginal exam, she experienced excruciating pain that had her crawling up the table trying to escape that probing hand. The doctor removed her bloodied glove and when this woman asked why she was bleeding, the doctor responded, “That should get things going”. This mother had experienced a non-consenting, unplanned, and unknowing stretch-and-sweep to start labour before she or the baby were ready. She went home bleeding and cramping and within a few days went into labour and birthed a baby that was not ready to breathe. The baby spent 3 days in the NICU and she was devastated. Her birth was hijacked by a damnable routine from someone who should have known better or at least given a damn.

Yes, that was obstetrical violence. However, the routine of membrane sweeping for the mere reason that the client is at term is a deeply embedded ritual in obstetrics and mimicked by some midwives. I don’t think there is one other procedure that so callously turns a normally progressing pregnancy into a pathological event than this heinous routine.

So what is it about membrane sweeping that is so cherished that challenging it generates death threats?

Routines are habits that help organise our days

Let’s begin with some clarity on what I’m challenging.

First and foremost, I am not challenging the right for a pregnant person to choose a membrane sweep as a means of expediting labour. I fully support an individual’s right and autonomy to choose what is best for them.

Secondly, I am not challenging this as a tool for expediting labour when there is a medical indication.

I am challenging the ROUTINE of membrane sweeping that is done by some care providers as part of their normal and usual prenatal “package”, without any hint that there is a reason to expedite the birth of the baby due to an emerging medical condition.

At your cervix, ma’am

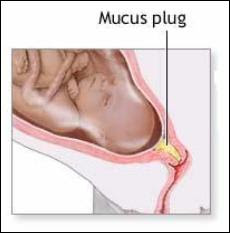

Let’s take a tour of the cervix. The cervix is a narrow passage that sits at the lower end of the uterus extending into the vagina. The cervix changes throughout the menstrual cycle and serves an important function in fertility. During ovulation, the cervix produces sperm-friendly mucus and becomes softer and more open to facilitate sperm reaching the ovum. When not ovulating, it produces sperm-unfriendly mucus and makes it more difficult for sperm to pass through to the uterus.

In pregnancy, the cervix fills with mucus, which creates a barrier to help prevent infection from passing through to the uterus. The cervix remains closed and rigid (like the tip of your nose) and is about 3-5 cm. long.

At term, in preparation for birth, the cervix will soften (like the inside of your cheek) due to the action of various hormones. The cervix is comprised of about 5-10% smooth muscle cells, which ensures it will stay closed and rigid throughout pregnancy. In preparation for labour, these muscle cells experience a programmed cellular death, which allows for the cervix to open (Leppert, 1995). The cervix will develop more oxytocin and prostaglandin receptors to help with the dilation process (Buckley, 2015). Prostaglandins, which are found abundantly in semen, ripens the cervix, digests the mucus plug, and promotes softening and shortening of the cervix.

Medical providers tend to give a great deal of attention to the cervix both prior to labour and in labour. It can provide some information that the medical folks find useful.

At term (around 40 weeks), the cervix can be felt to determine if it is ripening. Ripening means that the cervix is becoming softer, shorter, and is moving its position slightly forward. If so, it means that normal end-of-pregnancy hormones are doing their job. If not, it means that normal end-of-pregnancy hormones are doing their job, but they just haven’t gotten around to softening and shortening the cervix at the moment that a gloved hand is probing it.

This information is useful for planning an induction. A cervix that is shorter than 1.5 cm. is more predictive of spontaneous labour within the next 7-10 days than a longer cervix (Rao, Celik, Poggi, Poon, & Nicolaides, 2008). And a cervix that scores higher on the Bishop score is more predictive of an induction resulting in a vaginal birth rather than surgery (usually called “failure to progress”) (King, Pilliod, & Little, 2010). So that end-of pregnancy vaginal exam is about gathering information to plan your induction.

The other possibility for these routine (without medical indication) vaginal examinations in a healthy pregnancy is to develop submission and compliance in the client as she subjugates herself to the clinician by having her genitals penetrated by someone who is not her intimate partner.

Not too long ago, I was working with a postpartum client who was recovering from her birth experience. As a survivor of sexual assault she did not want anyone penetrating her genitals when she was labouring and giving birth and repeatedly told her midwife this. However, her midwife felt it was best for her to submit to vaginal exams in pregnancy to “get used to” them before she was in labour. Apparently, it never occurred to either of them that vaginal exams are optional and largely unnecessary for birthing a baby. In this case, the prenatal vaginal exams were for the purpose of building in submission and compliance so that the care providers could exercise agency over her body in labour.

Inductions: getting the baby out before it’s ready

An induction starts labour artificially before optimal hormonal physiology has prepared the baby and the mother for spontaneous birth. About 1 in 4 births begin by induction (BORN, 2013; Osterman & Martin, 2014). Although, there has been a slight decrease in inductions in recent years as fewer early-term inductions, meaning prior to 39 weeks, are performed. This has allowed more mothers to go into spontaneous labour without any additional adverse outcomes (Osterman & Martin, 2014). The cervix is one small part of the whole physiological process and since it can be reached easily by probing hands, it can provide a bit of information on whether an induction is likely to lead to a vaginal birth or is more likely to result in caesarean surgery.

There are lots of ways to artificially start labour before the mother or baby are ready. There are the so-called “natural” inductions:

Acupuncture and acupressure

Herbs and Homeopathy

Castor oil

Massage

Nipple stimulation

There are chemical inductions, which the literature calls “formal” inductions, as they require medical supervision:

Cervical ripening with prostaglandins

Intravenous synthetic oxytocin

And we have mechanical inductions, which also generally require medical supervision:

Artificial rupture of membranes aka “breaking the water”

Cervical ripening with a balloon catheter

Manual membrane sweeping/stripping, “stretch and sweep”

Ideally, an induction should only be suggested when the risks of staying pregnant outweigh the long and short-term risks of an induction. Depending on the method of induction those risks can include preterm birth, breathing problems in the baby, infection in the mother or baby, uterine hyper-stimulation, uterine rupture, fetal distress, breastfeeding failure, and rarely, death of either the mother or the baby.

Unfortunately, most inductions are done where the research affirms that the risks of an induction outweigh the risks of staying pregnant, including pre-labour rupture of membranes, gestational diabetes, suspected big baby, low fluid at term, isolated hypertension at term, twins, being “due”, or being “overdue” (Mozurkewich, Chilimigras, Koepke, Keeton, & King, 2009; Cohain, n.d.; Mandruzzato et al., 2010).

“membrane sweeping is a procedure meant to induce labour so that the client won’t be induced later”

Membrane sweeping: Fred Flintstone manipulating your physiology

Membrane sweeping involves the provider inserting their gloved hand into a mother’s vagina and manually stretching open the cervix and then running their finger around the opening of the cervix to separate the amniotic sack from the lower uterine segment. Caregivers will say it feels much like separating Velcro.

This procedure has the potential to trigger labour because it releases extra prostaglandins at the cervix. If the membrane sweep results in a shorter cervix, then it doesn’t make any difference in whether the mother is subsequently induced, but it does decrease the incidence of c-section. However, membrane sweeping is much more likely to result in cervical lengthening – which is predictive of NOT going into labour (Tan, Khine, Sabdin, Vallikkannu, & Sulaiman, 2011).

Prostaglandins are one of many important hormones that are needed for labour and birth. As pregnancy progresses and it’s getting time for the baby to be born, there are complex processes that prepare and protect the baby and are necessary for labour to commence. For example, the cervix and the uterus develop prostaglandin receptors so that necessary prostaglandins have a place to “land” or “connect” so that they can do their job. The uterus develops an abundance of oxytocin receptors so that this love hormone that is produced in the brain can connect with the uterus and cause contractions. The baby’s brain develops oxytocin receptors, which is neuro-protective for the journey ahead. There is an increase in estrogen, which activates the uterus for delivery. There are inflammatory processes within the uterus that help to mature the baby’s lungs to prepare for breathing on the outside. The baby’s brain develops increased epinephrine receptors to protect it from any gaps in oxygen during the birth. The mother’s brain develops endorphin receptors for natural pain relief. And there is an increase in prolactin to prepare the mother for breastfeeding and bonding. (Buckley, 2015)

When considering the finely-tuned and delicate interplay of complex and specific processes that brings the baby earth-side, a manual stretch-and-sweep at term without any medical indication is like getting Fred Flintstone to program an app that regulates the autonomic nervous system. It’s a crude, blunt instrument inserted into a complex system with the intention of bypassing evolutionarily necessary adaptive processes to cut the pregnancy short by a possible few days.

Let’s try to induce labour so we don’t have to induce labour

A Cochrane Review (Bouvain, Stan, & Irion, 2005) evaluated available studies comparing membrane sweeping to no sweeping. In general, this procedure can reduce the duration of pregnancy by up to three days. However, the authors noted that only small studies showed this reduction in pregnancy duration whereas larger studies didn’t, suggesting some bias. Because membrane sweeping doesn’t usually lead to immediate labour, it is not recommended when the need to get the baby out is urgent. Its primary use is to “prevent” a longer gestation and therefore an induction by more risky means.

A stretch-and-sweep is a procedure that is meant to induce labour so that you won’t be induced later. The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada wrote in their 2013 Practice Guideline, which was reaffirmed in 2015, that “routine sweeping (stripping) of membranes promotes the onset of labour and that this simple technique decreases induction rates.”

Again: membrane sweeping is a procedure meant to induce labour so that the client won’t be induced later.

It assumes that the later induction is non-negotiable and the client’s best hope is that this early induction “saves” her from the risks of the later induction.

This is no different than all those “natural” inductions that are employed when trying to induce labour so the mother doesn’t have experience an induction – or the challenge of just declining the planned induction. It takes the approach that planned inductions are non-negotiable. Of course, mothers may chose a natural induction as a means of expediting the births of their babies for a number of reasons and I fully support their autonomy and choice to do so.

If there is a medical need to get the baby out to preserve its or its mothers life, then this dyad should be under medical supervision and receiving the best medical care possible. We need to critically evaluate the mentality that says, “let’s try to induce so we don’t have to induce”.

We’ve bought into a culture where non-evidence-based time limits and spurious reasons are given for booking inductions that don’t line up with the science. Rather than supporting mothers in exploring the science, doing a targeted risk/benefit analysis based on her particular situation, and supporting the mother in informed decision making, we line up the early inductions hoping to out-smart, out-wit, and out-play the medical providers who routinely induce based on outdated information or habit or hospital protocols that are based in their insurance risk-management strategy.

If this procedure is not recommended when there is an urgent need to get the baby out (Bouvain et al., 2005) and its primary purpose is to prevent a later induction where the indication is a pregnancy continuing beyond the cut-off date of the caregiver or institution (SOGC, 2013), then it has no medical indication.

What else did the Cochrane Review find?

There was a high level of bias in many of the studies, in part, because there could be no blinding. The clinicians knew they were performing the procedure and the clients knew they’d received it due to discomfort and pain

It was an out-patient procedure meaning there was no urgent reason for the induction

It did not generally lead to labour within 24 hours

No difference in oxytocin augmentation, use of epidural, instrumental delivery, caesarean delivery, meconium staining, admission to the NICU, or Apgar score less than seven at five minutes between sweeping and non-sweeping. This means it didn’t show any benefit

No difference in pre-labour rupture of membranes, maternal infection or neonatal infection. However, it’s worth noting that the non-sweeping participants were subject to routine obstetrical services that includes many vaginal exams that increase pre-labour rupture of membranes and infection (Maharaj, 2007; Zanella et al., 2010; Lenihan, 1984; Critchfield et al., 2013)

Significant pain in the mother during the procedure

Vaginal bleeding after the procedure

Painful contractions for the next 24 hours not leading to labour

What we have here is a routine that hurts the mother and has no significant benefit – aside from maybe possibly putting her into labour before another planned induction.

As the Cochrane Review discovered, the likely outcome of a membrane sweep is painful non-progressing contractions. This is often mis-interpreted as “labour” and the client is sent to the hospital for an induction anyway because she’s been “in labour” for 24-48 hours without progress. This is the epitome of a hijacked birth that turns a normal physiological process into a pathological one leading to the cascade of interventions, sometimes all the way up to an unwanted and unplanned caesarean for “failure to progress”. To convert the natural process into a pathological one is part of the classic definition of obstetrical violence (D'Gregorio, 2010).

They call it ‘birth rape’

For those who experienced this without their prior knowledge or consent, their comments overwhelmingly spoke of rape. This was especially pronounced in those with a history of prior rape. Studies confirm that those with a history of rape experience the routines of industrial birth differently than those without a history of sexual assault. For survivors, procedures that are uneventful for others can inadvertently put them “back in the rape” (Halvorsen, Nerum, Øian, & Sørlie, 2013).

Frankly, it’s unconscionable that any care provider would brazenly take the opportunity to manually manipulate a woman’s cervix, knowing it introduces risks and has the potential to hurt her, without the express knowledge and consent of the client following an informed choice discussion.

While membrane sweeping is intended to induce labour, it’s also used on labouring women to hurry things along. During labour, the cervix is being moved and thinned by the action of uterine muscles contracting and pulling the cervix up and around the baby’s head. The cervix is working hard and it’s tender. Many women will report that they screamed, cried ‘no’, tried to kick the provider’s hand away, or tried to crawl up the bed to get away from the invasive exam.

I remember one dark cold February night, years ago, when I was called to be with a family in labour. There was an ice storm and my trip there was dangerous and precarious. Eventually, my car slid into their street and managed to stop somewhere close to the driveway. I quietly entered the house to hear a mother in the throes of glorious, deep, active labour. I knew it wouldn’t be long before the baby arrived. I announced myself and tiptoed upstairs to see her on hands and knees with more blood than I would have expected on the towel beneath her. She said she invited her midwife to the birth and expected her to be there any minute. Soon enough, a beautiful baby boy gently emerged and landed safely into his daddy’s waiting hands. By the time the midwives arrived, the new family was tucked into bed enjoying a post-birth snack and cup of tea.

As the new family was bonding, I joined the midwives downstairs who were making notes in their client’s medical charts to make them some tea and offer a snack. I overheard one midwife say, “Oh yeah, when I was here earlier, she was about 6cm so I did a stretch-and-sweep”.

“Oh yeah.

Now I remember.

She was in active labour so I did an invasive and painful procedure to speed things up during a dark and dangerous ice storm.

Without her knowing I would do that.”

This is nothing but reckless cruelty. Yet this kind of cruelty permeates maternity services where women are routinely hurt for the sole purpose of interfering in their physiology and the safety of the birth process in order to get the baby out before they do even more risky and dangerous things.

And that is why I would like to see the ROUTINE, WITHOUT MEDICAL INDICATION membrane sweep removed from obstetrical and midwifery practice. It shouldn’t be the luck of the draw that a pregnant client gets one of the “good ones” who only induces a client when there is a medical need, with an informed choice discussion, and full consent.

To return to my original question: what is it about membrane sweeping that is so cherished that challenging it generates death threats?

It’s a deeply embedded ritual in a toxic medical culture that presumes to take authority over a pregnant woman’s sexual organs for the purpose of dominating the physiological process and then becoming a hero to the interrupted physiology and complications that ensue. It’s about power and control. And challenging this is a dangerous act of sedition. Those who do this to their clients like being the hero and clients who defend this need to believe they were saved from something – otherwise the truth is just too awful.

Make wise choices.

Much love,

Mother Billie

#endobstetricalnonsense #informedconsent #obstetricalviolence #membranesweeping #stretchandsweep #withoutconsent #birthrape #failuretoprogress

References

Better Outcomes Registry Network. (BORN). 2013. Provincial Overview of Perinatal Health in 2011–2012.

Boulvain, M., Stan, C. M., & Irion, O. (2005). Membrane sweeping for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1).

Buckley, S. J. (2015). Hormonal physiology of childbearing: Evidence and implications for women, babies, and maternity care. Washington, DC: Childbirth Connection Programs, National Partnership for Women & Families.

Cohain, J. S. Reducing Inductions: Lack of Justification to Induce for “Postdates”.

Critchfield, A. S., Yao, G., Jaishankar, A., Friedlander, R. S., Lieleg, O., Doyle, P. S., ... & Ribbeck, K. (2013). Cervical mucus properties stratify risk for preterm birth. PloS one, 8(8), e69528.

D'Gregorio, R. P. (2010). Obstetric violence: a new legal term introduced in Venezuela.

Halvorsen, L., Nerum, H., Øian, P., & Sørlie, T. (2013). Giving birth with rape in one's past: a qualitative study. Birth, 40(3), 182-191.

King, V., Pilliod, R., & Little, A. (2010). Rapid review: Elective induction of labor. Portland: Center for Evidence-based Policy.

Lenihan, J. J. (1984). Relationship of antepartum pelvic examinations to premature rupture of the membranes. Obstetrics and gynecology, 63(1), 33-37.

Leppert, P. C. (1995). Anatomy and physiology of cervical ripening. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology, 38(2), 267-279.

Maharaj, D. (2007). Puerperal pyrexia: a review. Part II. Obstetrical & gynecological survey, 62(6), 400-406.

Mandruzzato, G., Alfirevic, Z., Chervenak, F., Gruenebaum, A., Heimstad, R., Heinonen, S., ... & Thilaganathan, B. (2010). Guidelines for the management of postterm pregnancy. Journal of perinatal medicine, 38(2), 111-119.

Mozurkewich, E., Chilimigras, J., Koepke, E., Keeton, K., & King, V. J. (2009). Indications for induction of labour: a best‐evidence review. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 116(5), 626-636.

Osterman, M. J., & Martin, J. A. (2014). Recent declines in induction of labor by gestational age.

Rao, A., Celik, E., Poggi, S., Poon, L., & Nicolaides, K. H. (2008). Cervical length and maternal factors in expectantly managed prolonged pregnancy: prediction of onset of labor and mode of delivery. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology: The Official Journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 32(5), 646-65.

Rayburn, W. F., & Zhang, J. (2002). Rising rates of labor induction: present concerns and future strategies. Obstetrics & gynecology, 100(1), 164-167.

Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. SOGC. 2013. Clinical Practice Guideline, No. 296, Indution of Labour.

Tan, P. C., Khine, P. P., Sabdin, N. H., Vallikkannu, N., & Sulaiman, S. (2011). Effect of membrane sweeping on cervical length by transvaginal ultrasonography and impact of cervical shortening on cesarean delivery. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, 30(2), 227-233.

Zanella, P., Bogana, G., Ciullo, R., Zambon, A., Serena, A., & Albertin, M. A. (2010). Chorioamnionitis in the delivery room. Minerva pediatrica, 62(3 Suppl 1), 151-153.

Birthing after Trauma – Seeing the Bigger Picture

It’s frustrating for care providers when their client comes armed with a 10-page birth plan, an army of doulas, and a mistrustful and hostile attitude. Care providers exist for the sole purpose of providing medical or midwifery services for pregnant, birthing, and postpartum clients and their goal is to help them emerge healthy and whole. Unfortunately, this creates friction before the relationship begins.

A mistrustful client has probably already had her trust broken by someone else long before they come armed with the minute details of how they need things to unfold. They may have already experienced abuse, neglect, sexual assault, victimisation, and trauma. Their trauma might have been the result of an abusive childhood, racial adversity, marginalisation, being the victim of a crime, or it might have been the result of a previous traumatic birth experience.

Published on Birth Trauma Ontario November 11, 2018

It Begins with a Mistrustful Client

Photo Martin Walls freeimages.com

It’s frustrating for care providers when their client comes armed with a 10-page birth plan, an army of doulas, and a mistrustful and hostile attitude. Care providers exist for the sole purpose of providing medical or midwifery services for pregnant, birthing, and postpartum clients and their goal is to help them emerge healthy and whole. Unfortunately, this creates friction before the relationship begins.

A mistrustful client has probably already had her trust broken by someone else long before they come armed with the minute details of how they need things to unfold. They may have already experienced abuse, neglect, sexual assault, victimisation, and trauma. Their trauma might have been the result of an abusive childhood, racial adversity, marginalisation, being the victim of a crime, or it might have been the result of a previous traumatic birth experience.

Birth Trauma Changes the Individual

Birth trauma doesn’t just happen. It’s not connected to an emergency or an unexpected outcome. These parents are not looking for someone to blame. Birth trauma is the result of clearly defined factors where the greatest indicator is a breakdown in the relationship between the care providers and the client (Harris & Ayers, 2012). The birthing mother felt disrespected, lied to, coerced, bullied, ignored, unsupported, and like she was just another cog in the wheel (Beck 2004; Reed, Reed, Sharman & Inglis, 2017). When this is partnered with pre-existing risk factors, this individual is at risk for developing postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder (Wu, Molteni, Ying, & Gomez-Pinilla, 2003; Faravelli, Giugni, Salvatori, & Ricca, 2004; Fromm, Heath, Vink, & Nimmo, 2004; Cortina &Kubiak, 2006; Eby & Eby, 2006; Sarandol et al., 2007; Lev-Wiesel, Chen, Daphna-Tekoah, & Hod, 2009; Roberts, Austin, Corliss, Vandermorris, & Koenen, 2010; Beck, Gable, Sakala, & Declercq, 2011; Cisternas et al., 2015; Matsumura et al., 2016; Du et al., 2016).

When parents have had a traumatic birth (about one third of all parents), they are much less likely to have another child, even if they wanted a larger family. In fact, they are twice as likely to not have another baby as someone who had a positive experience. If they choose to have another baby, the spacing between babies is twice as long as someone who had a positive experience. It takes them a much longer time to work up to doing it again (Gottvall & Waldenström, 2002).

Birthing after a traumatic experience is very different than preparing to birth a first child or another baby after a positive experience. These mothers are likely still dealing with the symptoms of trauma – flashbacks, sleep disturbances, terror, rage, difficulty forming new memories, hyperarousal always being on guard, and avoidance of triggers – including care providers and hospitals. These mothers are also more likely to be dealing with depression, anxiety, changes in their functional capacity, and suicidal thoughts than mothers without trauma. (DSM-5, 2013; Brady, Killeen, Brewerton, & Lucerini, 2000; Cook et al., 2004; Tavares et al., 2012).

When a Parent-of-Trauma Gets Pregnant Again

When a woman has had a traumatic birth and may still be suffering the effects of trauma, a new pregnancy can be a profoundly challenging time for her. She must now come face-to-face with the possibility that she will possibly endure the same horror in order to welcome this child into the world. Feelings of desperation, despair, fear, terror, and suicidal thoughts are not uncommon. Thoughts of running away and birthing alone in the woods are also common. This dread often interferes with bonding to her baby. (Beck & Watson, 2010)

The healthcare and birthing choices these parents make for subsequent births can be quite varied and diverse. Some might choose the same provider and location simply because it’s familiar and they know what’s coming. They know that they survived it the first time, and therefore can survive it again.

They might plan a caesarean section to gain the most control over the event. This way they can choose the surgeon, the day, and their support team. They won’t be facing the unknowns of whichever provider is on call.

If a mother chooses a vaginal birth, its very common for them to hire a doula as an advocate, to change providers, hospitals, plan a homebirth, or even birth in another city.

Unassisted Birth Choices

Freebirth, unassisted birth, or family birth, where there is no licensed medical attendant present, is a choice that is appearing more frequently in many developed countries (Holton & de Miranda, 2016). It’s a choice that is more common among parents who are birthing after trauma. Unassisted birth choices speak to the resistance that can be a response to the biomedical model of birth. Some families are finding that the obstetrical and midwifery model of risk-aversion and risk management removes their autonomy, and violates their culture, values, faith, or at times, their sexuality. If a mother has received disrespectful care, then they are more likely to avoid these services for subsequent pregnancies (UNPA, 2004). In an online survey of families that chose an unassisted birth, over half identified a previous negative hospital experience as the reason for their choice (O’Day, 2016). While there is no licensed medical attendant present, an unassisted birth may include the support of family members, doulas, traditional birth attendants, or other companions.

No matter what the mother-of-trauma chooses, she is disadvantaged because she can’t control for the behaviour of others in the medical system that don’t understand or respect her trauma or her perspective. Even the mother who chooses an unassisted birth may still be persecuted by hostile services if she transfers to the hospital for medical care (Vedam et al., 2017). Many a mother seeking medical support is “welcomed” by a harassing call to child protective services to investigate whether she is “conforming” to conventional medical services (Diaz-Tello, 2016). Online forums are filled with discussions on how to manage a possible trip to the hospital or doctor and how to prepare for a potentially harassing call to Childrens Aid Society (CAS), including sharing contact information for advocates and legal services. Indeed, misinformed providers are participating in this spiraling disconnect between clients and needed healthcare services.

Inappropriate Responses to Unconventional Choices

Providers will note that some of their clients decline the usual suite of obstetrical or midwifery services. For some clients, it’s an evidence-based decision. And for others, they are trying to avoid triggering their symptoms of trauma (Beck & Watson, 2010). Again, ill-equipped providers have been known to report these mothers to CAS, thinking that their health care choices are dangerous to the fetus. These are potentially well-meaning individuals, but have violated their professional ethics, as they cannot induce duress, bullying, or coercion to gain compliance (Health Care Consent Act, 1996). Further, the fetus has no citizenship and investigation by CAS regarding a fetus would be tantamount to harassment. However, this is one more obstacle that mothers-of-trauma often must navigate as they disentangle themselves from disrespectful care.

The consequence of these inappropriate actions from care providers is that mothers-of trauma will often decline further medical services for their babies once they are born, or to seek follow-up care or breastfeeding support (Finlayson & Downe, 2013; Moyer, Adongo, Aborigo, Hodgson, & Engmann, 2014). While pregnant, they may lie about their plans, their health, and other pertinent information, thereby missing an opportunity to form a collaborative relationship that could build lifetime wellness and resilience. They may choose to birth their babies without assistance and then tell their care provider that it just happened “too quickly”. This is ongoing evidence of the breakdown in the relationship between client and clinician.

Where Doulas Can Help

Doulas are the client’s and the clinician’s greatest ally as they generally develop the trust of the pregnant family and offer to serve as their advocate. Doulas can have a significant impact on the client’s outcome by reducing the need for surgery, assisted delivery, analgesia, and contributing to the reduction in low Apgars for the baby, and postpartum depression for the mother (Bohren, Hofmeyr, Sakala, Fukuzawa, & Cuthbert, 2017). Without the risk of reporting a non-compliant client, it is the doula that is privy to the client’s previous traumatic experience, the client’s coping strategies, and the wellbeing of the family. The doula has the opportunity to connect the client to resources in their community or to serve as a companion at medical visits. The rise of the doula to support families is indicative of a system that routinely denies birthing individuals informed choice, dignified care, and trauma-informed care (Dahlen, Jackson, & Stevens, 2011). Unfortunately, the burnout rate for doulas is very high due to vicarious trauma and institutional hostility (Naiman-Sessions, Henley, & Roth, 2017), meaning that experienced doulas are hard to find and it’s nearly impossible to foster their growth within the current medical paradigm.

© Billie Harrigan Consulting

Preparing to Birth After Trauma

When preparing to birth after trauma, the pregnant mother will often engage in a number of strategies that might seem excessive to someone who had a positive experience or to the provider who is not trauma-informed (Beck & Watson, 2010; Harrigan, 2017). These strategies can include:

Detailed, extensive, and lengthy birth plans

Hiring a doula

Doing extensive research into providers, locations, routines, and unassisted birth

Avoiding the usual suite of maternity services, such as ultrasound or scheduled prenatal visits

Doing birth art

Writing positive affirmations

Choosing complementary medicine to address health issues

Joining with other parents to learn more about birth, including how to have a breech baby, neonatal resuscitation, pre-eclampsia, etc.

Birth Plans – A Trauma Narrative in Disguise

Lengthy birth plans are generally the client’s attempt at communicating with their care team. It often represents their trauma narrative and is the care provider’s window into their client’s suffering that has brought them to this place. As a form of communication, however, it’s quite ineffective as far too many institutional cultures regard the birth plan as a joke where the longer the birth plan, the sooner she’s booked into the OR for a caesarean. Further, it has no impact on the care provider’s behaviour towards the client and may increase the client’s negative feelings about their birth (Berg, Lundgren, & Lindmark, 2003).

The client-of-trauma is again disadvantaged in trying to garner empathetic care in light of institutional hostility towards various modes of communication, including a birth plan, the use of a doula, self-advocacy, or the inclusion of other advocates. Attempts on the part of the client to change institutional culture are wholly ineffective if the entire facility isn’t addressing entrenched biases (Betrán et al., 2018).

It Begins with an Empathetic Trauma-Informed Care Provider

Photo credit: http://www.thefirsthelloproject.com

Birthing after trauma sometimes feels like a herculean feat for the mother where she is taken on a roller coaster of fear, despair, opposition, obstacles, institutional hostility, ill-equipped care providers, and unfortunately thoughts of suicide.

Yet, there is great hope. As more care providers become trauma-informed and institutions develop appropriate practices to support the client-of-trauma and develop a collaborative and respectful culture, the client can emerge with greater wellness, increased resilience, and growing trust. When a woman has a subsequent birth that fuels her post-traumatic growth, she credits the caring support of her care providers as a crucial element (Beck, 2010)

Nothing compares to the gift of a healing care provider.

Much love,

Mother Billie

References:

Beck, C. T. (2004). Birth trauma: in the eye of the beholder. Nursing Research, 53(1), 28-35.

Beck, C. T., & Watson, S. (2010). Subsequent childbirth after a previous traumatic birth. Nursing research, 59(4), 241-249.

Beck, C. T., Gable, R. K., Sakala, C., & Declercq, E. R. (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder in new mothers: Results from a two‐stage US National Survey. Birth, 38(3), 216-227.

Berg, M., Lundgren, I., Lindmark G. (2003). Childbirth experience in women at risk: Is it improved by a birth plan? Journal of Perinatal Education. 12(2):1–15.

Betrán, A. P., Temmerman, M., Kingdon, C., Mohiddin, A., Opiyo, N., Torloni, M. R., ... & Downe, S. (2018). Interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections in healthy women and babies. The Lancet, 392(10155), 1358-1368.

Bohren, M. A., Hofmeyr, G. J., Sakala, C., Fukuzawa, R. K., & Cuthbert, A. (2017). Continuous support for women during childbirth. The Cochrane Library.

Brady, K. T., Killeen, T. K., Brewerton, T., & Lucerini, S. (2000). Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry,61, 22-32.

Cisternas, P., Salazar, P., Serrano, F. G., Montecinos-Oliva, C., Arredondo, S. B., Varela-Nallar, L., ... & Inestrosa, N. C. (2015). Fructose consumption reduces hippocampal synaptic plasticity underlying cognitive performance. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease,1852(11), 2379-2390.

Cortina, L. M., & Kubiak, S. P. (2006). Gender and posttraumatic stress: sexual violence as an explanation for women's increased risk. Journal of abnormal psychology, 115(4), 753.

Cook, C. A. L., Flick, L. H., Homan, S. M., Campbell, C., McSweeney, M., & Gallagher, M. E. (2004). Posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy: prevalence, risk factors, and treatment. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 103(4), 710-717.

Coxon, K., Homer, C., Bisits, A., Sandall, J., & Bick, D. (2016). Reconceptualising risk in childbirth. Midwifery, 38, 1-5.

Dahlen, H. G., Jackson, M., & Stevens, J. (2011). Homebirth, freebirth and doulas: casualty and consequences of a broken maternity system. Women and Birth, 24(1), 47-50.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) American Psychiatric Assoc Pub; 5 edition(May 22 2013).

Diaz-Tello, F. (2016). Invisible wounds: obstetric violence in the United States. Reproductive Health Matters.

Du, J., Zhu, M., Bao, H., Li, B., Dong, Y., Xiao, C., ... & Vitiello, B. (2016). The role of nutrients in protecting mitochondrial function and neurotransmitter signaling: implications for the treatment of depression, PTSD, and suicidal behaviors. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 56(15), 2560-2578.

Eby, G. A., & Eby, K. L. (2006). Rapid recovery from major depression using magnesium treatment. Medical hypotheses, 67(2), 362-370.

Faravelli, C., Giugni, A., Salvatori, S., & Ricca, V. (2004). Psychopathology after rape. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(8), 1483-1485.

Finlayson, K., & Downe, S. (2013). Why do women not use antenatal services in low-and middle-income countries? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. PLoS medicine, 10(1), e1001373.

Fromm, L., Heath, D. L., Vink, R., & Nimmo, A. J. (2004). Magnesium attenuates post-traumatic depression/anxiety following diffuse traumatic brain injury in rats. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 23(5), 529S-533S.

Gottvall, K., & Waldenström, U. (2002). Does a traumatic birth experience have an impact on future reproduction?. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology,109(3), 254-260.

Harrigan, Billie. (2017). The Epic Failure of the Evidence-Based Movement. https://www.billieharrigan.com/blog/2017/1/16/the-epic-failure-of-the-evidence-based-movement.

Harris, R., & Ayers, S. (2012). What makes labour and birth traumatic? A survey of intrapartum ‘hotspots’. Psychology & Health, 27(10), 1166-1177.

Health Care Consent Act, 1996, S.O. 1996, c. 2, Sched. A

Holten, L., & de Miranda, E. (2016). Women׳s motivations for having unassisted childbirth or high-risk homebirth: An exploration of the literature on ‘birthing outside the system’. Midwifery.

Lev-Wiesel, R., Chen, R., Daphna-Tekoah, S., & Hod, M. (2009). Past traumatic events: are they a risk factor for high-risk pregnancy, delivery complications, and postpartum posttraumatic symptoms?. Journal of Women's Health, 18(1), 119-125.

Matsumura, K., Noguchi, H., Nishi, D., Hamazaki, K., Hamazaki, T., & Matsuoka, Y. J. (2016). Effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on psychophysiological symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in accident survivors: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of affective disorders.

Moyer, C. A., Adongo, P. B., Aborigo, R. A., Hodgson, A., & Engmann, C. M. (2014). ‘They treat you like you are not a human being’: maltreatment during labour and delivery in rural northern Ghana. Midwifery, 30(2), 262-268.

Naiman-Sessions, M., Henley, M. M., & Roth, L. M. (2017). Bearing the Burden of Care: Emotional Burnout Among Maternity Support Workers. In Health and Health Care Concerns Among Women and Racial and Ethnic Minorities (pp. 99-125). Emerald Publishing Limited.

O’Day, Katharine, L, "Outside the System": Motivations and Outcomes of Unassisted Childbirth. Transitions Midwifery Institute, Published online November 19, 2016.

Reed, R., Sharman, R., & Inglis, C. (2017). Women’s descriptions of childbirth trauma relating to care provider actions and interactions. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 17(1), 21.

Roberts, A. L., Austin, S. B., Corliss, H. L., Vandermorris, A. K., & Koenen, K. C. (2010). Pervasive trauma exposure among US sexual orientation minority adults and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Public Health, 100(12), 2433-2441.

Sarandol, A., Sarandol, E., Eker, S. S., Erdinc, S., Vatansever, E., & Kirli, S. (2007). Major depressive disorder is accompanied with oxidative stress: short‐term antidepressant treatment does not alter oxidative–antioxidative systems. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 22(2), 67-73.

Tavares, D., Quevedo, L., Jansen, K., Souza, L., Pinheiro, R., & Silva, R. (2012). Prevalence of suicide risk and comorbidities in postpartum women in Pelotas. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 34(3), 270-276.

United Nations Population Fund. (2004) in: UNFPA (Ed.) State of the World Population 2004. UNFPA, New York.

Vedam, S., Stoll, K., Rubashkin, N., Martin, K., Miller-Vedam, Z., Hayes-Klein, H., & Jolicoeur, G. (2017). The mothers on respect (MOR) index: measuring quality, safety, and human rights in childbirth. SSM-population health, 3, 201-210.

Wu, A., Molteni, R., Ying, Z., & Gomez-Pinilla, F. (2003). A saturated-fat diet aggravates the outcome of traumatic brain injury on hippocampal plasticity and cognitive function by reducing brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuroscience, 119(2), 365-375.

Hocus Pocus - The ARRIVE study says inductions reduce caesareans

In an epic sleight of hand, the US obstetrical industry has managed to produce a study that affirms the “benefits” of universal elective induction of labour at 39 weeks. Headlines have trumpeted this remarkable accomplishment! Inducing labour early “prevents” c-sections!

The conclusion of the much anticipated ARRIVE study are presented in their abstract:

“IOL (induction of labour) in low-risk nulliparous women (first-time mothers) results in a lower frequency of CD (caesarean delivery) without a statistically significant change in the frequency of a composite of adverse perinatal outcomes.”

Obstetricians now have the much-desired go-ahead to routinely induce healthy first-time mothers prior to reaching 40 weeks under the guise that it will reduce c-sections with no additional negative outcomes to the mother or baby.

This is the same outrageous chicanery that brought us the ridiculously executed Term Breech Trial that changed obstetrical practices around the world. It was the excuse the industry was looking for to do what they already wanted to do: surgery.

In an epic sleight of hand, the US obstetrical industry has managed to produce a study that affirms the “benefits” of universal elective induction of labour at 39 weeks. Headlines have trumpeted this remarkable accomplishment! Inducing labour early “prevents” c-sections!

The conclusion of the much anticipated ARRIVE study (Grobman et al., 2018) are presented in their abstract:

“IOL (induction of labour) in low-risk nulliparous women (first-time mothers) results in a lower frequency of CD (caesarean delivery) without a statistically significant change in the frequency of a composite of adverse perinatal outcomes.”

Obstetricians now have the much-desired go-ahead to routinely induce healthy first-time mothers prior to reaching 40 weeks under the guise that it will reduce c-sections with no additional negative outcomes to the mother or baby.

This is the same outrageous chicanery that brought us the ridiculously executed Term Breech Trial that changed obstetrical practices around the world (Hannah et al., 2000). It was the excuse the industry was looking for to do what they already wanted to do: surgery (Hunter, 2013).

Obstetrics is a surgical speciality that also includes attending normal physiologic births. Years ago, the World Health Organisation sought to address disparities in health outcomes around the world in an effort to reduce maternal deaths in vulnerable places. They looked at countries with good outcomes and compared them to countries with poor outcomes. In wealthy nations where infrastructure was in place, food was easily accessible, and infection control measures were widely used, they tended to have a c-section rate around 5%. The WHO initially suggested that a c-section rate of 5-10% across the entire population could improve maternal-fetal outcomes. However, when the c-section rate rose above 15% across a population, the maternal death rate began to rise due to too much surgery.

There was naturally an outcry from the wealthy sector that was safely performing a lot of surgery and the WHO was roundly chastised for trying to prevent them from performing surgery on clients whom they believed would benefit from surgery. So the WHO said a c-section rate of 10-15% was “ideal” as it could potentially save lives, although they’ve subsequently stated that there is no benefit when the rate rises about 10% for a population (Betran, Torloni, et al, 2016).

Caesarean rates by country. (Betran, Ye, et al, 2016)

The problem wasn’t lack of surgery. The problem was that 99% of maternal deaths are in the developing world with half in sub-Sahara Africa and one-third in Southeast Asia where most fatal complications develop during pregnancy and are largely preventable or treatable. Half of these maternal deaths occur in fragile and humanitarian settings such as refugee displacement, natural disasters, and war (WHO, 2018).

Since the WHO’s mistake in encouraging an increase in surgery in impoverished, fragile, and humanitarian settings, the rest of the world’s obstetrics industry has spiraled out of control. Canada’s national c-section rate has risen to 28.2% in 2016-17 (CIHI, 2018) along with an increase in most every other country.

Data from around the world shows an average annual rate of increase in caesarean surgery of 4.4% from 1990 to 2014 (Betran, Ye, et al, 2016). Globally, in 2015 21.1% of all births occur through caesarean surgery, representing just over one in five mothers around the world (Boerma et al., 2018). This rate has risen from 12.1% of all births in 2000, representing a relative increase of 74.38% in just 15 years.

Regionally, caesarean rates are:

Latin America & Caribbean: 44.3% - an absolute increase of 19.4% and a relative increase of 77.91% (from 24.9% to 44.3%)

North America: 32.3% - an absolute increase of 10% and a relative increase of 44.84% (from 22.3% - 32.3%)

Oceania: 32.6% - an absolute increase of 14.1% and a relative increase of 76.22% (from 18.5% to 32.6%)

Europe: 27.3% - an absolute increase of 16.1% and a relative increase of 143.75% (from 11.2% to 27.3%)

Asia: 19.2% - an absolute increase of 15.1% and a relative increase of 343.18% (from 4.4% to 19.5%)

Africa: 7.3% - an absolute increase of 4.5% and a relative increase of 155.17% (from 2.9% to 7.4%)

Global increase in caesarean surgery 1990-2014. (Betran, Ye, et al, 2016)

What’s to blame for these shocking numbers? While it’s common to say it’s due to older, heavier, or more unhealthy mothers, the truth is that caesarean surgery has risen for every clientele group including young, slim, and healthy mothers.

The real increase in surgery comes from:

The management style of the hospital, where proactive management of patient flow and nursing resources results in more surgery and more postpartum haemorrhages (Plough et al., 2017)

Fear of litigation, particularly when malpractice premiums rise about $100,000 (Zwecker, Azoulay, & Abenhaim, 2011)

Financial incentives. Private facilities tend to perform more surgery as their clients have private insurance to pay for it (Dahlen et al., 2012). Even in the Canadian system, where compensation comes from a single payer through universal coverage, when the compensation for surgery is double that of a vaginal delivery, then there is a corresponding 5.6% increase in surgery when all else is equal (Allin, Baker, Isabelle, & Stabile, 2015)

Training, scheduling, and institutional culture drive the rates of surgery in individual institutions (Roth & Henley, 2012)

Both maternal request and maternal morbidity has been blamed for the dramatic increase in surgery, but neither has held up to scrutiny. The increase is physician induced (Roth & Henley, 2012).

Tomasz Kobosz freeimages.com

Now this same industry that has brought us shockingly high rates of surgery due to the nature of the industry says they have a “solution” for this epidemic: induce healthy mothers early.

The caesarean epidemic is due to the industry wanting to perform surgery. The unsupportable conclusions of the Term Breech Trial turned the industry upside-down in a heartbeat and most mothers with a breech-presenting baby are now faced with mandatory surgery. This industry is so invested in getting their way that some of their members have even resorted to using the courts to force clients into non-consenting procedures (Diaz-Tello, 2016).

The idea that inducing a mother early will reduce the incidence of caesarean surgery is akin to saying that if you give a child a pre-dinner snack then they are less likely to over-eat at dinner. Fulfilling the need to medically manage the client’s physiology satisfies the surgeon’s training, preferences, and institutional culture that guide the physician to perform surgery. This is nothing more than a physician placebo. And when this pre-dinner snack doesn’t satisfy any more, and the honeymoon phase of routine early induction wanes, then rates of surgery will rebound.

To begin, an induction is not benign. The risks associated with an induction depend on what is done to the patient. This could involve multiple vaginal exams (infection, sexual re-traumatisation), artificial rupture of membranes (cord prolapse, infection, foetal distress), continuous foetal monitoring (caesarean surgery), chemical cervical ripening (uterine hyperstimulation, uterine rupture, foetal distress, maternal death, foetal death, meconium), IV synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin/syntocinon) (uterine rupture, postpartum haemorrhage, breastfeeding failure, postpartum depression and anxiety, water intoxication leading to convulsions, coma or death, foetal distress, meconium, neonatal jaundice, neonatal brain damage, and neurological dysregulation in the child years later) (Gregory, Anthopolos, Osgood, Grotegut, & Miranda, 2013; Grotegut, Paglia, Johnson, Thames, & James, 2011; Gu et al., 2016; Kurth & Haussmann, 2011; Elkamil et al., 2011).

Inductions are generally more painful and first time mothers are more than 3x more likely to ask for an epidural during an induction (Selo-Ojeme et al., 2011). This leads to a longer labour and pushing stage, need for more synthetic oxytocin, problems passing urine, inability to move after the birth, fever, and more instrumental deliveries (Anim-Somuah, Smyth, Cyna, & Cuthbert, 2018).

Now let’s talk about the study itself.

A total of 3062 women were assigned to labour induction, and 3044 were assigned to expectant management (wait and see approach). Just like with the Term Breech Trial, there was quite a bit of crossover, meaning those who were assigned to the induction group had a spontaneous birth and those who were assigned to a wait-and-see approach were induced (about 5% from each group – 1 in 20 participants). However, the results were reported to the group they were assigned to.

The enrolment was designed to be too small to detect certain outcomes. Adverse outcomes such as maternal death, cardiac arrest, anaesthetic complications, thromboembolism, amniotic fluid embolism, major puerperal infection, or haemorrhage are fairly rare but are associated with both induction and surgery.

Without enough participants, it’s not possible to determine if there was an increase in adverse outcomes from inducing mothers.

Remember, this study took place in the US where they boast some of the worst maternal and neonatal outcomes in the developed world. How they practice obstetrics has much to do with this. Both the induction and the expectant management groups experienced high rates of interventions and the outcomes for the babies were consistent with that:

15% were not breathing at all or were breathing weakly 5 minutes after birth

12% were admitted to the NICU

5% had neonatal jaundice

1% needed breathing support for a day or more

0.7% experienced meconium aspiration syndrome

0.6% had hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy

0.3% suffered intracranial haemorrhage

0.3% had infections

0.2% had seizures

The results for the mothers were equally awful:

5% had severe postpartum haemorrhage of over 1500cc requiring a blood transfusion, blood products, or a hysterectomy

4% suffered a third or fourth degree perineal tear

2% had a postpartum infection

Benjamin Earwicker freeimages.com

With shockingly terrible results like this, the industry has the temerity to suggest that signing up for an elective induction to placate their nerves is a good idea because they’re less likely to perform surgery?

Frankly, it’s asinine nonsense from a group that needs a dramatic change in education and culture. We’ll see how long it takes for this insanity to move throughout the obstetrical world.

Make wise choices, my friends.

Much love,

Mother Billie

References

Allin, S., Baker, M., Isabelle, M., & Stabile, M. (2015). Physician Incentives and the Rise in C-sections: Evidence from Canada (No. w21022). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Anim-Somuah, M., Smyth, R. M., Cyna, A. M., & Cuthbert, A. (2018). Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia for pain management in labour. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 5, CD000331-CD000331.

Betrán, A. P., Torloni, M. R., Zhang, J. J., Gülmezoglu, A. M., WHO Working Group on Caesarean Section, Aleem, H. A., ... & Deneux‐Tharaux, C. (2016). WHO Statement on caesarean section rates. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 123(5), 667-670.

Betrán, A. P., Ye, J., Moller, A. B., Zhang, J., Gülmezoglu, A. M., & Torloni, M. R. (2016). The increasing trend in caesarean section rates: global, regional and national estimates: 1990-2014. PloS one, 11(2), e0148343.

Boerma, T., Ronsmans, C., Melesse, D., Barros, A., Barros, F., Juan, L., Moller, A., Say, L., Hosseinpoor, A., Mu, Y., Neto., D., Temmerman, M. (2018). Global epidemiology and use of and disparities in caesarean section. The Lancet. Volume 392, Issue 10155, P1341-1348, October 12, 2018.

CIHI. Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2018). Hospital Morbidity Database, 2016–2017.

Dahlen, H. G., Tracy, S., Tracy, M., Bisits, A., Brown, C., & Thornton, C. (2012). Rates of obstetric intervention among low-risk women giving birth in private and public hospitals in NSW: a population-based descriptive study. BMJ open, 2(5), e001723.

Diaz-Tello, F. (2016). Invisible wounds: obstetric violence in the United States. Reproductive Health Matters.

Elkamil, A. I., Andersen, G. L., Salvesen, K. Å., Skranes, J., Irgens, L. M., & Vik, T. (2011). Induction of labor and cerebral palsy: a population‐based study in Norway. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica, 90(1), 83-91.

Gommers, J. S., Diederen, M., Wilkinson, C., Turnbull, D., & Mol, B. W. (2017). Risk of maternal, fetal and neonatal complications associated with the use of the transcervical balloon catheter in induction of labour: A systematic review. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 218, 73-84.

Gregory, S. G., Anthopolos, R., Osgood, C. E., Grotegut, C. A., & Miranda, M. L. (2013). Association of autism with induced or augmented childbirth in North Carolina Birth Record (1990-1998) and Education Research (1997-2007) databases. JAMA pediatrics, 167(10), 959-966.

Grotegut, C. A., Paglia, M. J., Johnson, L. N., Thames, B., & James, A. H. (2011). Oxytocin exposure during labor among women with postpartum hemorrhage secondary to uterine atony. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 204(1), 56-e1.

Grobman, W. A., Rice, M. M., Reddy, U. M., Tita, A. T., Silver, R. M., Mallett, G., ... & Rouse, D. J. (2018). Labor induction versus expectant management in low-risk nulliparous women. New England Journal of Medicine, 379(6), 513-523.

Gu, V., Feeley, N., Gold, I., Hayton, B., Robins, S., Mackinnon, A., ... & Zelkowitz, P. (2016). Intrapartum synthetic oxytocin and its effects on maternal well‐being at 2 months postpartum. Birth, 43(1), 28-35.

Hannah, M. E., Hannah, W. J., Hewson, S. A., Hodnett, E. D., Saigal, S., Willan, A. R., & Collaborative, T. B. T. (2000). Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. The Lancet, 356(9239), 1375-1383.

Hunter, B. (2013). Implementing research evidence into practice: some reflections on the challenges. Evidence based midwifery, 11(3), 76-80.

Kurth, L., & Haussmann, R. (2011). Perinatal Pitocin as an early ADHD biomarker: neurodevelopmental risk?. Journal of attention disorders, 15(5), 423-431.

Linton, A., Peterson, M. R., & Williams, T. V. (2004). Effects of maternal characteristics on cesarean delivery rates among US Department of Defense healthcare beneficiaries, 1996–2002. Birth, 31(1), 3-11.

Plough, A. C., Galvin, G., Li, Z., Lipsitz, S. R., Alidina, S., Henrich, N. J., ... & McDonald, R. (2017). Relationship between labor and delivery unit management practices and maternal outcomes. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 130(2), 358-365.

Roth, L. M., & Henley, M. M. (2012). Unequal motherhood: racial-ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in cesarean sections in the United States. Social Problems, 59(2), 207-227.

Selo-Ojeme, D., Rogers, C., Mohanty, A., Zaidi, N., Villar, R., & Shangaris, P. (2011). Is induced labour in the nullipara associated with more maternal and perinatal morbidity?. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics, 284(2), 337-341.

Washington, S., Caughey, A. B., Cheng, Y. W., & Bryant, A. S. (2012). Racial and ethnic differences in indication for primary cesarean delivery at term: experience at one US Institution. Birth, 39(2), 128-134.

WHO, World Health Organization. (2018). Fact Sheet-Maternal Mortality.

Zwecker, P., Azoulay, L., & Abenhaim, H. A. (2011). Effect of fear of litigation on obstetric care: a nationwide analysis on obstetric practice. American journal of perinatology, 28(04), 277-284.